This is an extraction of Chapter 8 from Tikanga Tawhito: Tikanga Hou Kaitiaki Guidelines for DNA Research, Storage and Seed Banks with Taonga Materials.

9 Specific Tikanga Associated DNA and other biological samples

The following two primary sources of research have been used to identify appropriate tikanga with Māori genetic Data research: Royal Commission on Genetic modification and the International Research Institute for Māori and Indigenous Education (IRI) based at Auckland University. Māori interviewees for this research also concurred that these are the primary tikanga with gene research.

The public consultation and submissions from the Royal Commission on Genetic modification (RCGM) in 2000 involved a number of meetings around the country and public submissions (Eichelbaum, 2001). The Commission heard from over 400 experts, including scientists, environmentalists, and ethical specialists. It considered more than 10,000 public submissions and heard the view of many others during a series of public meetings, hui, and workshops around New Zealand. The following seven tikanga were identified: Hau, Kaitiaki, Mākutu, Mauri, Rangatiratanga, Wairua and Whakapapa.

The feedback recorded by the Commission is consistent with other research findings (Beaton et al., 2017); (Hudson, Southey, et al., 2016); (Hutchings, 2004a); (Mead, 1996); (Mead, 1998); (Mead, 2016b); (Waitangi Tribunal, 2003a); (Pihama et al., 2015).

The secondary research was conducted by the International Research Institute for Māori and Indigenous Education (IRI) based at Auckland University. They produced a report entitled Māori and Genetic Engineering (Cram et al., 2000). The report explored three key areas (food, human health, and biological diversity). This research was conducted with twenty-four key informant interviews with Māori who were knowledgeable about tikanga Māori and/or GE and related issues as well as nineteen general focus groups with a total of ninety-four Māori from a variety of locations, age brackets and backgrounds.

In total there were eight primary tikanga and cultural concerns identified and explained in depth below. There are seven other identified tikanga Māori concerns that are widely shared with other Indigenous Peoples regarding DNA and genomic research:

- “Breaches of culture.

- Use of Indigenous knowledge to create new biotechnological inventions:

- Lack of consultation with Indigenous Peoples:

- Lack of benefits to Māori people:

- Inability of Intellectual Property Laws to protect Māori and their traditional knowledge:

- Loss of control of traditional knowledge:

- Commercialisation of genetic materials” (Hutchings, 2004b).

Hau

The primary tikanga that impacts the donor, and the recipient is called “Hau”. Hau is the vitality or vital essence of a person, place, or object. Any gift or thing that is given, has the donor’s hau as a part of that gift. Respecting Hau as a tikanga ensures the physical, mental, and spiritual wellbeing of the donor person is respected and protected. It covers a wide range of circumstances with gene research and also aligns with Te Whare Tapa Whā (Durie, 1984).

Hau is also used when returning a present in acknowledgement for a present received (Benton et al., 2013). In New Zealand, regarding human gene samples; The Code of Health and Disability Services Consumers’ Rights: Health and Disability Commissioner (Code of Health and Disability Services Consumers’ Rights) Regulations 1996: Right 6, The right to be fully informed and Right 7 “The right to make an informed choice and give informed consent is one way to start the process of recognising the hau of the donor”.

When a DNA sample is taken from a Taonga Species, there must be some reciprocal arrangement with the donor or the kaitiaki of the DNA sample.

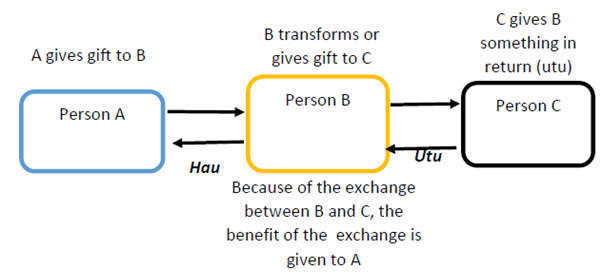

The following diagram created provides an illustration of how hau operates.

Hau (Payne, D. 2020)

Kaitiakitanga

Kaitiakitanga is defined in the Resource Management Act as guardianship and/or stewardship. Marsden and Royal (2003) state “Stewardship is not an appropriate definition since the original English meaning of Stewardship is ‘to guard someone else’s property’. Apart from having overtones of a master-servant relationship, ownership of property in the pre-contact period was a foreign concept. The closest idea to ownership was that of the private use of a limited number of personal things such as garments, combs, and weapons. Apart from this, all other use of land, waters, forests, fisheries were a communal and or Iwi right. All-natural resources, all life was birthed from Papatūānuku. Thus, the resources of the earth did not belong to man, but rather man belonged to the earth. Kaitiakitanga and Rangatiratanga are intimately linked”.

In recent times, kaitiaki has become a common term used by bureaucrats in environmental policies and in legislation. Upoko of Ngāi Tahu Rūnanga Ngāi Tūāhuriri states that “Kaitiaki is a term used with such irregularity that it is now meaningless. Today, kaitiaki is a term used by Māori and Pākehā bureaucrats as a gap-filler to mean everything and yet nothing” (Tau, 2017, p. 15).

Benton (2013) states that the modern usage of the word has come to encapsulate an emerging ethic of guardianship or trusteeship especially over natural resources, “Kaitiaki are left behind by deceased ancestors to watch over their descendants and to protect sacred places. Kaitiaki are also messengers and a means of communication between the spirit realm and the human world. Kaitiaki can be in the form of birds, insects, animals, and fish. Many kaumātua act as guardians of the sea, rivers, lands, forests, family, and marae” (Barlow, 1991, p. 41).

The term tiaki, whilst its basic meaning is ‘to guard’ has other closely related meanings depending on the context. Tiaki may therefore also mean, to keep, to preserve, to conserve, to foster, to protect, to shelter, to keep watch over. The prefix kai with a verb denotes the agent of the act. A kaitiaki is a guardian, keeper, preserver, conservator, foster-parent, protector. The suffix tanga, when added to the noun, transforms the term to mean guardianship, preservation, conservation, fostering, protecting, sheltering.

Each generation has an inherited obligation to act as kaitiaki for the genetic data they have and for their whānau genetic data in addition to other Taonga Species.

Karakia

Karakia act as intermediary between the spiritual world and the temporal world (Rewi, 2010a, p. 138). Karakia plays just as an important role in Māori genetic data research as karakia plays in any other aspect of Māori life. Māori “guarded their well-being by observing tikanga, that is, by observing tapu, and by karakia and rituals which were strictly adhered to lest the hapless practitioner be punished by the deity to whom he had appealed” (Buck, 1949, pp. 489-504).

“Karakia is first mentioned in the story of Ranginui and Papatūānuku. Te Rangikaheke’s version of the story tells how Tūmatauenga was given his karakia after he had overcome his brothers, all except Tāwhiri. He was given his karakia as the means by which he would be able to overcome his elder brothers and use them for food. And so Tāwhirimatea elder brothers were made noa and his karakia were sorted out, the particular karakia for Tāne Māhuta, those for Tangaroa, those for Rongo-mā-Tāne, those for Haumia, those for Tūmatauenga. Tāwhirimatea sorted out these karakia so that his elder brothers might be turned back to him to be his food. There is another karakia for Papatūānuku, which renders free from restriction all that is sought by her. And there is ritual for human beings” (Shirres, 1986).

In another text, Te Rangikaheke says that our karakia come down to us from the time of the separation of Ranginui and Papatūānuku and he names different types of karakia. “It is the same power of the word given to Tū, which is given to us. Then Rangi and Papa were separated. People had become many, there in the darkness. It was from that time that life-giving chants, chants for childbirth, chants for the weather, for sickness, for food, for possessions, and for war, came down to us” (Shirres, 1986).

Karakia often call on the atua and are a means of participation, of becoming one, with the atua and the ancestors and with events of the past in the ‘eternal present’ of ritual. Karakia speak the words of the ancestors and are the work of a people, rather than an individual. “Karakia consists of pleas, prayers and incantations addressed to the gods who reside in the spirit world. Karakia are offered so the gods may intercede in the affairs of mortal men by providing comfort, guidance, direction, and blessings for them in their various activities and pursuits. Some prayers have special ritual functions, while others are used for protection, purification, ordination, and cleansing. Karakia are generally used to ensure a favourable outcome to important events and undertakings and can be used for every aspect of life. Karakia call upon many of our Atua for direction” (Barlow, 1991).

Māori karakia whenever there is a special occasion or something tapu is involved, especially with repatriation of human remains, whakapapa and other tapu objects. Taking a genetic sample, whether from saliva, blood, hair etc., or from the surface of a foreign object, a karakia is required to acknowledge the tapu, mauri, whakapapa and wairua of the species and the associated atua.

Mākutu

Mākutu is both the process of injuring a person or a living entity by sorcery, and the spell or incantation directed at harming an individual or group, a natural consequence of theft or breach of tikanga (Richard Benton et al., 2013, p. 150). There are a number of sources that reference unexplained bad luck or the tikanga of mākutu that occurred after breaking tikanga (Mahuika, 2015); (O’Biso, 1999); (Stirling & Salmond, 1985).

One of the most common forms of mākutu is that in which a medium is used in order to connect the spells of the tohunga with the object to be acted upon by them. This medium, termed ‘ohonga’ and ‘hohonga’, “when it is the object, is usually a fragment of a person’s clothing, a lock of hair, a portion of spittle, or a portion of earth on which he has left his footprint” (Best, 1901, p. 75). Tipuna Māori (Māori ancestors) also considered knowledge to be tapu. As Māori genetic data contains vast amounts of genealogical knowledge, DNA must also be considered tapu.

Breaching tikanga and suffering the consequences are a widely held beliefs among many Iwi and individuals, though not so relevant in modern day society, as much of the tapu has been lifted and the mauri of the natural world dead. But the risk of mākutu is still relevant. Though it may or may not be a spiritual consequence, issues such as bio piracy and Intellectual Property Rights are the modern-day equivalent of mākutu.

As it is becoming more common to provide a saliva test to send to an overseas company who will then identify your ancestry through DNA, the risk of mākutu is very high. Especially considering the sacred whakapapa is being shipped overseas and stored by international staff who have no awareness of tikanga. Considerations of how and where Māori genetic data is stored is essential to ensuring the health and wellbeing of Taonga Species is maintained.

Mauri

Traditional knowledge states that every natural object and living thing has a spiritual aspect called a mauri. If we sit down, our mauri sits down with us and some mauri can be left behind if not considered. Likewise, a photograph of a person contains the mauri of the person. Hence, photos of the dead are tapu. Yet, Māori genetic data is stored somewhere overseas in a laboratory among many other bodily fluids from many other cultures and religions with the DNA from the living and dead.

Māori genetic data is no different. The mauri associated with the Taonga Species is a part of the data and must be treated as sacred. Therefore, any Māori genetic data sample that is stored, manipulated, and anonymised will still contain the mauri of the person in the same manner as a photo.

In te ao Māori, information is tapu and contains the tapu of the person it is about. DNA contains the mauri of not only the individual that the DNA was sourced from, but from their entire genealogical lines of descent.

John Rangihau explains the process of gathering and learning new information “I talk about mauri and some people talk about tapu. Perhaps the words are interchangeable. If you apply this life force to all things – inanimate and animate – and to concepts, and give each concept a life of its own, you can see how difficult it appears for older people to be willing and available to give out information. They believe it’s a part of them, part of their own life force, and whey they depart they are able to pass this whole thing through and give it a continuing character. Just as they are proud of being able to trace their genealogy backwards, in the same way they can continue to send the mauri of certain things forward” (King, 1978).

“Once you learn new knowledge it becomes a part of your mauri” (King, 1978). Hence knowledge was not always provided and could not be provided. Because of this, Indigenous knowledge and artefacts have been taken without permission by researchers and governments without permission.

Rangatiratanga

According to Barlow, this is a new term coined by Pākehā “when the Treaty of Waitangi was written, and the land was colonised. But in recent times, some unschooled Māori have widely adopted the term tino rangatiratanga to epitomize their sovereign powers instead of using the correct term arikitanga” (Barlow, 1991, p. 131). Nevertheless, it is widely understood to be Māori sovereignty. The attributes of Rangatiratanga are possessing authority and being able to act authoritatively, along with nobility, mind and conduct (Benton et al., 2013, p. 325).

This tikanga recognises that the inalienable rights that Māori have with DNA from Taonga Species is essential.

Wairua

Wairua was used in relation to elements such as mauri, whakapapa, karakia and whanaungatanga.

The heavy influence of Christianity has seen the word wairua adopted to be more appeasing to Christianity. The term wairua was adopted in biblical translations to cover terms translated in English as ‘soul’ and ‘spirit (Ballara, 1998); (Benton et al., 2013). At its core, wairua refers to the spirit of a person as distinct from both the body and the mauri “The integrating force of life is the wairua; wairua envelopes the heart, liver, lungs, kidneys, intestines, blood, muscles, ears, it is the cultivator, caretaker, and integrator of all these things, so they stay in that place, within the part of the body. The wairua and its properties are also revered because they are the cause of man’s sanctity; if the wairua did not disengage itself, man would not die; and if every part (of the body) that was cleansed of tapu was held onto by the wairua, life would not end” (Benton et al., 2013).

“At its core, wairua refers to the spirit of a person as distinct from both the body and the mauri” (Benton et al., 2013). Wairua lives in and is a part of a DNA. Therefore, once DNA has been taken, that person or other species wairua has also been taken and is stored in a foreign system. Not until the species with which the DNA was taken is dead, will the wairua also die, but the mauri will remain.

Wairua is a fundamental aspect of any genetic Māori data that must be recognised and respected.

Whakapapa

“In its simplest sense whakapapa is genealogy, in a wider sense whakapapa attempts to impose a relationship between an iwi and the natural world. For Māori, “the world was ordered and understood by whakapapa and is the skeletal structure to Māori epistemology” (Te Maire. Tau, 2001). Moreover, whakapapa is “a metaphysical framework constructed to place oneself within the world” (Tau, 2003). It is one of the most prized forms of knowledge and great efforts are made to preserve it (Barlow, 1991, p. 174) & (Gibbons 2002, p. 7). Whakapapa was the central principle that ordered the universe (Salmond, 2017, p. 42). Whakapapa can be interpreted literally as ‘the process of layering one thing upon another’ (Ngata 2011, p. 6). In a wider sense whakapapa attempts to impose a relationship between an iwi and the natural world. Moreover, whakapapa is a metaphysical framework constructed to place oneself within the world (Tau, 2003). Joe Te Rito has written that whakapapa grounds him ‘firmly in place and time’, and connects us to the past in ways that confirm our identity as Māori through a deep sense of ‘being’ (Te Rito, 2007, p. 9).

“In research, whakapapa has been presented in tribal histories, Māori Land Court records, and consistently as a framework for mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge) and Māori research methodologies” (Mahuika, 2019). “Whakapapa is a research methodology or tool apt in the analysis of natural ‘phenomena’, origins, connections and relationships, and even predicting the future” (Te Ahukaramū Charles. Royal, 1992, pp. 6-8).

Whakapapa has always been considered the explanatory framework for the world and everything in it. Whakapapa chronicled evolutions from the beginning of time and explained Māori social and political organisation to each other and the natural and spiritual world. Whakapapa as an approach, whether it be relevant to genetics, history, education, or elsewhere, is inextricably connected to underlying protocols and tribal ethics. “Whakapapa has its own tribal specific, and collective Māori, politics that seek out connections and inclusivity and are necessarily exclusive when it comes to exercising and asserting ownership and authority” (Mahuika, 2019)

The ethics of whakapapa has its own broad array of commentary. Māori have reminded museums and curators, for example, that the true custodianship of Māori artefacts belong first and foremost to those peoples who have specific genealogical relationships with those taonga (treasures). Whakapapa, then, is part of the requirement for one to exercise guardianship or ‘kaitiakitanga’ (Mahuika, 2010). “There is a genealogy for every word, thought, object, mineral, place, and person” (Roberts 2015). The importance of whakapapa in the Māori world is paramount because it is considered crucial to assertions of Māori identity and tribal membership. Ngai Tahu leader, Tā Tipene O’Regan, stated that “whakapapa ‘carries the ultimate expression’ of who he is, and that without it he would be simply an ‘ethnic statistic’” (O’Regan 1987, p. 142). Ngāti Porou leader remarked that “whakapapa is the ‘heart and core of all Māori institutions from creation to what is now iwi’” (Mahuika, 1998, p. 219).

Whakapapa teaches us of our environment and the relationships each thing has with each other such as fresh water with stones, or kauri with whales. It is all in our whakapapa knowledge. Unfortunately, due to colonisation and Eurocentric influences, much of the knowledge is hard to find, lost or kept secret.

Sir Tipene O’Regan stressed the living and connected nature of whakapapa between ancestors and Māori in the present, stating that “my past is not a dead thing to be examined on the post-mortem bench of science without my consent and without an effective recognition that I and my whakapapa are alive and kicking” (O’Regan, 1987, p. 142).

Māori genetic data contains all of the original hosts whakapapa and various other sensitive information to the host including, diseases, health vulnerabilities, inherited memories etc.

Cosmology & Deities

For many years, and even still today, Māori cosmology is incorrectly referred to as myth, legends, and fairy tales by non-Māori, even by some Māori scholars. Reed & Calman 2008 describes these descriptive words as unfortunate terms and that some people prefer the word ‘truth’. The intergenerational misuse and contradiction of these words to describe Māori Cosmology is likely due to New Zealand (prior to the 1990’s when immigration criteria were made more open) being dominated by Christian and Eurocentric values and society not having an appetite to use non-Christian terms. It is also an intergenerational sign of the fear of the Tohunga Suppression Act 1907.

“Within the new-comers work, ancestors who were previously accepted as real and living in Māori genealogy were reimagined in fables and legends that colonisers called Polynesian mythologies and fairy tales” (Reed, 1974, p. 1). In a culture that lives and grows, there need be nothing outmoded or discredited about mythology. “Properly understood, Māori mythology and traditions provide myth-messages to which the Māori messages be more clearly sign posted” (Walker, 1978).

“Myth and legend are an integral part of the corpus of fundamental knowledge held by philosophers and seers of the Māori and indeed of the Polynesian people of the Pacific from ancient times. Myth and legend in the Māori cultural context are neither fables embodying primitive faith in the supernatural, nor marvellous fireside stories of ancient times. They were deliberate constructs employed by the ancient seers and sages to encapsulate and condense into easily assimilable forms their view of the World, of ultimate reality and the relationship between the Creator, the universe and man” (Marsden & Royal, 2003, p. 177).

Cosmology contains many warnings about Māori genetic data and the sacredness of body fluids. The first of the cosmology stories that provide warnings about misuse of DNA is about Tāne Māhuta creating the first woman Hineahuone. Tāne, with the help of his brother Tangaroa who ripped off part of his chest. But in the process of making the woman, Tane had inadvertently created many of the species of the forests, monsters, and other evil beings. The lesson in this story is that there are unintentional consequences with gene manipulation if the whakapapa is not known and if you research and manipulate genes without caution.

Māui and his knowledge of Taonga Species genetic data

Māui in Māori traditions is a famous Polynesian ancestral hero. In a western construct, we are taught that Māui is a trickster and a troublemaker. The pepeha Māui tinihanga appears to confirm this (Te Pipiwharauroa, 1909). The pepeha has been translated as Māui the trickster. Māui was noted for his tricks he played that finally this led to his death by Hine-nui-i-te-pō (Mead & Grove, 2001, p. 289). I argue that the pepeha has been myopically translated with a Eurocentric perspective.

Māui represented someone who challenged status quo knowledge and traditions, and therefore provided a “destabilising force that guarded against hegemony and opened up pathways for change” (Claw et al., 2018). Māui was a disruptive leader who provided Māori with a plethora of advancements.

There are many Māui traditions that relate that ancient Māori had intimate knowledge of Māori genetic data of all Taonga Species and that there were a number of tikanga practices. Traditional practices of transformation are what are now called genetic modification.

The first is the story of Māui transforming himself into a bird. Māui wanted to find where his mother would visit each day without inviting his brothers. To do this, Māui transformed himself into all manners of birds, of every bird in the world, and yet no single form that he then assumed had pleased his brothers. Eventually he transformed himself into a pigeon (Grey, 1995, p. 16). The story is also found in the following pepeha “Mehemea a Rupe”: “If I were Rupe”. Rupe is the personification of the pigeon. Māui changed himself into a pigeon and thus was able to fly where he wished. The expression is best applied to someone taken prisoner and wishes to escape (Brougham, 1975). Brougham 1975:34; (Grey & Solomon, 1857, p. 68).

In another story Māui turned his brother-in-law Irawaru into a dog after a disputed fishing trip, where Māui was tricked by Irawaru to use a fish hook with no barb so that he could not catch fish (Grey, 1995, p. 32). Ngāti Porou states Irawaru was turned into a dog by Māui as Māui wanted to acquire his dog tail cape (Orbell, 1995, p. 76). Such a cloak made of dog skin was valued by warriors as a defence against spear thrusts.

Māui tricked Irawaru into eating faeces. Hence dogs today often eat faeces. Irawaru is now considered the founding ancestor of dogs. The event is reflected in the following pepeha He tāpahu o Irawaru. A dog skin cloak of Irawaru (Brougham, 1975, p. 45); (Kohere, 1951, p. 136).

Rohe was a wife of Māui. She was beautiful as he was ugly, and on his wishes to change faces with her, she refused his request. Māui, however, by means of an incantation over Rohe while she was sleeping, swapped their faces. In the morning when Rohe awoke she was distraught. She then committed suicide to live in the spirit world (Tregear, 1891, pp. 233-234 & 421).

After Māui tricked Mahuika (atua of fire) into providing all of her fire, Mahuika set fire to the world and the oceans to chase Māui. Māui then transformed himself into a hawk to escape. When that proved of no use, he then asked his atua for assistance (Cooper, 2012, p. 234; Edward. Tregear, 1891).

“At a certain time, the thought came to Māui that he would strive to gain eternal life for man, that man might revive from decay as the moon does. He called together his people—the forest elves, the birds, and the multitude of the Mahoihoi—and explained to them his design. They said, “Māui, you will perish. Beware! Your spirit has been taken by Hine-nui-te-Po.” But Māui persisted, and so he and his people fared on until they found the dread Goddess of Hades, who was asleep. Said Māui to his folk, “You must be very careful not to laugh while I enter the body of Hine, lest she awaken and slay me. When I have gained [or obtained] her manawa, then all will be well. Do as I say and Hine [or her power to inflict death upon mankind] shall be destroyed.” Then Māui essayed to enter the body of Hine by the passage whence man is born into the world. But when he had half entered, the strange sight was too much for Pīwakawaka (the fantail, a bird), who laughed aloud. Hence awoke the dread Goddess of Death, who, by closing her puapua (labia) caused the death of Māui. So perished Māui, the hero, he who performed marvellous deeds, but who succumbed in his effort to gain eternal life for man” (Best, 1976b, pp. 380-381). This is the reason menstrual blood is tapu. Menstruation was seen as a medium of whakapapa (genealogy) that connected Māori women to our pantheon of atua (Murphy, 2011).

Another story states Māui assumed the form of the rat, but to this Tatahore objected, then that of a reptile, which Tiwaiwaka condemned, then that of a form of a worm, which was approved of by his companions (Best, 1924a, p. 378).

The story of Māui’s death is remembered in the following Te Aupōuri pepeha: Ko Hina kai tangata. Hina holds the power over night and day and is the cause of death. When she spread her legs wide open, it was light. Then a servant Māui-mua laughed at her and she closed her legs, causing darkness, resulting in light and darkness of the world. Māui-Pōtiki urged that death be of short duration like the night. Hina refused; she wanted death to be long so that those left behind would mourn. This is the reason why we weep the dead (White & Didsbury, 1887, p. II.80).

Classes of Atua

The primary meaning of ‘divine being’ is at the core of the term Atua, and other associations flow from this. An atua is invisible but may have visible symbolic or tangible manifestations. “Thus, in the eighteenth century the term covered gods, ghosts, unexplainable phenomena and representations of divine beings” (Benton et al., 2013).

This framework proposes seven classifications of Atua. All of which are relevant to Māori genetic data. Elsdon Best classed Atua into four categories (Best, 1922, p. 140). Sir Peter Buck added a fifth category for tribal gods (Buck, 1949, p. 460).

This research has further defined “Class 1” and added two further categories recognising the parents of the Departmental or Tutelary Deities Ranginui and Papatūānuku (point 2 below) and their grandchildren (point 4 below).

| Class | Description |

| 1 | Kore (The beginning or the darkness). Io the Supreme Being – Io is disputed with many Iwi. Most, if not all Iwi agree that there was a Kore and that there were between 10 and 12 spirit worlds with various Atua, some of whom Taonga Species are derived from. |

| 2 | The parents of the Departmental or Tutelary Deity Ranginui, Tangaroa and Papatūānuku. |

| 3 | Departmental or Tutelary Deity – The multitude of children of Ranginui and Papatūānuku. Some Iwi have the number between 72 and 74 children. |

| 4 | Second and subsequent Departmental or Tutelary Deities. These are the grandchildren and other generations of Departmental or Tutelary Deity of Ranginui and Papatūānuku. |

| 5 | Tribal Atua – An example here is an atua of Kūmara for an iwi. These are relevant to Taonga species. |

| 6 | Family atua, familiar spirits: These spirits could appear as birds, dogs, lizards or sometimes insects. These atua are relevant to human genome research. |

| 7 | Cultural heroes with superpowers such as Tāwhaki and Māui. |

Atua

The table above differs greatly from Ngāi Tahu Scholar Te Maire Tau who argues there are issues defining what myth is and what is tradition. His proposed “Oral Traditional Chart” created mainly for historians defining historical whakapapa, consists of four realms: Realm of Myth (Class 1-7 above); Mytho-history Realm (Class 1-7 above); Historical Realm (Oral) and Historical Realm (Written) which considers physical ancestors who are human beings (Tau, 2003, p. 19).

Taonga Species – Primary Atua

All of the various species and orders partook of mauri and for that reason were tapu to a greater or lesser degree. Each class type, species and genus are under the protection of its tutelary deity (Marsden & Royal, 2003). All species have a whakapapa to a number of children of Ranginui, Papatūānuku, Tangaroa and their children and grandchildren. Some Taonga Species also have a direct descent from the Māori spirit worlds. A comprehensive list in in Appendix B.

Every human being who has whakapapa Māori, has either a direct or indirect descent to Ranginui, Papatūānuku or Tangaroa, noting there are iwi variations to this. As an example, Te Arawa whakapapa states they are descendants from the stars in the heavens “Ohomairangi was born from the union of the ancestor Pūhaorangi, who descended from the heavens and slept with Te Kuraimonoa. Six generations later when war ravaged the Polynesian island of Rangiātea, Ohomairangi’s descendant Tamatekapua led his people to the North Island of New Zealand in the canoe named Te Arawa” (Tapsell, 2017).

All non-human species are the tuākana of human beings. Some Iwi can claim closer genealogical links to various species as their direct tipuna or atua.

The tutelary deities would place guardian spirits over places or things to watch over the property dedicated to them. “These kaitiaki manifested themselves by appearing in the form of animals, birds, or other natural objects as a warning against transgression, or to effect punishment for a breach of tapu” (Marsden & Royal, 2003, p. 6).

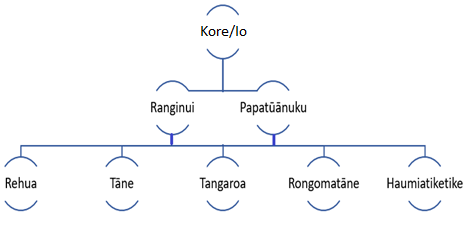

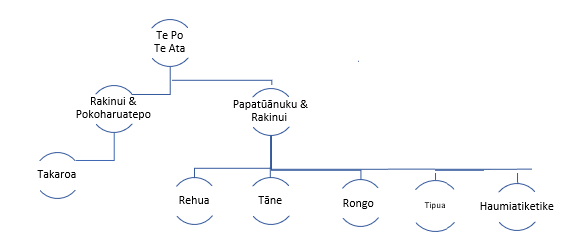

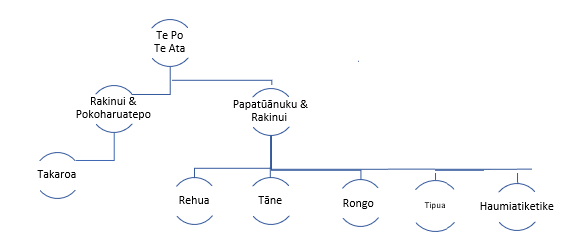

The figure below (is intended as a general summary and may differ regionally and within Iwi who may have their own variations, including not recognising Io, shows the genealogy from the genesis atua, to Ranginui and Papatūānuku, to their children who are the primary parents of all Taonga Species. From these children are offspring, the grandchildren of Ranginui and Papatūānuku who are the atua of all Taonga Species.

Whakapapa of Atua

Papatūānuku

Papatūānuku was conceived by tangata whenua as the primordial mother who with Ranginui birthed the tutelary deities and humankind. These tutelary deities’ role is to take charge over the elements – winds, forests, ocean, cultivated crops etc.

Papatūānuku is our mother who deserves to be nurtured and respected as a human mother. From unicellular through to more complex multicellular organisms each species depends on each other species as well as its own, to provide basic biological needs for existence. The different species contribute to the welfare of other species and together they help us to sustain the biological functions of their mother, as a living organicism. They also facilitate the process of ingestion, digestion, and waste disposal; they cover her and clothe her to protect her against the ravishes of her son Tāwhirimatea. She nourishes them, they nourish her.

Rehua

In Kāi Tahu stories, Rehua is the first son of Rakinui and Papatūānuku and is regarded as a very sacred atua who resides in the highest realm (12th) of the spirit worlds. Rehua gave his younger brother Tāne the seeds of all vegetation and also all of the bird species to being back to earth to decorate their mother Papatūānuku and so that the birds and insects could eat.

In many North Island stories, several atua including Māui, Tāwhaki and Tāne were given specific Trees and birds to being back to earth. These species include the senior lines of the forest such as Mānuka, Tōtara and many species of birds including Huia, Toroa, Bittern Cuckoo (Long tailed), Fernbird (Bowdleria punctate), Harrier (Cirus approximans) Heron/White Heron (Egretta alba), Mountain Parrot (Nestor notabilis), Kea and Quail (Coturnix novaezelandiae).

Tāne

Tāne Māhuta for many iwi is the tutelary deity of the forest and all its species. Tāne then created the first woman Hineahuone and bore many children to her, their first child is Tiki.

A hapū of Ngāi Tahu in Moeraki believe that Tāne Māhuta and his sister Paia produce the first human being (Orbell, 1995, p. 30). While other hapū in Ngāi Tahu state Tāne Māhuta crated Tiki Auaha as the first human being made from earth and then created a companion for himself and that they copulated in Hawaiki before coming to New Zealand (Tiramōrehu et al., 1987, p. 31).

Tangaroa

Tangaroa is the tutelary deity of all oceans, freshwater species, and reptiles. Ko te mana o uta, o te moana, ko Tangaroa. “Tangaora the influential being of land and sea” (Best, 1972, p. 772).

In Ngāi Tahu traditional knowledge, Takaroa copulated with Papatūānuku first creating a number of children. Then when he was away, Ranginui copulated with Papatūānuku creating other children.

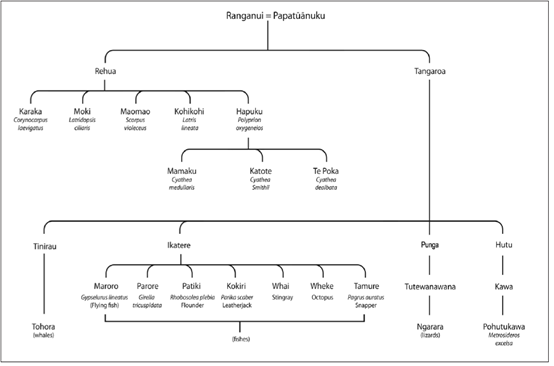

Tangaroa Whakapapa – (Roberts, M., 2013)

Rongo-mā-Tāne

Rongo is the tutelary deity of cultivated food products such as the Kūmara (Ipomoea batatas), Taro (Colocasia esculenta), Hue (Lagenaria siceraria), Ari (bloodless, dry, sapless food and herbs, hence it was used as an offering to the gods in those ancient times), Korau (root crops) as well as other crops and vegetation and such other products as may have been cultivated in past times and other lands (Best, 1910, p. 176). As the protector of crops, Rongo was appealed to as the one to cause all crops to flourish and bear abundantly.

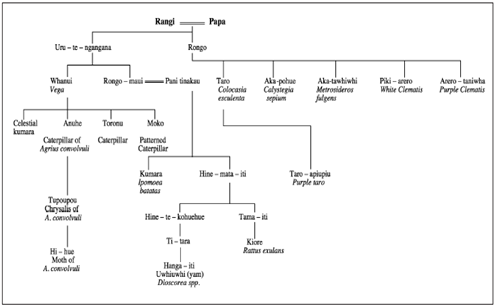

Rongo Whakapapa (Roberts, 2013)

Rongo Whakapapa (Roberts, 2013)

Haumia

The tutelary deity of all uncultivated food particularly associated with the rhizome of the Bracken (Pteridium esculentum). Some Iwi including Kāi Tahu and the Takitimu waka have Haumia as great grandson of Ranginui and Papatūānuku.

As with any whānau Māori in the physical world of humans, there are other siblings of Ranginui and Papatūānuku who act as carers (tuākana) to Taonga Species. These include Rūamoko the tutelary deity of minerals and Tāwhirimatea the tutelary deity of the weather.

Haumia is mentioned in a number of pēpeha, reinforcing his position as an atua.

Ko Rongo, ko Haumia he mea huna. Both Rongo and Haumia are hidden. This refers to the quarrel of Rongo and Haumia when they both hid inside Papatūānuku where they remain today.

Ko Haumia nāna te aruhe. Haumia of the fernroot. A reference to the Atua of fernroot Haumia.

Ko Haumia tiketike, Tangaroa hakahaka. “Lofty Haumia, low Tangaroa. Haumia the atua of bracken grows high on the hills. On the other hand, Tangaroa resides out of sight, below the sea’s surface, yet both are important to human existence” (Best & Andersen, 1977, p. 73); (Grey & Solomon, 1857, p. 52).

The following two images are based on Kāi Tahu iwi from North Canterbury whakapapa of the primary deities of Taoka Species.

Kāi Tahu Whakapapa Taoka Species

In Kāi Tahu the creation stories are very different to most other Iwi, but closely resemble the genealogy from Ngāti Porou on the East Coast of the North Island.

Ngāi Tahu Scholars including Te Maire Tau and Eruera Prendergast-Tarena argue that Io was not introduced in traditional Kāi Tahu knowledge till post colonisation. Unlike other stories, Ranginui and Papatūānuku has several relationships with other atua before their relationship. Rakinui and Pokoharuatepoo conceived Takaroa the atua of the ocean and all related species.

Papatūānuku and Rakinui had numerous children including Tāne, Rehua (of birds and seeds. Tane brought them from the 12th spirit world to Earth to clothe his mother Papatūānuku.)

Rongo is the Atua of Kūmara, though Kāi Tahu tradition states that Pou brought Kūmara from Hawaiki on the back of a giant bird named Te Manu Nui-a-Tāne. Te Kāhui Matangi people of the kaitiaki of Kūmara seeds while Tipua is the atua of uncultivated foods.

Ira Tangata/Human Atua

Ngāi Tahu Human Creation

Ngāi Tahu Human Creation

In Kāi Tahu traditional knowledge, Tāne created Hinetītama the first human, and then produced their son Tiki. While in other tribal traditions Tāne created the first human Hineahuone.

Tāne formed a body from sand then clay. He shaped and moulded it with his hands until there appeared a head. He pulled out of the earth, forming four legs and a tail. Tangaroa gave his ocean water to the clay body and when it mixed with the clay it turned red and become blood.

Tūmatauenga tore off a piece of his chest giving it to the new creation saying it will have a ‘heart of courage like mine’. Then Tane gave the clay body the “Breath of Life”. (Robinson, 2005, pp. 37-38). “Ruataiepa had a vagina pedenda muliebria; Whatai a labia; Punaweko some hair; Māhuta and Tarewa both had a penis” (Tiramōrehu et al., 1987, p. 31).

Each part of the human body has an atua associated with it and a story of creation. For example, menstrual blood is tapu, as it is the blood of Māui Tikitiki who was crushed to death when he entered Hineahuone thus making human beings’ mortal and able to reproduce (Murphy, 2011). The left side of the body is noa (free from spiritual restrictions), the right hand is tapu (Best, 1972, pp. 1088,1099). A list of atua associated with the Ira Tangata is in Appendix C.

In addition to body parts, body fluids also have a whakapapa. Traditional knowledge states the origins of all fluids from human beings (blood the only exception) originated from the seminal fluid of Tāne Māhuta after he created Hineahuone. Tāne Māhuta interfered with the whare o te ora (female reproductive organs) of Hine Ahu-one by trying to insert his penis into various orifices and ejaculating within them.

Tāne inserted his penis into the eye; the result was tears (Best, 1972, p. 767); Tāne inserted his penis into the ear: the result was earwax (Best, 1972, p. 767). Tāne inserted his penis into the nostril: the result was snot and other discharges ( Best, 1972, p. 767); Tāne inserted his penis into the mouth: the result is saliva ( Best, 1972, p. 767);Tāne inserted his penis into the armpits: the result was sweat (Best, 1972, p. 767), Tāne thrust his penis against the forehead of Hine Ahu-one; the result is sweat (Orbell, 1995, p. 54).

In the ancient Ngāi Tahu karakia recording the creation of the first human by Tāne Māhuta, is a similar story that collaborates the above sources:

Where shall I apply my penis? What about your head?

That pool is the place of the hair, not that.

Where shall I apply my penis? What about your forehead?

That pool is the place of the sweat, not that.

Where shall I apply my penis? What about your nose?

That pool is the place of mucus, not that.

Where shall I apply my penis? What about your eye?

The pool is the place of tears, not that.

Where shall I apply my penis? What about your ears?

That pool is the place of wax, not that.

Where shall I apply my penis? What about your mouth?

That pool is the place for swallowing food, not that place.

Where shall I apply my penis? What about your neck?

The pool is the place for the Adams apple, not that place.

Where shall I apply my penis? What about your armpit?

That pool is the place for the smell of sweat, not that place.

Where shall I apply my penis? What about your breast?

That pool is the place for breasts, not that place.

Where shall I apply my penis? What about your bosom?

That pool is the place for the breast, not that place.

Where shall I apply my penis? What about your navel?

The pool is the place for the navel, not that place.

Where shall I apply my penis? What about your hip?

That pool is the place for the hip, not that place.

Where shall I apply my penis? Your buttock?

That pool is the place for buttocks, not that place.

Where shall I apply my penis? Your anus?

That pool is the place for faces, not that place.

Where shall I apply my penis? What about your body?

That pool is the place for the body, not that place.

Where shall I apply my penis? What about your thigh?

That pool is the place for the thigh, not that place.

Where shall I apply my penis? What about your knees?

That pool is the place for the knees, not that place.

Where shall I apply my penis? What about your feet?

That pool is the place for the feet, not that place.

Where shall I apply my penis? What about your vagina, your vagina is the good place?

That place for the penis, the straight erection, for the bent erection.

It couples, it sports, it is full, it springs (Tiramōrehu et al., 1987, pp. 31,32).

Karakia

When the tapu fluid is moved from its donor (turangawaewae) and enters into a new environment (our physical world) there should be an opportunity to recite, or for the human donor to recite appropriate ceremonies such as a poroporoaki (farewell ceremony); mihi whakatau or pōwhiri (welcoming ceremonies) and or a karakia[15]. This recognises the donors’ biological fluids are tapu and contain wairua and mauri is entering into a new world.

A karakia is also required to be recited at the start of any work with, during, or prior to the disposal process of a Taonga Species sample, acknowledging the relevant tipuna and atua of the Taonga Species.

When obtaining a sample from a human donor, there are multiple scenarios for cultural engagement when a Taonga sample is collected, depending on the beliefs of the Māori participant.

Scenario 1

The donor should be given the opportunity to engage the DHB Māori Chaplain/Institute tikanga advisor/Whānau, who is able to provide an appropriate Christian/Anglican religious service prior to the blood sample being taken.

If the potential donor is a member of another faith, the DHB chaplain is likely to have the contacts and volumes of sacred texts of the myriad of other Māori and non-Māori religious practitioners including Pai Mārire Hauhau, Ringatū, Rātana etc

Scenario 2

The donor asks for words of a karakia so that they can recite a karakia, then a list of Christian and traditional Māori karakia should be provided.

Scenario 3

The potential donor identifies with traditional pre-colonial theological beliefs (often referred to as Ngā Atua) should be given the opportunity to either recite their own karakia before/during or after the blood is taken; or, engage and consult with a kaumātua/whānau/hapū or other culturally competent person before providing a sample. This would require a new identifier sticker to differentiate which taonga sample it is.

Fresh running water for the specific purpose of making noa the physical location and the researcher should be available where possible. If this is not possible, a container with fresh water should be available for the exclusive purpose of removing tapu. To be effective, the water must be flowing, so an area where the water can be flicked onto and around the person and the physical environment. Any left-over water should be directly placed back in Papatūānuku (earth).

Knowledge of the deities of individual Taonga Species is essential to protect the mauri of the Taonga Sample and to show respect with appropriate karakia and safety of storage.

Some examples include: Tohorā and Kauri are brothers who share common DNA; Kūmara and Fern Root who represent peace and war, hence they are enemies and should not be stored together; the common moth and the Trevally (Pseudocaranx georgianus) are related, the moth has its moko from the Trevally fish so already shares the same DNA and can be stored together.

Karakia to start work

E Rangi

E Papa

E te Whānau atua

Whakatōhia to koutou

Manaakitanga

Ki roto i tēnei mahi

O Mātou

Human Being Karakia

E Papatūānuku,

e Tāne Māhuta,

e Hine Ahuone,

e te whānau atua o te ira tangata,

whakapainga tēnei toto,

Āe!

Papatūānuku, Tāne Māhuta, Hine Ahuone and the other creators of the human body, infuse your support and care with this taonga body tissue/fluid taonga sample.

Non-Human Karakia

It is important to know the whakapapa of the Taonga Species and incorporate their names into an appropriate karakia for the iwi region you are in. Noting some Atua and Kaitiaki names vary from mare/hapū/Iwi.

An example of atua for caterpillars are below:

Tāne Māhuta – Hinetuamainga

Te Putoto – Takaaho

Tuteahuru – Hine Peke

Pukupuku (Origins of Caterpillar)

Then the relevant caterpillar name and associated whakapapa.

Maramataka

The most important functions of the Māori lunar calendar (Maramataka) are to regulate planting, harvesting, fishing, hunting, and planning for the community. “The Maramataka is the basis of the cultural life of the community, acting as an indicator of appropriate times for the onset or cessation of various activities. Much like whakapapa, the maramataka is deeply interwoven with atua, stars, weather, land, ocean and living species” (Matamua, 2017).

The names and meanings of the moon nights have ecological knowledge encoded in them, which described the influence of the moon cycle on fishing and planting activities (Ropiha, 2010). One night of the moon is referred to as a division of time and includes the whole 24-hour period (Tāwhai, 2013, p. 13). Various phases of the moon will impact on various Taonga Species and their spiritual and emotional wellbeing.

Each Iwi have their own subtle different names and times of the maramataka, so it will be dependent on the iwi affiliations of the person providing a gene sample or where the geographical location of the Taonga Species was sourced. There are more than 43 published and unpublished maramataka from a number of iwi and a preliminary analysis of the meaning of the moon nights (Roberts et al., 2006).

Consideration of relevant atua of both human and Taonga Species is required. If the person providing the genetic sample has a whakapapa to stars in the sky of the period, then the tipuna should be acknowledged. Taonga species atua in relation to the maramataka is also important.

Within the maramataka are three different periods when the human body experiences different levels of energy of High Energy, Medium Energy and Low Energy. The higher the energy the healthier the physical, mental, and spiritual sides of the human body are. During these high energy days, are when human beings should have any gene extraction, editing and sequencing should occur.

Culturally safe laboratory

All samples from a Taonga Species should be referred to as a Taonga Sample. This signifies that the sample is precious to Māori, whānau, hapū, marae, rōpū Māori and Iwi and that it needs to have Te Tiriti o Waitangi protections and considerations and be treated with appropriate cultural practices.

There are cultural, ethical, and spiritual implications of working with Māori biological data from any Taonga Species. As DNA from a Taonga Species is tapu and contains whakapapa from the physical, cognitive, and spiritual realms, the place of extraction, analysis and research must therefore be made clear of all spiritual obstructions (noa).

To make the laboratory, storage, place of extraction, testing or sequencing noa is the same practices as if you have a physical taonga, or a tūpāpaku (dead body). The physical area should be made off limits to all food and beverages, this includes in the pockets of people and in any containers such as bags and lunch boxes. Cell phones and computers should be away from the area and if possible, all Wi-Fi and Bluetooth should be switched off.

The people working with the Māori genetic data from a Taonga Species should not be ill or have any terminal illness. For women, some caution should be considered it they are pregnant. The researchers should all be fully versed in their own whakapapa.

Māori biological materials need to be stored and handled as they are a complete tūpāpaku or koiwi (corpse). Māori biologic data should be stored in a wāhi tapu (sacred place with secure and limited access). A separate bio bank for Taonga samples is most appropriate and a system that catalogues the donor’s iwi and hapū.

Indigenising/Māorification of gene bank and database of Taonga Samples is to consider it as a waka huia. Waka huia were used to store valuables and treasures (Phillipps, G., 1963). A gene bank and its software and database(s) and the physical server and computers also should be treated as tapu and considered as a waka huia.

Access to the Māori genetic data held in the wāhi tapu database and biobank should be restricted and provided only in consultation with a Māori Advisory Committee, kaumātua or other Māori authority acting upon the advice of the whānau, hapū or Iwi.

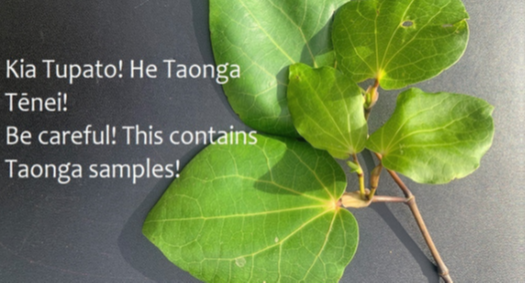

The Māori biological data should be handled, stored, and transported with appropriate traditional Māori customs including separate and clearly labelled packing that highlights the contents as sensitive items (Otago Museum Trust Board, 2014, p. 11).

Identification of Taonga Species Samples

Tonga Samples must be easily identified from non-Taonga Samples, allowing the appropriate respect and cultural practices to be enacted. The usage of a Kawakawa label is explained further here.

As biological data has a mauri, hau, wairua and whakapapa and is a Taonga, consideration must be taken when storing data and genetic material of the living and the dead. The Taonga Species biological data of the living and the dead should be separated where possible.

Consideration of the genealogical narratives of the species Māori biological data is also important. Storing Māori genetic data of Kūmara with Fern samples is not appropriate (Henare, Holbraad, & Wastell, 2007).

Care and consideration for an appropriate label is required and it is not acceptable to merely find an image off the Internet to use. An appropriate sticker should be a colour sticker that is easily identifiable to the lab clinician/researcher. The colour could be blue representing the epistemology of blood from the Māori creator of blood Tangaroa, or red/brown which also represents the origins of blood as the Papatūānuku who provided Tāne with red ochre to mix with his body fluids to create blood for human beings.

If there is a desire to use an image, then an appropriate image is of a Kawakawa leaf (Macropiper excelsum) which is used to protect the living from the dead and the dead from bad luck etc.

Kawakawa, is a sacred tree and in many Iwi is said to be a tuākana brought directly to earth from the higher spirit worlds, hence it is one of the more tapu trees. Kawakawa can signify respect to the dead. Green is also the colour of mourning and the colour of welcome. The intention of the Kawakawa leaves as a label is twofold. Extracting the Taonga Sample interferes with the hau, mauri and wairua of the person or Taonga Species that the sample was taken from.

The sample will be in a foreign environment, isolated from the kaitiaki (donor) who once protected the sacred sample that contains whakapapa. It is most likely that the end result of the sample is that it will be destroyed.

The intention of taking the sample is to provide new knowledge or to verify a western science is mātauranga Māori. Therefore, a Kawakawa image both shows a new beginning and that the sample will be destroyed. The sacredness of the Kawakawa also protects the hau, mauri, whakapapa and wairua while is isolated.

Examples of Identification Labels

The following are examples of an appropriate label to distinguish between Taonga and non-Taonga samples. These labels can be used for Freezer Tops, Tubes and Rack/Box labels

The Kawakawa in the image was taken from Ōhikaparuparu/Sumner in Canterbury using appropriate karakia and ceremonies.

Tonga Species Freezer Top, Rack and Box label

Tonga Species Freezer Top, Rack and Box label

Tonga Species Tube labels

Tonga Species Tube labels

Disposal

Article II Te Tiriti o Waitangi/The Treaty of Waitangi gives Māori the right to “tino rangatiratanga over their own taonga. In relation to the disposal of a taonga biological materials this is the right to practice traditional cultural practices that were practices when disposing of a body or a body part including body fluids such as blood and other materials from accidents and warfare.

Any left-over biological matter whether fluid, in a tissue, swab, gel, syringe, glove or other consumable, should be offered to the donor, or disposed of in a culturally appropriate manner that may involve a religious person or a kaumatua/whānau/hapū or other culturally competent person.

New Zealand health facilities have guidelines in place for disposal of human remains and organs. Māori genetic data on foreign materials is no different. If equipment needs to be sterilised, then where possible, the water that was set aside for karakia and to make noa, could be used to initially rinse the equipment over Papatūānuku.

Separate disposal streams and receptacles should be maintained for any tube, disposable equipment (e.g., needles, butterfly sets) or plate that has been in contact with a Taonga Sample. These should be stored separately in a dedicated freezer and disposed with a cultural ceremony.

Any reagents or washings that have been used for the Taonga Sample should also be frozen and stored for appropriate disposal or placed into the ground.

Any organisation with Māori biological data should have appropriate plans to cooperate with whānau, hapū, iwi or kaitiaki for the repatriation of Māori genetic data in its care, under the guidance of a Māori Advisory Committee, kaumātua or other Māori authority acting upon the advice of the whānau, hapū, Iwi or kaitiaki.

Returning of a deceased Taonga Species sample

It is cultural best practice in the case of a deceased study participant, for whānau (for a human) or representative group such as hapū, iwi and kaitiaki to request the return of any stored sample(s), and to request the data is withdrawn from the study database, or for the sample to be destroyed in a culturally appropriate manner if Health and Safety are a concern.

The return of any biological materials from a Taonga Species to the marae/hapū/Iwi or Kaitiaki should be planned with them and could require a formal Pōwhiri and other cultural ceremonies.

Hirini Mead (2003) has developed a framework using Tikanga Māori and Mātauranga Māori to assess contentious issues to find a Māori position on these issues. This test and the proposed models below should form the basis for any decision-making process involving aa request by whānau to return the deceased Taonga Sample.

The following Tikanga Test should be offered to the whānau (or other group) requesting the return of the sample.

Test 1: The Tapu Aspect – Tapu relates to the sacredness of the person. When evaluating ethical issues, it is important to consider whether there will be a breach of tapu, if there is, will the gain or outcome from the breach be worth it.

Yes, there will be a breach of the individuals tapu. The breach can be mitigated with the fact that the sample will be stored in a culturally safe environment. The intended research of the sample will be of benefit to the whānau, hapū and Iwi of the individual or wider te ao Māori.

A question may be that the sample was provided for the betterment of their whānau/te ao Māori. Would this still be achieved?

Test 2: The Mauri Aspect – Mauri refers to the life essence of a person or object. In an ethical context, one must consider whether the Mauri of an object or a thing will be compromised and to what extent.

Yes, the mauri will be compromised to a certain extent. The long-term goal is to provide more protection of the mauri for the donor, their whānau, hapū, Iwi and environment.

Test 3: The Take-utu-ea aspect – Take (Issue) Utu (Cost) Ea (Resolution). Take-utu-ea refers to an issue that requires resolution. Once an issue or conflict has been identified, the utu refers to a mutually agreed upon cost or action that must be undertaken to restore the issue and resolve it.

Results should be shared with the individual and plans to address equity issues created. An Annual open day should be held for participants and whānau to visit the lab facilities and this would be advertised through culturally appropriate media.

Test 4: The Precedent aspect. This refers to looking back at previous examples of similar issues that have been resolved in the past. Precedent is used to determine appropriate action for now.

This will need to occur on a case by case basis as this technology and ethics are only recently being introduced and created.

Test 5: The Principles aspect. This refers to a collection of other Māori principles or values that may enhance and inform an ethical debate

Issues such as those listed in the Community-Up Model: manaakitanga, mana, now, tika and whanaungatanga (Smith & Cram, 2001) or the Māori Data Ethical Model (Taiuru, K. 2018) should be considered.

Hybrids/GMO/GE involving Taonga Species

The following statement is from Ngāti Kahungunu tribe to the Waitangi Tribunal which highlights the need to consider Māui and his knowledge of genetics “For like much of the boosterism of gene research he (Māui) saw the opportunity to unravel the mysteries of life, to prolong it, and even change it. Yet in the excitement of new opportunity, he neglected the wisdom of the past and did not take the time to properly assess the risks. He knew that there might be dangers but assumed that he could minimize or control them. And he failed, because in a very basic sense he had not asked of death why do we need to know?” (Ngāti Kahungunu Iwi Authority and Te Rūnanga Roia o Kahungunu, 2001).

In traditional Māori social society, there were rules of procreation. The pepeha “Honoa te pito ata ki te pito maoa” translates as “Join the raw end to the cooked end”. According to Grey “a rangatira (chief) often married a woman of lesser rank”. The saying, apparently, was the proverbial basis for such a union. Colenso suggests it also applies to the “allying of a weak or improvised tribe with one better-off, perhaps through intermarriage” (Brougham, 1975): (Colenso, 1879); (Grey & Solomon, 1857). Non-Human Species are no different, hence knowing and respecting the genealogy and local traditions allows for appropriate genetic modification and hybrid practices to be completed.

Centuries of genealogical and traditional knowledge regarding Taonga Species have been succeeded from generation to generation. Māori share a belief with many other Indigenous Peoples that species and germplasm are all intimately interrelated with each other and to human beings because of their genetic whakapapa.

There is an incorrect colonial argument perpetuated by New Zealand scientists and the New Zealand government that breeding or genetically modifying a non-Taonga Species/Exotic Species with a Taonga Species will not create another Taonga Species. Successive governments all over the world have applied the same argument to Indigenous Peoples who are descendants of mixed heritages.

While New Zealand legislation does not promote blood quantum with human beings, legislation perpetuates blood quantum doctrine with non-Human Taonga Species. Whakapapa rights with non-human Taonga Species are not recognised. The Plant Varieties Act 1987 does not recognise hybrid species that originated with a Taonga Species as being a Taonga Species. The modified species is referred to as a ‘Hybrid’. The Patents Act 2013 also does not state that any biological material from a Taonga Species requires Māori Advisory Committee approval.

If modifying genes from a non-Taonga Species with a Taonga Species, then the same narrative and whakapapa considerations are still required. But it should be ascertained if the non-Taonga Species would likely be at odds with the Taonga Species in relation to whakapapa. An example is Kūmara and a prickly plant. In Māori epistemologies it is stated that the Kūmara is from the deity of peace and prickly plants represent war and other unpleasantries, therefore are from the deity of war Tūmatauenga. Therefore, you should not use genes from a Kūmara into another species to eradicate a non-Taonga Species pest.

Gene Drives are acceptable once the whakapapa of the taonga species are known. An ancient form of gene drives occurred within the Ngāi Tahu district of the South Island with a practice called whakawhiti kaimoanato. This practice used the Pōhā (Macrocystis pyrifera) to transport and propagate live seafood such as shellfish, starfish, and Pāua etc., to neighbouring cockle beds and other areas to assist reproduction of kai moana that were experiencing growth and reproduction issues. This customary practice was undertaken by those with intimate whakapapa knowledge of the Taonga Species and history of the geographical area.

Genetic modification is acceptable between some Taonga Species, but the whakapapa of each needs to be known to avoid conflicts in whakapapa.

With no legislative protection in New Zealand for non-Human Taonga Species, the protection of Taonga Species relies on Māori Data Sovereignty, the United Nations Declaration of Indigenous Rights, and the Kyoto Protocol, yet these are not widely acknowledged or recorded in legislation by the New Zealand government.

Any variation and modification of a Taonga species with another non-Taonga/Exotic species will produce another Taonga Species. In the same manner that when a Māori and non-Māori human being procreates with each other, their offspring is still Māori as legally stated in New Zealand legislation. If multiple species are used to modify one or more non-Taonga Species the end product is still a Taonga Species. It is important to record where all of the Taonga Species were sourced from for the hybrid so that correct consultation with the kaitiaki can occur.

A Taonga Species has whakapapa to New Zealand and to Māori, whānau, hapū and Iwi regardless of parents and conception. While the same species may be found in other parts of the world, those species are not a taonga as they do not have a whakapapa and mauri from being in and on Papatūānuku.

While a certain Iwi may be the overall Kaitiaki in a western sense, the local hapū or whānau are the manawhenua and in many instances the rightful kaitiaki. Therefore, any species that reside or are taken from an iwi boundary are therefore under the auspices of the kaitiakitanga of the hapū or whānau, manawhenua, land trust or Iwi. Regardless of if Māori still own the land or not, it still contains wāhi tapu (sacred places) and mauri of the whānau, hapū and or iwi and these rights must be acknowledged and respected when using Taonga Species.

Because genetic Māori data has a mauri, whakapapa (geographic origins) the exact geographical location of the species that is to be genetically modified must be identified and recorded, not because of any system requirement or law, but because it is tikanga Māori. The responsibility is on the data collector to record where the genetic data came from, what the data is about, Iwi and hapū connections, and kaupapa Māori categories for metadata and to treat the data with respect.

By identifying the exact location will enable researchers and scientists to identify the appropriate marae, whānau, hapū or Iwi that must be consulted and engaged with before any further developments are completed. If it is not possible to ascertain the appropriate kaitiaki, marae, whānau, hapū or Iwi there are two options. Use the same species, but from a different geographical location, or speak to the closest identifiable marae, whānau, hapū or Iwi for further information. This step is essential to identify who to discuss any issues identified with Mead’s Tikanga Framework.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.