When Clinical Algorithms Don’t See Us. Māori Data Sovereignty Approaches to Detecting and Mitigating Bias in Health AI

The rapid adoption of artificial intelligence (AI) and algorithmic decision support in health systems is unfolding within long standing patterns of inequity for Indigenous peoples. In Aotearoa New Zealand, Māori already experience systematic barriers to care, racism, and poorer health outcomes across almost every major condition (Came et al., 2020; Espiner et al., 2021). Without deliberate safeguards, clinical algorithms risk reproducing and amplifying these inequities in opaque ways. International evidence demonstrates how health AI systems can encode structural racism, including widely used risk prediction tools that systematically under estimate the needs of racialised populations (Celi et al., 2022; Obermeyer et al., 2019; Vyas et al., 2020). Emerging New Zealand research likewise shows that biases in electronic health record (EHR) data and modelling choices can disadvantage Māori when AI is applied to local health data (Joseph, 2025; Yogarajan et al., 2022).

This paper argues that Māori Data Sovereignty, alongside a developing Māori focused approach to algorithmic sovereignty, provides a necessary foundation for detecting and mitigating algorithmic bias in health AI. Indigenous Data Sovereignty scholarship conceptualises data as relational and governed by collective rights, and cautions that AI can intensify colonial extraction and control where those rights are ignored. We situate algorithmic bias within the context of Te Tiriti o Waitangi breaches in health and persistent Māori health inequities, drawing on the Waitangi Tribunal’s WAI 2575 findings and contemporary Māori health research (Came et al., 2020; Espiner et al., 2021; Waitangi Tribunal, 2019). We then synthesise international evidence on algorithmic bias in clinical decision making, before outlining how Māori Data Sovereignty reframes “fairness” in AI from a Māori perspective.

We propose a Māori Data Sovereignty aligned framework for detecting bias through tikanga aligned algorithmic audits, Māori led stratified performance analyses, and equity focused evaluation metrics; and for mitigating bias through structural changes in data governance, model objectives, procurement, and oversight that embed Māori authority and values. Hypothetical vignettes illustrate potential harms and remediation strategies in common clinical applications such as risk stratification, triage, and readmission prediction. Finally, we reflect on implications for European and other international health systems seeking to align health AI with the rights of Indigenous and minoritised peoples. Rather than treating algorithmic bias as a purely technical problem, Māori Data Sovereignty insists that detection and mitigation are inseparable from decolonising health systems and honouring Indigenous self determination.

Keywords: Māori Data Sovereignty; algorithmic bias; clinical decision support; health AI; Indigenous health; Te Tiriti o Waitangi

Introduction

Health systems globally are investing heavily in AI enabled tools for diagnosis, risk prediction, triage, resource allocation, and population health management. These systems are often promoted as objective, efficient, and capable of removing human bias from clinical decision making. Yet a growing body of evidence shows that AI in healthcare can reproduce, conceal, and intensify existing inequities, particularly for racialised and Indigenous populations (Celi et al., 2022; Vyas et al., 2020).

In Aotearoa New Zealand, this technological shift is occurring in a context where Māori, the Indigenous people of the country, experience entrenched inequities in health outcomes and access to care. Māori face practical barriers, hostile care environments, and racism that shape whether and how they reach hospital services (Espiner et al., 2021). The Waitangi Tribunal’s WAI 2575 Hauora report found that the Crown had breached Te Tiriti o Waitangi by failing to design and administer primary health care to actively address Māori health inequities, and by failing to give effect to tino rangatiratanga (Māori authority) in health governance (Came et al., 2020; Waitangi Tribunal, 2019). These structural breaches form the substrate upon which new AI systems are being built.

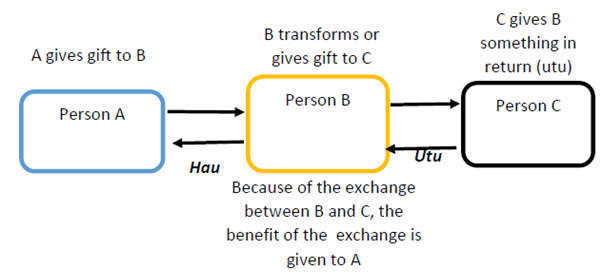

Internationally, Indigenous Data Sovereignty scholarship highlights how data and AI can become new frontiers of extraction and control if Indigenous rights and governance are not centred (Carroll et al.). Within Aotearoa, Māori Data Sovereignty provides a specific articulation of these ideas, treating Māori data as taonga (treasures) subject to collective rights and tikanga based governance. Building on this, Māori led digital governance work increasingly extends sovereignty thinking into the algorithmic domain by insisting that Māori authority applies across the full AI lifecycle: problem framing, data access and linkage, model development and evaluation, deployment settings, monitoring, audit, and redress.

This paper brings these strands together to ask when clinical algorithms “do not see” Māori through under representation, misclassification, or harmful optimisation and how can Māori Data Sovereignty be operationalised to detect and mitigate algorithmic bias in health AI? We proceed in four steps. First, we contextualise algorithmic bias within Māori health inequities, Te Tiriti breaches, and digital governance debates. Second, we synthesise evidence on algorithmic bias in health AI, drawing on international and New Zealand research. Thirdly, we outline Māori Data Sovereignty aligned approaches to detecting and auditing bias in clinical algorithms. Finally, we propose Māori Data Sovereignty aligned mitigation strategies that reconfigure data governance, model design, procurement, and oversight to uphold Māori rights and wellbeing. While grounded in the Māori context, the analysis offers insights for other Indigenous and minoritised populations and for European health systems grappling with similar challenges.

Algorithmic bias in clinical decision making

Forms of bias in health AI

Health AI systems can embody multiple, overlapping forms of bias. Data bias arises when groups are under represented in training data, when data quality differs systematically across populations, or when measurement practices vary by setting or group. Label and target bias occurs when the outcomes used for training such as cost, hospitalisation, or non attendance reflect structural inequities and system constraints rather than underlying clinical need. Model bias can be introduced through design choices about features, loss functions, and trade offs, including optimisation for overall accuracy that sacrifices performance for smaller groups. Deployment bias emerges when implementation context shapes outcomes, for example when clinicians over rely on algorithm outputs, access to AI enabled services is uneven, or feedback loops reinforce existing inequities.

Global reviews document how these dynamics perpetuate and exacerbate health disparities (Celi et al., 2022). Obermeyer et al. (2019), for example, showed that a widely used United States population health algorithm used healthcare cost as a proxy for need and systematically underestimated the care needs of Black patients because structural racism had historically suppressed spending on their care. Vyas et al. (2020) also catalogue a range of race corrected clinical algorithms from kidney function estimation to obstetric risk calculators that embed race variables in ways that can delay or deny care for racialised groups. These examples underline that algorithmic bias is not a rare technical glitch; it is a predictable outcome when AI is layered onto inequitable systems.

New Zealand evidence on algorithmic bias in health data

New Zealand specific research suggests similar dynamics are present in local health datasets. Yogarajan et al. (2022) analysed large EHR datasets from New Zealand hospitals and general practices and identified ethnic differences in data completeness, concept representation, and model performance. They also show how fairness metrics such as disparate impact, equal opportunity, and equalised odds can reveal inequities that are invisible when models are judged only by aggregate accuracy. Joseph (2025) likewise argues that public health algorithms, if trained on historically biased data without equity anchored design, can silently entrench inequitable resource allocation and surveillance. Together, these studies indicate that data and model bias are not hypothetical risks for Māori; they are practical concerns for any health AI deployment in Aotearoa.

Māori health inequities, Te Tiriti o Waitangi, and digital health

Māori health inequities are profound, persistent, and well documented. Māori experience higher rates of chronic disease, shorter life expectancy, and worse outcomes across most major conditions compared with non Māori (Came et al., 2020; Espiner et al., 2021). Barriers to access include cost, transport, appointment systems, racism, poor communication, and culturally unsafe environments, as highlighted in Espiner et al.’s (2021) review of Māori access to hospital services.

The Waitangi Tribunal’s WAI 2575 Hauora report found that the Crown had systematically breached Te Tiriti o Waitangi in health by failing to design and fund primary health care to achieve equity, failing to target and track funding intended for Māori health, and failing to ensure Māori decision making authority in health system design and governance (Came et al., 2020; Waitangi Tribunal, 2019). The Tribunal recommended Tiriti compliant legislation and policy, strengthened accountability, investment in Māori health, and recognition of extant Māori political authority, including consideration of an independent Māori health authority.

Digital health and AI can either reinforce or disrupt these patterns. Māori Data Sovereignty scholarship emphasises that, in a context of historical breaches and ongoing structural racism, digitisation and datafication without Māori governance can deepen Crown control and commercial exploitation of Māori data. Automated systems are embedded in wider structures of state power, and that data and algorithms cannot be separated from the systems within which they operate. Health AI must therefore be assessed not only for technical performance, but also for whether it advances or undermines Te Tiriti obligations and Māori self determination.

Māori Data Sovereignty and Māori focused algorithmic sovereignty

Extending sovereignty into the algorithmic domain

A Māori focused approach to algorithmic sovereignty extends Māori Data Sovereignty from data into the design, deployment, and governance of algorithms themselves. In practical terms, this means Māori authority across the full AI lifecycle: deciding whether a use case should exist, setting the objectives and definitions of harm, controlling data access and linkage, determining evaluation criteria (including equity thresholds), shaping deployment contexts and consent settings, and maintaining ongoing monitoring, audit, and redress mechanisms. This approach aligns with broader Indigenous and international work that warns AI and big data can replicate colonial harms if Indigenous data sovereignty is ignored, while also recognising that Indigenous led governance can re orient AI development towards Indigenous futures.

When clinical algorithms don’t see us: Pathways of harm for Māori

The phrase “when clinical algorithms don’t see us” captures several interlocking patterns. Māori may be effectively invisible when they are absent or under represented in training datasets, producing models tuned primarily for non Māori populations. Māori may also be mis recognised: present in data but misclassified, miscoded, or incompletely recorded (including ethnicity mis recording), or measured using constructs that do not reflect Māori realities. Harm also arises when models encode deficit framing, treating Māori culture, whānau structures, or socioeconomic conditions as risk factors without accounting for structural racism and historical dispossession. Finally, models can be optimised against Māori interests when they prioritise aggregate efficiency or cost saving, even where this worsens Māori outcomes, echoing concerns raised in international studies of cost based risk algorithms (Celi et al., 2022; Obermeyer et al., 2019).

Consider a hypothetical hospital wide risk stratification tool designed to identify patients at high risk of unplanned readmission within 30 days. If it uses prior cost or utilisation as a proxy for need, is trained on historical data where Māori have been less likely to access certain services due to racism and structural barriers, and is evaluated on overall accuracy without stratification by ethnicity, it is likely to under identify Māori patients who would benefit from additional support and to over prioritise non Māori. This is algorithmic bias rooted not only in data, but in the wider pattern of Te Tiriti breaches and underfunding documented by WAI 2575 (Waitangi Tribunal, 2019).

A similar risk arises with AI assisted triage tools trained on clinical notes. If models absorb and reproduce patterns of racially coded language and implicit clinician bias through text representations, they can legitimise and amplify under triage or delayed care for Māori (Celi et al., 2022; Yogarajan et al., 2022). Without Māori governance, such tools can turn historically contingent bias into apparently neutral evidence.

Māori Data Sovereignty approaches to detecting algorithmic bias

Detecting bias through Māori Data Sovereignty lens requires more than applying generic fairness metrics. It reframes what counts as performance, who defines harm, and how evidence of bias is interpreted and acted upon.

Māori led algorithmic governance and audit

Māori Data Sovereignty implies that Māori collectives must hold meaningful authority over how algorithms that materially affect Māori health are designed, evaluated, governed, and where required decommissioned. In practice, this can include Māori governance bodies with decision making power over adoption and ongoing use of health algorithms; co designed algorithmic impact assessments that explicitly address Te Tiriti obligations, Māori rights, and tikanga aligned audit processes and robust equity assessment protocols with Māori participation.

Ethnicity and iwi stratified performance analysis

From a Māori Data Sovereignty perspective, algorithms affecting Māori cannot be evaluated solely on population level metrics. At minimum, evaluation should include stratified performance by ethnicity and where governance arrangements permit by Māori collectives, with explicit attention to false negatives and false positives, calibration, and error types. This matters because, in many clinical contexts, false negatives for Māori (missed diagnoses, under estimated risk, failure to trigger support) can have especially severe consequences. Intersectional evaluation is also important for example, Māori women, Māori with disabilities, or Māori living in rural areas, because algorithmic harms often concentrate where multiple forms of marginalisation overlap. Yogarajan et al. (2022) demonstrate how fairness metrics can surface differential performance across ethnic groups in New Zealand models; Māori Data Sovereignty extends this by insisting Māori help define acceptable thresholds and trade offs considering Māori health aspirations and rights.

Scrutinising targets, labels, and proxies

Māori Data Sovereignty requires scrutiny of what algorithms are trained to predict. Many common targets such as cost, length of stay, did not attend, or historical utilisation may reflect system behaviour and constraints rather than clinical need, and they may embed discriminatory patterns. Labels may also carry bias where diagnostic codes are applied differently by ethnicity, or where clinician judgement has been shaped by structural racism. Proxy variables such as deprivation indices can inadvertently stand in for colonially produced inequities, including historical dispossession. The Obermeyer et al. (2019) example illustrates the risk of using cost as a proxy for need; a Māori Data Sovereignty aligned approach demands explicit justification of targets and, where necessary, redesign so that model objectives align with Māori defined notions of need, hauora, and collective wellbeing.

Community centred evidence of harm

A Māori Data Sovereignty aligned approach also values whānau and community testimony about how algorithms are experienced in practice, such as repeated de prioritisation, being labelled “non compliant,” or erosion of trust. It requires accessible pathways for Māori patients, whānau, and Māori providers to raise concerns and trigger audits, with clear accountability for follow up. It also recognises that harms may be relational and cultural (including breaches of tikanga and damage to trust) as well as clinical. This aligns with Indigenous critiques that warn health data for AI can reproduce extractive dynamics unless community defined harms and benefits remain central.

Māori Data Sovereignty approaches to mitigating algorithmic bias

Detecting bias is only the first step. Māori Data Sovereignty points towards structural mitigation strategies that reshape how health AI is conceived, built, and governed.

Re designing data infrastructures under Māori governance

Mitigation begins upstream with data governance and infrastructure. This can involve Māori governed data environments for health AI in which Māori collectives hold authority over access, linkage, and re use of Māori health data, potentially through dedicated Māori data trusts or governance entities. It also requires embedding tikanga based conditions into data sharing agreements to prevent repurposing beyond agreed purposes or without consent. Strengthening Māori led data quality initiatives is critical, including accurate ethnicity (and where appropriate iwi) recording, culturally appropriate coding, and the inclusion of Māori defined indicators of wellbeing. Existing Māori digital governance work provides practical direction for operationalising governance across data lifecycles.

Re setting optimisation goals and fairness constraints

From a Māori Data Sovereignty standpoint, algorithms should be explicitly designed to reduce inequity and meet Te Tiriti obligations, not merely maximise predictive accuracy or cost effectiveness. This can include equity weighted objectives that penalise harmful errors for Māori more heavily, fairness constraints chosen through Māori led governance processes, and scenario testing focused on downstream Māori outcomes rather than only system wide averages. Technical methods exist for these approaches, but Māori Data Sovereignty clarifies that the right fairness definition is not universal; it must be grounded in Māori values, rights, and health aspirations.

Tikanga aligned co design and procurement

Mitigation also depends on how AI systems enter health organisations. Tikanga aligned co design means involving Māori clinicians, Māori data experts, and communities from the earliest stages, including deciding whether an AI intervention is appropriate at all. Procurement processes should then hard wire sovereignty requirements: Māori governance roles, transparency expectations, explainability, equity evaluation obligations, and clear restrictions on secondary use. Contracts can require audit rights, contestability, and documentation sufficient to enable independent evaluation.

Continuous monitoring, redress, and decommissioning

Because algorithms operate in dynamic systems, mitigation must be ongoing. This includes routine equity monitoring with results reported to Māori governance bodies, clear redress pathways for whānau when harm is identified, and the ability to pause or decommission tools that conflict with Te Tiriti obligations or entrench inequity. This also implies that algorithm governance cannot be separated from broader decolonising health reforms; where the system remains inequitable, AI can harden rather than fix those inequities (Came et al., 2020; Vyas et al., 2020).

Implications beyond Aotearoa and for Euro centric health systems

Although grounded in the Māori context, these arguments extend to Indigenous peoples globally and to health systems serving minoritised communities. AI and big data risk becoming new mechanisms of colonial control when developed without Indigenous data sovereignty, but they can be re oriented to support Indigenous futures when governed by Indigenous values and authority.

Euro centric health systems are increasingly adopting AI for triage, imaging analysis, risk prediction, and resource allocation, often in contexts shaped by histories of racism and medical harm for Indigenous and minoritised groups. The Māori experience suggests three transferable lessons: algorithmic bias should be addressed as structural rather than purely technical; communities require sovereignty and enforceable authority rather than consultation alone; and fairness and trustworthiness must be grounded in local histories, legal obligations, and community aspirations rather than imported wholesale. For a European Society of Medicine audience, Māori Data Sovereignty provides a concrete example of Indigenous-led governance reshaping what trustworthy health AI must mean in practice.

Conclusion

Clinical algorithms that do not see Māori through invisibility, misrecognition, or harmful optimisation are not inevitable, but they are predictable when AI is built on colonially structured data and inequitable health systems. International evidence shows health AI can encode and amplify racial bias (Celi et al., 2022; Obermeyer et al., 2019; Vyas et al., 2020), and New Zealand research indicates that local data and likely applications are subject to similar risks (Joseph, 2025; Yogarajan et al., 2022).

Māori Data Sovereignty offers a foundation for both detection and mitigation by reframing data and algorithms as taonga governed by collective rights and tikanga, insisting on Māori authority across the AI lifecycle, and orienting algorithmic performance towards equity and Te Tiriti compliance rather than narrow efficiency. For Aotearoa and beyond, taking these commitments seriously requires shifting from ad hoc technical fixes to structural, Māori led governance of health AI; embedding Indigenous authority in design, evaluation, and oversight; integrating community testimony with technical metrics; and recognising that truly “seeing” Indigenous peoples in health AI requires confronting and transforming the systems within which these tools operate.

References

Came, H., O’Sullivan, D., Kidd, J., & McCreanor, T. (2020). The Waitangi Tribunal’s WAI 2575 report: Implications for decolonizing health systems. Health and Human Rights Journal, 22(1), 209–220.

Celi, L. A., Cellini, J., Charpignon, M.L., Dee, E. C., Dernoncourt, F., Eber, R., Mitchell, W. G., Rahman, M. H., Salciccioli, J. D., Saberian, P., & Marshall, D. C. (2022). Sources of bias in artificial intelligence that perpetuate healthcare disparities—A global review. PLOS Digital Health, 1(3), e0000022.

Espiner, E., Paine, S.J., Weston, M., & Curtis, E. (2021). Barriers and facilitators for Māori in accessing hospital services in Aotearoa New Zealand. New Zealand Medical Journal, 134(1546), 47–58.

Joseph, J. (2025). Algorithmic bias in public health AI: A silent threat to equity in low resource settings. Journal of Public Health Policy, 46(2), 123–138.

Obermeyer, Z., Powers, B., Vogeli, C., & Mullainathan, S. (2019). Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science, 366(6464), 447–453.

Vyas, D. A., Eisenstein, L. G., & Jones, D. S. (2020). Hidden in plain sight—Reconsidering the use of race correction in clinical algorithms. New England Journal of Medicine, 383(9), 874–882.

Waitangi Tribunal. (2019). Hauora: Report on Stage One of the Health Services and Outcomes Kaupapa Inquiry (WAI 2575). Waitangi Tribunal.

Yogarajan, V., Dobbie, G., Leitch, S., Keegan, T. T., Bensemann, J., Witbrock, M., Asrani, V., & Reith, D. (2022). Data and model bias in artificial intelligence for healthcare applications in New Zealand. Frontiers in Computer Science, 4, 1070493.