Author: Karaitiana Taiuru

Published: May 04, 2020

ISBN: 978-0-9582615

ISBN: 0-9582597-6-3 (Digital) Download

Citation: (Taiuru, K. 2020. Treaty of Waitangi/Te Tiriti and Māori Ethics Guidelines for: AI, Algorithms, Data and IOT. Retrieved from http://www.taiuru.Maori.nz/TiritiEthicalGuide).

Copyright

© Copyright Treaty of Waitangi/Te Tiriti and Māori Ethics Guidelines for: AI, Algorithms, Data and IOT by Karaitiana Taiuru is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at http://www.taiuru.Maori.nz/TiritiEthicalGuide

Acknowledgements

I am deeply greatful to Goethe-Institut Sydney who fully supported me to attend their conference as a speaker and participant at “The relevance of culture in the age of AI” in Sydney in 2019. Then again to Goethe-Institut Germany for the opportunity to attend another conference as a participant at the International cultural symposium/Kultursymposium in Weimar Germany in 2019. Both opportunities allowed me to meet with and discuss AI issues with globally recognised experts in the field of AI. It was also an opportunity to gain a first-hand experience and interaction with AI leaders, Indigenous practitioners, and activists from around the globe. This experience for me, reinforced the need for some kind of regulation for at least Māori protections with not just Data Sovereignty but with AI and other emerging technologies.

The Department of Internal Affairs and the World Economic Forum (WEF) brought together a number of interested parties including a number of Māori practitioners for a one-day workshop called Re-imagining Regulation in the Age of AI’ workshop in October in 2019. A small group of the participants formed to create a Te Tiriti working group. This group was forced to prematurely cease before any major progress could be made. This was further motivation to write this paper alone and then seek the co-operation of others to peer review.

From the working group, a special thank you to Kaye Maree Dunn (Te Rarawa, Ngā Puhi, Ngāti Mahanga, Ngāi Tāmanuhiri, Ngāi Te Rangikoianaake), Amber Craig (Ngāti Kahungunu ki Wairarapa, Rangitāne, Muaūpoko) and Anna Pendergrast (Ngāti Pākehā) for their continued assistance and support from the workshop.

About the Author

Ko Karaitiana Taiuru tōku ingoa. He uri au o Ngāi Tahu (Koukourarata, Puketeraki, Rāpaki, Taumutu, Tūāhuriri, Waewae, Waihao, Waihopai, Wairewa), Ngāti Rārua, Ngāti Kahungunu (Ngāti Pāhauwera), Ngāti Hikairo (Ngāti Taiuru), Tūwharetoa (Tamakopiri), Ngāti Hauiti (Ngāti Haukaha), Ngāti Whitikaupeka.

I have iwi affiliations to: Ngāti Tama, Ngāti Ruanui, Te Ati Awa, Taranaki, Ngāti Hauiti, Whanganui, Tūmatakōkiri, Ngāti Kuia, Ngāti Koata, Ngāti Apa ki te Rātō, Ngāti Ruanui, Ngāti Ranginui, Ngāti Porou, Waikato/Tainui (Ngāti Tipa, Ngāti Tahinga, Ngāti Māhanga, Ngāti Apakura, Ngāti Maniapoto).

My name is Karaitiana Taiuru. I have a number of iwi (tribal) links and affiliations. My knowledge of tikanga, Māori customs, te reo Māori and other aspects of Te Ao Māori I learnt as a child growing up with my kaumātua, including several of the last tohunga of my hapū, while living beneath my sacred mountain Maukatere. I was also fortunate to also have gained knowledge from my marae Maahunui I in Tuahiwi and from visiting many Ngāi Tahu and North island marae including time spent at Ratana Pā.

I began working in what was previously called the IT industry in 1995 as an electronic book creator. My first project was Te Reo Tupu, a Māori Dictionary compiled from all of the (at the time) published Māori dictionaries into a searchable database.

I have been involved with multiple Māori ICT projects and achieved many first milestones for Māori including the world’s first un moderated Indigenous domain name, the world’s first moderated domain name moderator for the past 20 years, significant developments with Māori language revitalisation with ICT, a member of a number of advisory and governance positions in New Zealand (NFP and New Zealand Government) and internationally representing Māori and Indigenous perspectives with various ICT areas and a well-established Māori culture and ICT blog.

By 1997, I was acutely aware of the need for ethics with IT and Māori culture, but at that time, IT was frowned upon by many kaumātua and the very few Māori who were in the industry at the time.

I graduated from the University of Canterbury with a Master of Māori and Indigenous Leadership with Distinction. Motivated by western perspectives dominating the digital industry, even by Māori, I embarked on and am in the final year of a PhD researching customary Māori rights and Property Rights with genetic research and data.

As part of that research, I have been an invited guest speaker to multiple organisations and provided part of a chapter from my thesis to the Waitangi Tribunal in 2019 as an expert witness refuting Crown understandings and publications of tikanga and customary Māori knowledge with bio technology and whakapapa.

Background

Digital technologies have a key role to play in advancing solutions to complex issues affecting Māori. The opportunities will go unrealised if Māori are not included in the development of these technologies. Māori communities are especially vulnerable to privacy-related risks that come with (for example) the collection and storage of data on individual persons. The risk of individuals and whānau being re-identified through anonymised data is heightened when dealing with minority groupings and with sparsely distributed populations such as Māori. The heightened risks for Māori communities require these ethical guidelines to be created.

Internationally there are widespread reports and cases of discrimination against minority groups including: Indigenous Peoples, People of Colour, LGBIT and Women with Artificial Intelligence, Algorithms and Data. In turn, this has created international discussions about the need to regulate AI and related technologies or assume that AI systems developments will be the better off for the wider community without regulation.

Statistically, both here in New Zealand and internationally, it is middle aged white males who dominate decision making positions and whom are in positions of authority and influence, more so in the ICT industry. This same group of people are also more likely to be opposed to regulation of Artificial Intelligence. Yet, they are also the only group most likely not to be discriminated against in society or with algorithms and AI. For just this reason alone, it is a powerful reason why we need all AI and algorithms to be co-designed, co-initiated and co-governed with Māori and or Iwi.

The counter arguments to regulation to safeguard against bias, is that it is quicker and easier to teach algorithms and AI that a certain bias is not good. Unlike a human being who has inherited and learnt biases, it is very difficult or even impossible to change the thinking of a human being. This counter argument while it may be true, does not consider the impacts of the system while it is being trained to learn that a bias is not appropriate. It also still requires humans’ minorities to apply ethical considerations to data and algorithms.

Ethical government departments and New Zealand companies in today’s digital revolution need to do more than just complying with legislation. They also need to recognise the value of Data and that Data is a Taonga. They need to follow and acknowledge the Treaty of Waitangi/Te Tiriti principles.

There is a need to comply with Māori cultural protocols; the importance of digital development and use being guided by cross-cultural collaborative approaches; and the need for transparency that ensures that “Māori people, whānau, hapū, Iwi and organisations are clear about how AI learning is generated and why this information is used to inform decisions that affect Māori .”

Previous (arguably successive) governments have created legislation and initiatives that were supposed to be for the betterment of Māori; Instead, they were cultural assimilation tools that promoted colonial settler beliefs over Māori beliefs. This has resulted in the near assimilation of the Māori language, culture, whānau values and created intergenerational social, economic, and psychological impacts on Māori that are still evident today.

Examples include:

- The Native Schools Act 1867 that established a national system of village primary schools under the control of the Native Department. The primary aim was to educate Māori children so they could be integrated into society. The consequences included land was stolen from Māori and Māori children were physically beaten for speaking Māori language.

- Tohunga Suppression Act 1907. The government of the day believed it was best to outlaw traditional Māori practices of healing and spirituality, and Māori religious beliefs. The Tohunga Suppression Act 1907 made it illegal to practice traditional Māori healing and spirituality and Māori religious beliefs. A form of healing that is making a comeback due to the success of natural remedies. We see an ongoing detriment to this with the discrimination of Māori in the health system in WAI 275 and high rates of sickness and mortality among Māori.

- The Hunn Report 1960 claimed that integrating Māori into Pākehā society was the answer, rather than strengthening their separate cultural identity would assist Māori. The ramifications were huge on communities and Māori and are still evident today with social, economic and loss of culture.

- There are many other modern-day examples such as: Health, Justice, care and protection of children; all of whose data will likely be used in future algorithms and AI systems.

In New Zealand we are already seeing AI systems, proposed algorithm charters and international instruments being created by the New Zealand government and others with inappropriate or no consultation with Māori and no Treaty of Waitangi/Te Tiriti recognition.

These actions reflect a move from the physical world of inherited bias and unconscious racism to now being applied in the digital eco system. The issue with the digital eco system is that the impacts are exponentially faster, and the consequences are mammoth.

It is important to let Māori customs and mātauranga guide the design process of all digital systems, not the system to guide and shape Māori customs and mātauranga. These guidelines will assist that process.

Introduction

These guidelines are primarily intended to be used by New Zealand government agencies/departments and organisations engaging with digital projects involving New Zealand and Māori Data. There is a recommendation for an explicit Treaty of Waitangi/Te Tiriti clause for any New Zealand government initiated and or procured Artificial Intelligence System, Algorithms and system that uses Māori Data.

These guidelines consider how Māori people and communities may be impacted by emerging technologies, with much less attention given to the role of Māori people as users and potential innovators. It is important for Māori involvement in the collection and analysis of data. There is a need for participation and agency in shaping AI and other digital systems agendas, recognising the importance of including Māori communities in tech development and in the design of policies, and the matter of Māori data sovereignty.

It would be a great injustice creating one set of ethics for Māori Data or any other system that uses Māori Data, as Māori culture is so diverse. The ethics required for a facial recognition system are at different ends of the spectrum than for a machine learning system with te reo Māori. Māori Data that is comprised of Māori Genetic Data involves a unique set of complex customary and Property Rights considerations. Therefore, these guidelines are intended to be a guide to creating a set of specific ethics for AI, Data and Algorithm projects using the guidance of expert Māori advisors.

To address some of these discrepancies, the proven kaupapa Māori frameworks are provided to work through. The Tikanga test will establish which data requires cultural consideration and what aspects of culture can be compromised. The data sovereignty guidelines allow a high-level scope, while the Data Ethical framework will ensure that the results from the Tikanga Test and the data sovereignty guidelines are treated in a culturally appropriate manner.

Also, included in the guidelines are a set of definitions to assist proper and reliable Treaty of Waitangi/Te Tiriti and Te Ao Māori considerations of which will assist removing biases against Māori and will provide monitoring and protection mechanisms in a fair and ethical manner that also observes New Zealand’s commitment to Te Tiriti.

Large parts of my thesis were used for the following sections: What is Tikanga, Te Ao Māori Perspectives and Disclosure.

What is Tikanga?

Tikanga Māori has become a common term in modern society. Understanding what tikanga means vary considerably. Though a few people are quite knowledgeable, the vast majority know little about the subject (Mead, 2016). Mead defines tikanga as “Referring to the ethical and common law issues that underpin the behaviour of members of whānau, hapū and iwi as they go about their lives and especially when then engage in the cultural, social, ritual and economic ceremonies of their society ” (S. M. Mead, 2016, p. 16).

Tikanga Māori translates as Māori custom. They denote those customs and traditions that have been handed down through many generations and have been accepted as a reliable and appropriate way of achieving and fulfilling certain objectives and goals. Such proven methods together with their accompanying protocols are integrated into the general cultural institutions of society and incorporated into the cultural system of standards, values, attitudes and beliefs (Marsden, Henare, & New Zealand. Ministry for the, 1992).

Tikanga does not preclude new circumstances and needs as they arise. But before creating new tikanga for modern day circumstances, one must have an intimate knowledge of traditional knowledge first. Tikanga must not be obfuscated to suit one’s own needs and personal circumstances as research suggests occurs in academia and government consultations (Hutchings, 2005). Other reasons for obfuscation could be due to a lack of te reo Māori, being raised off the marae or having non-Māori religious beliefs.

(a) Tikanga in modern day society

A common argument against tikanga and customary rights are that they are no longer relevant in modern society (Archie, 1995). The same is often said of the Holy Bible and other religious literature. .

Tikanga and the Treaty of Waitangi are both relevant and are unique building blocks for modern day New Zealand society. For many Māori, traditional tikanga is still applicable and highly relevant, though for some it is just instinct that cannot be described.

A culture cannot be learned from a textbook. True understanding and appreciation are possible only from first-hand-experience. Māori have continued to maintain customs that they have developed and nurtured for many, many generations. It is essential for all New Zealanders that the Māori maintain integrity of their culture rather than permit adjustments that are simply intended to make it easier for the non-Māori to fit in (Tauroa & Tauroa, 1986, p. 13).

Māori academics have institutional boundaries they must work within. Western sciences and knowledge institutions often do not recognise traditional knowledge, therefore how do Māori academics within western institutions publish material about tikanga and mātauranga Māori? Cooper states that Māori knowledge has been cast by Western science into an epistemic wilderness, and Māori are regarded as producers of culture rather than knowledge.

The position of Kaupapa Māori is paradoxical. It must stand aloof from the concerns of science and centre Māori epistemologies as a starting point for research. At the same time, it must critically engage Western knowledge and production practices as part of its decolonizing and transformational strategy (Cooper, 2012).

The New Zealand Human Rights Commission recognises the need to include Māori spirituality as a fundamental tikanga. Māori spirituality is an inherent part of tikanga Māori, linking mana Atua, mana whenua and mana tangata. The recognition and protection of tikanga Māori (culture), in accordance with international human rights standards and with the Treaty of Waitangi, therefore, cannot be separated from Māori spiritual beliefs (New Zealand. Human Rights, 2004, p. 2).

(ē) Statutory Recognition of Tikanga Māori

The New Zealand Law Commission defines tikanga:

“as well as common law, Māori custom law or tikanga must also be taken into account. While there is ongoing debate and discussion as to the precise status of tikanga within New Zealand legal systems, there is no doubt that consideration of tikanga and its underlying values will be taken into account by the courts when adjudicating disputes involving Māori deceased or Māori custom. Rules and customary practices based on tikanga have also evolved over hundreds of years and give expression to the fundamental principles, values, and beliefs which underpin Māori culture (Law Commission, 2001). Since 2004, tikanga has been mentioned in more than 253 judicial decisions of New Zealand’s Supreme Court, Court of Appeal and High Court (from 2005) twice in Family Court judgments in 2019 and 2020 (Justice, 2020).

In Huakina Development Trust v Waikato Valley Authority [1987] 2 NZLR 188, Chilwell J applied Public Trustee v Loasby (1908) 27 NZLR 801 to find that “customs and practices which include a spiritual element are cognisable in a Court of law provided they are properly established, usually by evidence.” He held that “Māori spiritual and cultural values could not be excluded from consideration if the evidence established the existence of spiritual, cultural, and traditional relationships to natural water held by a particular and significant group of Māori people.

It has been argued that tikanga Māori and religion have enough in common that the legislative protection of tikanga has the potential to affect New Zealand’s status as a secular State and its protection of religious freedoms (Wright, 2007). Furthermore, Wright recommends that legislative references to tikanga Māori should come with a clear statement of purpose. In addition, many tikanga Māori provisions should prompt advice to the Attorney-General under section 7 of the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990, even though few may ultimately warrant a section 7 report being tabled in Parliament.

Te Ao Māori Perspective

Increasingly bureaucrats and academics are using the term Te Ao Māori as fluid term when it is convenient to include a Māori perspective and there are increasingly assumptions that there is a single Māori worldview.

Te Ao Māori acknowledges the interconnectedness and interrelationship of all living and non-living things via a spiritual, cognitive, and physical lenses. This holistic approach seeks to understand the while environment, not just parts of it. There is no one Māori world view, in as much as there is no one New Zealander world view. Māori are diverse as a people. The term is sometimes incorrectly interchanged with the term ‘mātauranga. Mātauranga refers to soundly based knowledge and how it is attained. However, as colonisation proceeded, its range was extended to include education and knowledge generally, along with information (Benton, Frame, Meredith, & Te Mātāhauariki, 2013).

In Te Ao Māori, all knowledge is sacred and a taonga. According to our cosmology stories, Tāne, one of the more than 70 children of Rangi and Papa, is the creator of the human race, ascended into the heavens and brought back all of the worlds data and knowledge to share with human beings.

(a) Colonisation

For over 260 when Captain Cook and his ship the Endeavour visited New Zealand, Māori culture has been integrated into European culture by colonisation, intermarriage, introduced and forced religion, urbanisation, wars, mass murders, land theft, government-imposed cultural assimilation and racist policies including segregation of Māori communities in towns such as Pukekohe (Bartholomew, 2020). As a result, many Māori ignored or abandoned (forced or by choice) their traditional knowledge systems and beliefs. Elsdon Best remarks that the old men of Tūhoe will assert that the greatest aitua of modern times was their forsaking the ancient beliefs, religion, customs, tapu, etc., of their race and the adaption of those of the white man. Hence the degeneration lack of vitality and lessoned numbers of the Māori people. (Best, 1972, p. 1014).

Consideration of who you seek Māori advise from is also essential. All Māori are born with whakapapa, but not all Māori are Māori practitioners. In 1970, Sir Timoti Karetu expressed his concerns at the lack of understanding of Kawa (protocols, customs) in marae (Karetu, 1970). Sir Hirini Mead asserted that in 1979 it was obvious that few people really understood tikanga, and this included our own people (Mead, 2016). Ngāi Tūāhuriri Upoko and Canterbury University Scholar, Professor Te Maire Tau has described the lack of cultural knowledge within the Ngāi Tahu Iwi “Ngāi Tahu have been so colonised and have lost their identity, that it would be difficult to garnish any traditional knowledge. (Tau, 2001, p. 148).

(e) Conclusion

It is incorrect to assume there is one Māori perspective. The term “Te Ao Māori Perspectives” should only be included in AI, Data, IOT and Algorithm documentation after careful consideration and consultation. If it is to be included, as a minimum, the Kaupapa Māori Framework Te Whare Tapa Whā discussed in these guidelines should be adhered to.

Disclosure

Māori Data and digital systems about Māori, require a moral obligation to disclose source, purpose and other relevant information.

In Te Ao Māori, transparency is accomplished with a customary practice of recognising whakapapa. In its simplest sense whakapapa is genealogy, in a wider sense whakapapa attempts to impose a relationship between an iwi and the natural world. Whakapapa is one of the most prized forms of knowledge and great efforts are made to preserve it (Barlow, 1991, p. 174).

Whenever possible, consent should be sought from the participants whose data is used. In practice this means it is not sufficient to simply get participants to say “Yes”. They also need to know what it is that they are agreeing to. So far as is practicable, it should be explained what is involved in advance and obtain the informed consent of participants to have their data used. However, it is not always possible to gain informed consent. Where it is impossible and after using the Kaupapa Māori Frameworks discussed in these guidelines, a similar group of people, whānau, hapū or Iwi can be asked how they would feel if it was their data being used or new data being created about them. If they think it would be OK then it can be assumed that the real participants data will also find it acceptable. This is known as presumptive consent.

In order that consent be ‘informed’, consent forms may need to be accompanied by an information sheet for participants setting out information about the proposed system (in lay terms) along with details about the staff involved and how they can be contacted. This aspect in Te Ao Māori is termed kanohi ki kanohi (face to face). Though contact will likely be in other forms than in person communication.

There is an ever-increasing amount of Māori students who have attended bilingual and full emersion Māori langue education institutes their whole lives, who are now entering the work force and becoming adults. This cohort expect tikanga and te reo Māori to be normalised. All disclosure documentation should be written in both English and Māori. Bilingual forms and information also show a respect for treaty of Waitangi/Te Tiriti and for our taonga te reo.

The following are key questions sourced from international ethical guidelines and Treaty principles, which should be disclosed to Māori at all stages of the disclosure, planning and development cycle.

(a) Key Questions

The following are a number of key questions that should be considered.

- What is the origin of the Data?

- How was the Data authenticated as Māori?

- How was the issue of multiple Iwi affiliations addressed?

- Who owns the data, algorithm and the system as a whole?

- Explain the algorithms – the criteria and parameters?

- Do you use machine learning / artificial intelligence? If so, can you explain the algorithms – the criteria and parameters?

- In which country is your data stored?

- Where is the storage solutions provider headquartered?

- Does the transmission of data go through countries outside of New Zealand?

- Do you sell data to third parties?

- Do you sell data as personal identifiable data?

- Do you sell data as patterns on an aggregated level?

- Do you use third-party cookies? Does this include SoMe (social media) cookies and SoMe logins?

- If you use third-party cookies, are your users fully aware that your cookie use leads to sharing of data about your users with third parties and do they agree with it?

- Do you require and control the data ethics of your subcontractors and partners?

- Purpose of the system?

- Access and licence types?

- What testing and preventative measures are in place to identify and prevent biases

- What testing and preventative measures are in place to monitor a Te Tiriti obligation?

- What are all of the foreseeable risks of the system and its data?

- Benefits of the system and or Data to Māori, Iwi, Hapū, Whānau and individuals?

The Treaty of Waitangi/Te Tiriti o Waitangi

The Treaty of Waitangi/Te Tiriti o Waitangi has two texts: one in te reo Māori and one in English. The Māori text does not translate into the English text. Therefore, the Māori version should be considered. This is referred to as Te Tiriti.

The Treaty of Waitangi is one of the major sources of New Zealand’s constitution[1]. The Treaty of Waitangi is the founding document of New Zealand. It is an agreement entered into by representatives of the Crown and of Māori iwi (tribes) and hapū (sub-tribes). It is named after the place in the Bay of Islands where the Treaty was first signed, on 6 February 1840[2]. Te Tiriti is the Māori language version of the document.

The Treaty was not drafted as a constitution or a statute. It was a broad statement of principles upon which the British officials and Māori chiefs made a political compact or covenant to found a nation state and build a government in New Zealand to deal with pressing new circumstances. Like many treaties, it is an exchange of promises between the parties to it.

The Treaty creates a basis for civil government extending over all New Zealanders, on the basis of protections and acknowledgements of Maori rights and interests within that shared citizenry.

New Zealand courts have held that Maori rights might be recognised by the common law, without statutory expression, and a decision maker may be required to with the Treaty rights/interest even where there is no Treaty reference in statute. The courts will generally presume that Parliament intents to legislate in accordance with Treaty Principles.

(a) Treaty Principles

The Waitangi Tribunal have identified a number of core principles that have emerged from Tribunal reports, which have been applied to the varying circumstances raised by the claims. These principles are often derived not just from the strict terms of the Treaty’s two texts, but also from the surrounding circumstances in which the Treaty agreement was entered into. These principles include but are not limited to: Partnership, Reciprocity, Autonomy, Active protection, Options, Mutual benefit, Equity, Equal treatment and Redress[3].

Three principles commonly recognised by government and first outlined in the Royal Commission on Social Policy (1988) are:

- Partnership: interactions between the Treaty partners must be based on mutual good faith, cooperation, tolerance, honesty and respect

- Participation: this principle secures active and equitable participation by tangata whenua

- Protection: government must protect whakapapa, cultural practices and taonga, including protocols, customs and language.

These three principles cover the need for: Co-Governance, Co-Design and Co-Innovation. These principles should form the basis of an explicit Te Tiriti/Treaty of Waitangi clause for any government initiated and or procured Artificial Intelligence Systems and or Algorithms. Government agencies should refer to “Te Arawhiti – Treaty of Waitangi Guidance” paper for further details.

(e) Proposed Guiding Principles

The following guiding principles were extracted and modified to be Treaty compliant from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ethical guidelines (The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies 2012).

- Consultation, negotiation and free and informed consent are the foundations for systems with Māori Data

Government must accept a degree of Māori community input into and control of the system process. This also recognises the obligation on government to give something back to the community. It is ethical practice in any research on Māori issues to include consultation with those who may be directly affected by the research or research outcomes whether or not the research involves fieldwork. The same is applicable with digital systems.

- The responsibility for consultation and negotiation is ongoing. Consultation and negotiation are a continuous two-way process.

Ongoing consultation is necessary to ensure free and informed consent for the proposed digital system, and of maintaining that consent. System development should be staged to allow continuing opportunities for consideration of the design build by Māori.

- Consultation and negotiation should achieve mutual understanding about the proposed systems, Data storage, machine learning and algorithms.

Consultation involves an honest exchange of information about aims, methods, and potential outcomes (for all parties). Consultation should not be considered as merely an opportunity for system designers to tell Māori what they may want. Being properly and fully informed about the aims and methods of a digital system, its implications and potential outcomes, allows Māori to decide for themselves whether to oppose or to embrace the project.

- Maori knowledge systems and processes must be respected.

Acknowledging and respecting Māori knowledge systems (mātauranga Māori) and processes is not only a matter of courtesy but also recognition that such knowledge can make a significant contribution to the design and implementation process. System owners must respect the cultural property rights of Māori Peoples in relation to knowledge, ideas, cultural expressions and cultural materials (mātauranga Māori).

- The intellectual and cultural property rights of Māori must be respected and preserved.

Māori cultural and intellectual property rights are part of the heritage that exists in the cultural practices, resources and knowledge systems of Māori, and that are passed on in expressing their cultural identity. Māori intellectual property is not static and extends to things that may be created based on that heritage. It is a fundamental principle of research to acknowledge the sources of information and those who have contributed to the research.

- The negotiation of outcomes should include results specific to the needs of Māori.

Among the tangible benefits that Māori should be able to expect from a digital system project is the provision of information in a form that is useful and accessible.

- Negotiation should result in a formal agreement for the conduct of a research project, based on good faith and free and informed consent.

The aim of the negotiation process is to come to a clear understanding, which results in a formal written agreement, about system intentions, methods and potential data that is produced. Good faith negotiations are those that have involved a full and frank disclosure of all available information and that were entered into with an honest view to reaching an agreement. Free and informed consent means that agreement must be obtained free of duress or pressure and fully cognisant of the details, and risks of the proposed research. Informed consent of the people as a group, as well as individuals within that group, is important.

(i) Data is a Taonga – Government Perspective

The Government Chief Data Steward’s Data Strategy and Roadmap for New Zealand December 2018 makes statements that allude the importance of data and refers to Data being a taonga. The roadmap states:

Two Māori values in particular will support a trusted data system: manaakitanga (data users show mutual respect) and Kaitiakitanga (all New Zealanders become the guardians of our taonga by making sure that all data uses are managed in a highly trusted, inclusive, and protected way).

Other statements that reinforce that Data is a taonga recognized by government:

- We envisage a future where data is regarded as an essential part of New Zealand’s infrastructure…

- Our ambition is to unlock the value of data for the benefit of New Zealanders.

- The value of data lies in its use

- The availability of new data sets and sophisticated technologies has enabled new and exciting data uses that continue to transform how individuals see, act and engage with the world.

- Data fuels the digital economy, modernising our way of life and enabling innovation across industries and sectors.

- We are increasingly seeing new uses of data that will impact our world in profound ways in the near future.

- The uptake in new technologies such as cognitive computing and Artificial Intelligence (AI) are enabling new and innovative data uses that continue to transform how individuals see, act and engage with the world.

(o) Data is a Taonga – Te Ao Māori Perspective

Māori Data contains, wairua, mauri and is tapu. Therefore, Māori Data is a Taonga. Māori Data is a property and a commodity and therefore all principles of Te Tiriti are applicable.

United Nations Declaration of Indigenous Rights 2007

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples GA Res 61/295 (2007) is a comprehensive international human rights document on the rights of indigenous peoples. It covers a broad range of rights and freedoms, including the right to self-determination, culture and identity, and rights to education, economic development, religious customs, health and language.

The Declaration was adopted on 13 September 2007 as a non-binding, aspirational declaration of the General Assembly of the United Nations. New Zealand officially endorsed in 2010. In 2019 the New Zealand government undertook a road map to compliance, although not yet creating any binding legal obligations, UNDIR is consistent with and complements the Treaty principles and duties as described in [2.47].

The Declaration records the standards and aspirations of governments and indigenous peoples in achieving harmonious and cooperative relations, pursued in a spirit of partnership and mutual respect.

Its 46 articles cover all areas of human rights and interests as they apply to indigenous peoples.

Key themes include:

- equality and non-discrimination;

- education, information and labour rights;

- rights around lands, territories and resources;

- rights to cultural, religious, spiritual and linguistic identity, and self-determination.

The Declaration’s emphasis on self-determination in arts 3–4 provides international support for the recognition of rangatiratanga in New Zealand. In addition, article 31 of the Declaration imposes a duty on States to assist in the protection of indigenous resources including their “cultural heritage”, “traditional knowledge” and “human and genetic resources”. This aligns with the Treaty’s approach to taonga.

The following clauses (See Appendix) are applicable to Artificial Intelligence, Algorithms, Machine learning, Data and IOT projects and should be weaved either into an explicit Treaty Clause or as a separate clause recognising the UNDIR;

Articles: 1,2,3,4,7,8,11,15,18,19,32,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46

Treaty Recognition Statement

All documentation and systems design should include and strictly follow a Treaty of Waitangi/Te Tiriti clause or similarly named clause that contains the following points and information.

(a) The New Zealand government recognises its Treaty of Waitangi/Te Tiriti obligations and will ensure that all governance and design aspects of any initiated and or procured Artificial Intelligence Systems and Algorithms reflect the principles of The Treaty of Waitangi.

(e) The New Zealand government recognises its Treaty of Waitangi/Te Tiriti obligations and will ensure that all governance and design aspects of any initiated and or procured Artificial Intelligence Systems and Algorithms reflect a Te Ao Māori perspective whether that is physical, mental or spiritual.

(i) Any partnerships with international organisations will have a Treaty exception clause as used with international trade agreements.

(o) The New Zealand government officially recognised the international instrument ‘The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples GA Res 61/295 (2007)’ in 2010. The following declarations, as a minimum will be acknowledged in all governance and design aspects of any initiated and or procured Artificial Intelligence Systems and Algorithms; Sections 1,2,3,4,8,11,13,15,18,19,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46.

Governing a Treaty Clause

All documentation and systems design should have an expert advisory group to review compliance with any New Zealand government initiated and or procured Artificial Intelligence Systems, Data, IOT and Algorithm projects.

Membership should consist of Māori with an understanding of technology, tikanga, Te Tiriti and Indigenous Rights. Consideration to diversity of iwi memberships and professional and community backgrounds is essential to provide a balance.

It is not uncommon for ICT professionals to assume they can learn Māori or that they have a good understanding of the culture from observation. A culture, especially a complex and diverse culture such as Māori cannot be learned from a textbook or by observation. True understanding and appreciation are possible only from first-hand lived experience and immersion in Te Ao Māori.

Māori have continued to maintain customs that they have developed and nurtured for hundreds of generations (Taiuru, K.N. 2020). Therefore, hiring a specialist advisor(s) will be necessary in order to fulfil the basic requirements of these ethical guidelines. Choosing the right people is also necessary. By just saying you have a Māori person on staff, or the board is not acceptable. Any Māori representative should be comfortable with all of the frameworks and principals in these guidelines and have wide networks with Māori organisations and Iwi as a minimum requirement.

Kaupapa Māori Frameworks

The following kaupapa Māori ethical frameworks are deemed suitable for Artificial Intelligence Systems, Algorithms and Big Data. These frameworks have been created by experts, peer reviewed and have been used countless times in research and in projects.

The frameworks are ordered in the same order they should be considered and acted upon. Framework (a) is only applicable to the entire New Zealand government sector. Then Framework (e) will assist your design process to ascertain what areas of Māori culture and beliefs are applicable to your system design. The appropriate ethical guidelines for a specific system can be created at this stage.

Frameworks ‘i’ and ‘u’ are both data related and will ensure treaty compliance and Māori cultural safety issues are recognised and explored.

Framework ‘a’, while it was created for health, if you consider a Te Ao Māori perspective, then data and AI should follow Te Whare Tapa Whā framework.

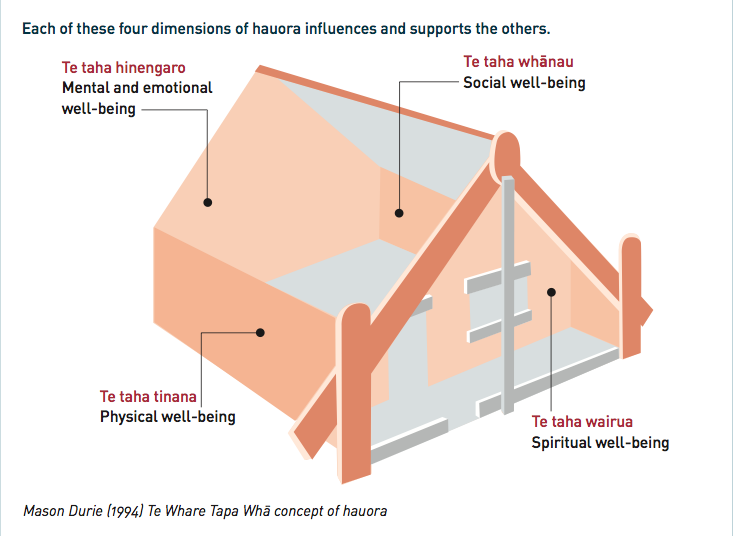

(a) Te Whare Tapa Whā (Durie, M. 1984)

This framework was designed for the health industry but the Te Ao Māori principles relate directly to Māori data. From a Te Ao Māori perspective, when Māori Data is stored, accessed, anonymised, manipulated, transferred, or used it directly impacts the individual’s wairua and mauri; whānau, hapū and Iwi.

The Māori philosophy toward health is underpinned by four dimensions representing the basic beliefs of life. In today’s modern society, Māori need to consider the impacts of colonialism upon all aspects of life, including their genetic data. Māori Genetic Data is genetic data that is held by Māori, extracted from a taonga species or ira tangata, contains or represents any Māori biological material that can trace whakapapa to Ranginui and Papatuanuku and therefore Io (Taiuru, 2019).

Te Taha Hinengaro

This refers to psychological health, with a focus on emotions. It is understood that the mind and body are inseparable, and that communication through emotions is important and more meaningful than the exchange of words.

Te Taha Wairua

This refers to spiritual awareness. It is recognised as the essential requirement for health and well-being. It is believed that without spiritual awareness an individual can be lacking in well-being and therefore more prone to ill health. Wairua explores relationships with the environment, people and heritage.

Te Taha Tinana

This refers to physical health and growth and development as it relates to the body. This focuses on physical well-being and bodily care. Tinana suffers when a person is under emotional stress or is unwell. Pain in different parts of your body is tinana communicating what is going on consciously or unconsciously.

Te Taha Whānau

This is the most fundamental unit of Māori society. Whānau are clusters of individuals descended from a fairly recent ancestor. Whānau may include up to three or four generations, and its importance will vary from one individual to the next. The beliefs, expectations or opinions of the whānau can have a major impact on the career choices that an individual make.

Te Wharenui

This is the symbol used to illustrate these dimensions of well-being. Just as each corner of the house must be strong and balanced to hold its structure, each dimension of well-being must be balanced for health to exist. The wharenui needs the whenua to be healthy and strong to be able to be built upon and to remain strong for inter-generational care.

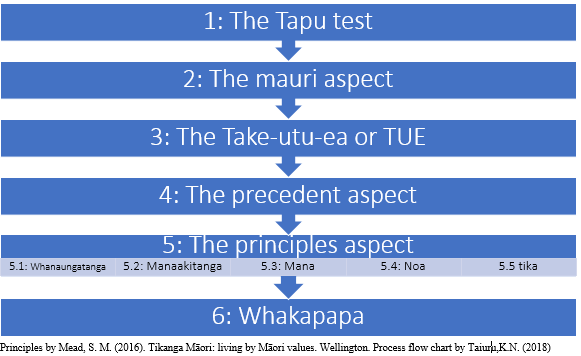

(e) Tikanga Test

(Mead, S. M. (2016. Revis ed.)

A framework using Tikanga Māori and Mātauranga Māori to assess contentious issues to find a Māori position on these issues was developed by Sir Hirini Mead to assist with possible breaches of tapu and to ascertain the risks (Mead, 2016). This test and the proposed frameworks in this document should form the basis for any decision-making process involving Māori data.

Test 1:

The Tapu Aspect – Tapu relates to the sacredness of the person. When evaluating ethical issues, it is important to consider whether there will be a breach of tapu, if there is, will the gain or outcome from the breach be worth it.

Test 2:

The Mauri Aspect – Mauri refers to the life essence of a person or object. In an ethical context, one must consider whether the Mauri of an object or a thing will be compromised and to what extent.

Test 3:

The Take-utu-ea aspect – Take (Issue) Utu (Cost) Ea (Resolution). Take-utu-ea refers to an issue that requires resolution. Once an issue or conflict has been identified, the utu refers to a mutually agreed upon cost or action that must be undertaken to restore the issue and resolve it.

Test 4:

The Precedent aspect. This refers to looking back at previous examples of similar issues that have been resolved in the past. Precedent is used to determine appropriate action for now.

Test 5:

The Principles aspect. This refers to a collection of other Māori principles or values that may enhance and inform an ethical debate.

For the purposes of these guidelines, issues such as those listed in the Community-Up Model: manaakitanga, mana, now, tika and whanaungatanga (Simon, Smith, Cram, University of Auckland. International Research Institute for, & Indigenous, 2001) or the Māori Data Ethical Model (Taiuru, 2018).

(i) Māori Data Sovereignty Guidelines (Te Mana Raraunga, 2018)

01 Rangatiratanga | Authority

1.1 Control. Māori have an inherent right to exercise control over Māori data and Māori data ecosystems. This right includes, but is not limited to, the creation, collection, access, analysis, interpretation, management, security, dissemination, use and reuse of Māori data.

1.2 Jurisdiction. Decisions about the physical and virtual storage of Māori data shall enhance control for current and future generations. Whenever possible, Māori data shall be stored in Aotearoa New Zealand.

1.3 Self-determination. Māori have the right to data that is relevant and empowers sustainable self-determination and effective self-governance.

02 Whakapapa | Relationships

2.1 Context. All data has a whakapapa (genealogy). Accurate metadata should, at minimum, provide information about the provenance of the data, the purpose(s) for its collection, the context of its collection, and the parties involved.

2.2 Data disaggregation. The ability to disaggregate Māori data increases its relevance for Māori communities and iwi. Māori data shall be collected and coded using categories that prioritise Māori needs and aspirations.

2.3 Future use. Current decision-making over data can have long-term consequences, good and bad, for future generations of Māori. A key goal of Māori data governance should be to protect against future harm.

03 Whanaungatanga | Obligations

3.1 Balancing rights. Individuals’ rights (including privacy rights), risks and benefits in relation to data need to be balanced with those of the groups of which they are a part. In some contexts, collective Māori rights will prevail over those of individuals.

3.2 Accountabilities. Individuals and organisations responsible for the creation, collection, analysis, management, access, security or dissemination of Māori data are accountable to the communities, groups and individuals from whom the data derive.

04 Kotahitanga | Collective benefit

4.1 Benefit. Data ecosystems shall be designed and function in ways that enable Māori to derive individual and collective benefit.

4.2 Build capacity. Māori Data Sovereignty requires the development of a Māori workforce to enable the creation, collection, management, security, governance and application of data.

4.3 Connect. Connections between Māori and other Indigenous peoples shall be supported to enable the sharing of strategies, resources and ideas in relation to data, and the attainment of common goals.

05 Manaakitanga | Reciprocity

5.1 Respect. The collection use and interpretation of data shall uphold the dignity of Māori communities, groups and individuals. Data analysis that stigmatises or blames Māori can result in collective and individual harm and should be actively avoided.

5.2 Consent. Free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) * shall underpin the collection and use of all data from or about Māori. Less defined types of consent shall be balanced by stronger governance arrangements.

06 Kaitiakitanga | Guardianship

6.1 Guardianship. Māori data shall be stored and transferred in such a way that it enables and reinforces the capacity of Māori to exercise kaitiakitanga over Māori data.

6.2 Ethics. Tikanga, kawa (protocols) and mātauranga (knowledge) shall underpin the protection, access and use of Māori data.

6.3 Restrictions. Māori shall decide which Māori data shall be controlled (tapu) or open (noa) access.

* https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/ publications/2016/10/free-prior-and-informed-consent-an-indigenous-peoples-right-and-a-good-practice-for-local-communi ties-fao/

(o) Crown engagement with Māori Framework and Engagement Guidelines (Te Arawhiti 2019)

It is the Government’s intent that engagement with Māori and the Māori Crown relationship itself be guided by the following values:

- Partnership – the Crown and Māori will act reasonably, honourably and in good faith towards each other as Treaty partners.

- Participation – the Crown will encourage and make it easier for Māori to more actively participate in the relationship.

- Protection – the Crown will take active, positive steps to ensure that Māori interests are protected.

- Recognition of Cultural Values – the Crown will recognise and provide for Māori perspectives and values.

- Use Mana Enhancing Processes – recognising the process is as important as the end point; the Crown will commit to early engagement and ongoing attention to the relationship.

These values provide a basis for working with Māori to respond to their range of needs, aspirations, rights and interests and provide active partnership with Māori in the design and implementation of processes and outcomes sought.

Engagement Framework can be downloaded from: https://www.tearawhiti.govt.nz/assets/Māori-Crown-Relations-Roopu/451100e49c/Engagement-Framework-1-Oct-18.pdf

Engagement Guidelines can be downloaded from: https://www.tearawhiti.govt.nz/assets/Māori-Crown-Relations-Roopu/6b46d994f8/Engagement-Guidelines-1-Oct-18.pdf

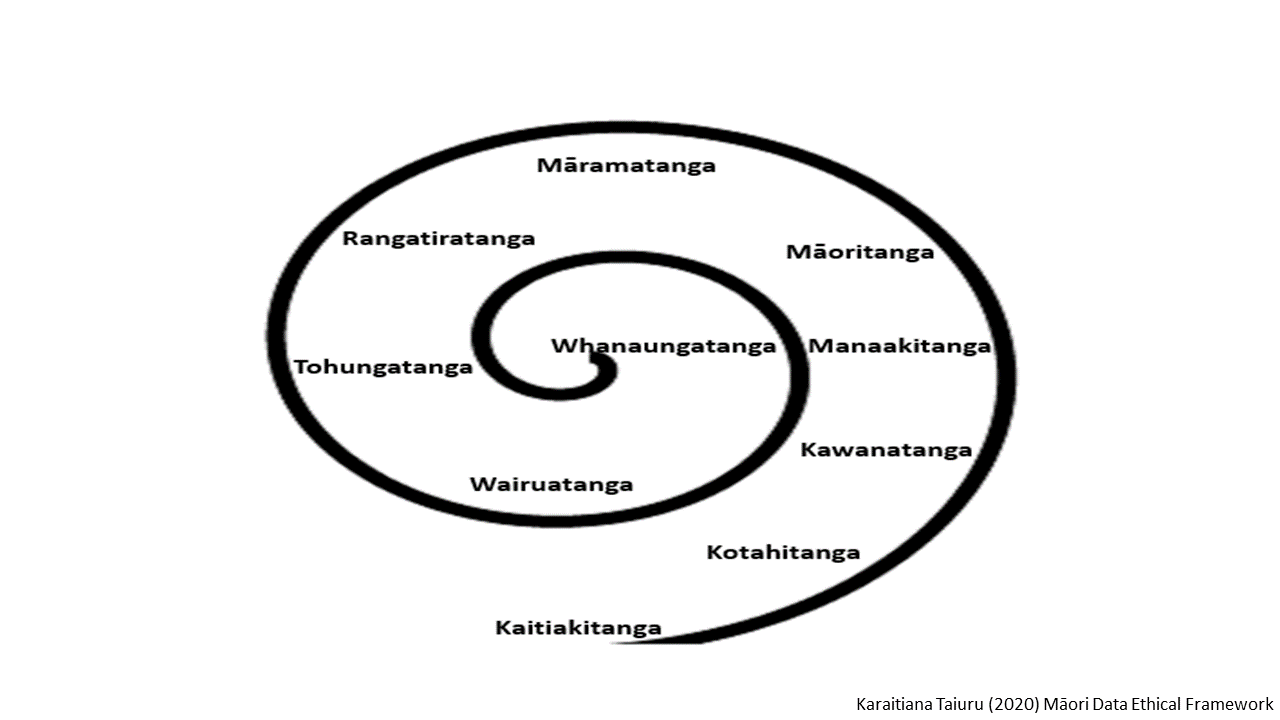

(u) Māori Data Ethical Framework (Taiuru, K. 2020).

To engage with Te Ao Māori; It is recognised that there is not one Māori view due to the impacts of colonisation on Māori and the fact that societal structure is clan based (iwi and hapū).

It is recognised that a Te Ao Māori perspective encases the physical, mental, and spiritual and recognises that everything in the natural world is interconnected including Data.

The following is a Māori Data Ethical Model which uses the Koru pattern as in the Māori Ethics Model (Henare, 1998). These principles recognise and respect a Te Ao Māori view. This framework does not override individual Iwi and corporate Iwi principals (see below for examples).

01 Kaitiakitanga

Guardianship, stewardship, trusteeship, trustee.

This tikanga (customary practice could be applied by ensuring that the system will benefit the majority of Māori and Iwi as opposed to the risk that the objectives of the system are to the detriment of Māori such as the Tohunga Suppression Act and Native Schools Act were. That all data produced, and findings have customary Māori ownership principles applied and that the data is stored on shore. The use of the Tikanga Test could assist in this principle.

02 Kawanatanga

Rule, authority, governorship, province.

This tikanga (customary practice could be applied by recognising the need for Māori representation on the governance, management, and all critical building aspects of a system.

03 Kotahitanga

Unity, togetherness, solidarity, collective action.

This tikanga (customary practice could be applied by not referring to them and us. By recognising that Māori and Iwi interests are also of benefit to all of New Zealand.

04 Manaakitanga

Hospitality, kindness, generosity, support – the process of showing respect, generosity and care for others.

This tikanga (customary practice could be applied by ensuring that there are mutual benefits of a system to both Māori and non Māori. When in doubt about risks versus benefits to Māori, the Tikanga Test could be applied.

05 Māoritanga

Explanation, meaning.

This tikanga (customary practice could be applied by ensuring that there is full disclosure of all algorithms, data, intended and future outcomes of the system are discussed and are explained in a manner that the Māori audience will understand. The use of plain English. When in doubt about risks versus benefits to Māori, the Tikanga Test could be applied.

06 Māramatanga

Enlightenment, insight, understanding, light, meaning, significance

This tikanga (customary practice could be applied by seeking Māori and Iwi insights and information requirements that may be irrelevant to the organisation, but of paramount importance to Māori and Iwi.

07 Rangatiratanga

Knowledge of and practice of the Treaty of Waitangi.

This tikanga (customary practice could be applied by ensuring that a set of Māori ethical guidelines are created, and an explicit Te Tiriti/Treaty clause is included and abided by.

08 Tohungatanga

Expertise, competence, proficiency.

This tikanga (customary practice could be applied by ensuring that a thorough recruitment process is undertaken to contract expert Māori advisors with the relevant skills in Te Ao Māori and the applicable technologies to write, design and implement appropriate Māori ethics.

09 Wairuatanga

Spirituality.

This tikanga (customary practice could be applied by recognising that Data is a taonga what contains wairua and mauri, regardless of if from a western perspective the data is anonymised. Then applying the kaupapa Māori framework Te Whare Tapa Whā to ensure the Wairuatanga of the people in the data are spiritually protected. When in doubt about risks versus benefits to Māori, the Tikanga Test could be applied.

10 Whanaungatanga

Relationship, kinship, sense of family connection – a relationship through shared experiences and working together which provides people with a sense of belonging. A close familial, friendship or reciprocal relationship.

This tikanga (customary practice could be applied by recognising that individual, whānau, hapū and Iwi rights (including legal and moral), risks and benefits are discussed and considered at each step of the life cycle of a systems design. When in doubt about risks versus benefits to Māori, the Tikanga Test could be applied.

(ā) Iwi Corporates

Increasingly in a post treaty settlement era, are Iwi corporates who are also New Zealand government Treaty Partners. Iwi corporates such as Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu and Waikato Tainui. Each iwi corporate as with any corporate have their own set of values and mission statements that may override traditional Māori values. The corporate values and visions may not necessarily be the same with their hapū and marae. But if dealing with Iwi corporate data, the iwi corporate values should take priority.

To ascertain the iwi corporate structure and governance documentation is the same as you would with any corporate structure.

Below are three Iwi corporates who have published Annual Reports and web sites as an example of how diverse an Iwi corporate ethics may be.

Some Iwi corporates are members of the Iwi Chairs Forum, another Iwi based Treaty Partner who also have their own set of values: Rangatiratanga; Whanaungatanga; Manaakitanga; Kaitiakitanga and Tikanga.

Ngāti Kahungunu [4]

The mission or purpose states the reason for the existence of Ngāti Kahungunu Iwi Incorporated “To enhance the mana and wellbeing of Ngāti Kahungunu.” This will be achieved by empowering the iwi to achieve success at the levels of whanau, hapū, Taiwhenua and Taura here. Iwi will determine what success is from its own goals and aspirations.

These guiding principles set the boundaries within which we will work and are not to be compromised for financial gain or short-term expediency.

Te Tūhonohonotanga o Kahungunu – Tapestry of whakapapa that makes us who we are today

Te Hononga Māreikura o Takitimu – How we relate to other iwi / waka

Te Kotahitanga – League of peoples

Te Whakaputanga o te Ao – Declaration of independence

Te Tiriti o Waitangi – Joint venture with Crown

Kanohi ki te kanohi – “Face to face”

Pakihiwi ki te pakihiwi – “Shoulder to shoulder” ~ How we do things

Tino Rangatiratanga – begins with self, continues through the whānau, the hapū and the iwi.

- Controlling our own resources

- Making our own decisions

- Determining our own outcomes

- Owning the consequences of our decisions

- Tū whakahīhī ~ assertive, confident, standing tall and strong

- Independent and contributing to our society

- Government boundaries align to Iwi boundary

Ngāti Rārua [5]

Mission is to have a vibrant Ngāti Rārua culture, economy and society by the year 2040. We will achieve this with our focus on three pillars, a brief outline of this is below.

Hononga: Our Social Strategy

Tikanga:

Manaakitanga – looking after each other

Rangatiratanga – practising and advocating leadership

Whanaungatanga – creating a sense of family and acting as a family

Looking forward:

Engaging more whānau

Knowing ‘us’ best

Investing in an iwi database

Social networking

Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu [6]

Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu promote six tribal values and one tribal vision that form Ngāi Tahu values. The Te Rūnanga Group are also guided by these same values and vision, but with reflected behaviour being slightly more detailed than for iwi members.

The Ngāi Tahu vision is:

Mō tātou, ā, mō kā uri, ā muri ake nei

For us and our children after us.

This serves as a reminder that the current generation’s role is to protect, nurture and make better our people and resources for the next generation. My research does this by identifying an unrecognised issue and resource that will have negative impacts on our people not only now but for generations to come if solutions are not identified now.

The six iwi values are outlined below. Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu definitions do vary to Barlow’s and Mead’s definitions

- Whanaungatanga (family) We will respect, foster and maintain important relationships within the organisation, within the iwi and within the community.

- Manaakitanga (looking after our people) We will pay respect to each other, to iwi members and to all others in accordance with our tikanga (customs).

- Tohungatanga (expertise) We will pursue knowledge and ideas that will strengthen and grow Ngāi Tahu and our community.

- Kaitiakitanga (stewardship) We will work actively to protect the people, environment, knowledge, culture, language and resources important to Ngāi Tahu for future generations.

- Tikanga (appropriate action) We will strive to ensure that the tikanga of Ngāi Tahu is actioned and acknowledged in all of our outcomes.

- Rangatiratanga (leadership) We will strive to maintain a high degree of personal integrity and ethical behaviour in all actions and decisions we make.

In addition to these values, the corporate group has further interpreted them.

Manaakitanga (responsibility) Reflected in the following behaviours:

Tautoko

- Sharing time, knowledge and expertise

- Provides support to others

- Dedicates time to others

- Proactively coaches’ others

Manaaki

- Engages with others in a respectful manner

- Demonstrates the importance of relationships

- Engages others where guidance from others where necessary

Rangatiratanga (leadership). Reflected in the following behaviours:

Self-Awareness

- Builds rapport with ease

- Demonstrates the ability to connect with people at all levels

- Demonstrates empathy

Integrity

- Demonstrates open and honest communication

- Demonstrates fairness

- Acts with integrity and puts benefits of the tribe before own agenda

Whanaungatanga (relationships). Reflected in the following behaviours:

- Collaboration

- Works effectively within a team environment and across the Group

- Actively shares ideas

- Encourages others

Engagement

- Proactively seeks to extend networks within the wider iwi

- Takes steps to ensure is well informed of issues /initiatives within the tribe

Tikanga (integrity). Reflected in the following behaviours:

Tikanga

- Demonstrates a desire to embrace te reo and tikanga

- Actively participates in tribal forums where appropriate

Dedication

- Demonstrates reliability

- Consistently delivers regardless of barriers

- Effectively prioritises

Tohungatanga (professionalism). Reflected in the following behaviours:

Strive for Excellence

- Serves as a role model for others

- Sets goals to achieve high performance, encourages others to aspire to that level

- Delivers work to exceptional quality

Continuous Learning

- Is proactive in seeking learning opportunities

- May teach others in a formal context

- Invests personal time in additional study

Kaitiakitanga (commitment). Reflected in the following behaviours:

- Resourcefulness

- Demonstrates consistent approach to careful expenditure of spending pūtea

- Looks for sustainable solutions when dealing with providers/suppliers

Innovation

- Regularly thinks outside the square

- Demonstrates the ability to turn ideas into reality

- Contributes novel ideas

Waikato Tainui [7]

Waikato Tainui have the following principles: Whakaiti – Humility, Whakapono – Trust and Faith, Aroha – Love and Respect, Rangimaarie – Peace and Calm, Manaakitanga – Caring, Kotahitanga – Unity, and Mahi tahi – Collaboration.

In addition to these principles is their 2050 vision statement. Whakatupuranga Waikato-Tainui 2050 is the blueprint for cultural, social and economic advancement for Waikato-Tainui people. It is a long-term development approach to building the capacity of Waikato-Tainui Marae, hapū, and Iwi. The goals and objectives from the blue print are: Hapori; Kaupapa; Mahi; Tonu; Taiao; Whai Rawa.

Glossary

This is a small list of definitions that are likely to be used with digital systems and designs and are applicable directly to this document. Some are specifically applicable to Māori and should be fully understood.

Artificial Intelligence

This document was created for the intended definitions of AI. These definitions are largely taken from the University of Helsinki (unless otherwise stated) Elements of AI free online course[8].

- AI includes autonomous systems such as driverless cars, delivery robots, flying drones, and autonomous ships.

- Content recommendations that use algorithms to determine the content that you see, such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and other social media content; online advertisements; music recommendations on Spotify; movie recommendations on Netflix, HBO, and other streaming services. Many online publishers such as newspapers’ and broadcasting companies’ websites as well as search engines such as Google who personalize the content they offer.

- Image and video processing systems including organizing your photos according to people, automatic tagging on social media, and passport control. Systems to generate or alter visual content. Examples already in use today include style transfer, by which you can adapt your personal photos to look like they were painted by Vincent van Gogh, and computer generated characters in motion pictures such as Avatar, the Lord of the Rings, and popular Pixar animations where the animated characters replicate gestures made by real human actors. Similar techniques can be used to recognize other cars and obstacles around an autonomous car, or to estimate wildlife populations, just to name a few examples.

- A system that has the ability to improve performance by learning from experience.

- Machine learning can be said to be a subfield of AI, which itself is a subfield of computer science (such categories are often somewhat imprecise, and some parts of machine learning could be equally well or better belong to statistics). Machine learning enables AI solutions that are adaptive. A concise definition can be given as “Systems that improve their performance in a given task with more and more experience or data.”

- Deep learning is a subfield of machine learning, which itself is a subfield of AI, which itself is a subfield of computer science.

- Data science is a recent umbrella term (term that covers several subdisciplines) that includes machine learning and statistics, certain aspects of computer science including algorithms, data storage, and web application development. Data science is also a practical discipline that requires understanding of the domain in which it is applied in, for example, business or science: its purpose (what “added value” means), basic assumptions, and constraints. Data science solutions often involve at least a pinch of AI (but usually not as much as one would expect from the headlines).

- Robotics means building and programming robots so that they can operate in complex, real-world scenarios. In a way, robotics is the ultimate challenge of AI since it requires a combination of virtually all areas of AI. For example:

- Computer vision and speech recognition for sensing the environment

- Natural language processing, information retrieval, and reasoning under uncertainty for processing instructions and predicting consequences of potential actions

- Cognitive modelling and affective computing (systems that respond to expressions of human feelings or that mimic feelings) for interacting and working together with humans

- Many of the robotics-related AI problems are best approached by machine learning, which makes machine learning a central branch of AI for robotics.

Atamai Iahiko

A Māori word for Artificial intelligence (AI) used by the AI Forum. Epistemology of the translation is: Atamai: intelligent; Iahiko: electrical current.

Cyber sovereignty

Cyber sovereignty is a phrase used in the field of Internet governance to describe governments’ desire to exercise control over the Internet within their own borders, including political, economic, cultural and technological activities (Schneier, B. 2016).

Data

Data (singular datum) are individual units of information (Shannon, 1948). A datum describes a single quality or quantity of some object or phenomenon. Although the terms “data” and “information” are often used interchangeably, these terms have distinct meanings. In popular publications, data is sometimes said to be transformed into information when it is viewed in context or in post-analysis [9].

The online Merriam Webster Dictionary defines data as: 1. factual information (such as measurements or statistics) used as a basis for reasoning, 2. discussion, or calculation; information in digital form that can be transmitted or processed; 3. information output by a sensing device or organ that includes both useful and irrelevant or redundant information and must be processed to be meaningful [10]

Data Sovereignty

Data Sovereignty typically refers to the understanding that data is subject to the laws of the nation within which it is stored.

Note: It should be noted that if Māori data is being stored in New Zealand, then the origins of the company must be disclosed. Subsidiaries of U.S. owned corporations are subject to U.S. laws including The USA PATRIOT Act of 2001, and the US PATRIOT Improvement and Reauthorization Act of 2005. These laws permit U.S. government agencies to access any information stored within the U.S. legal jurisdiction without your permission or notification to you.

Digital Colonisation

Digital Colonisation is another ethical consideration for any digital project, especially for Artificial Intelligence and Algorithms.

Digital colonialism deals with the ethics of digitizing Indigenous data and information without fully informed consent.

Digital colonialism is the new deployment of a quasi-imperial power over a vast number of people, without their explicit consent, manifested in rules, designs, languages, cultures and belief systems by a vastly dominant power (Renata Avila, 2017). A new form of imperialism by technology conglomerates for commercial gains; academics and researchers to advance science, technology and research (Taiuru, K. 2017).

Data colonialism is an emerging order for the appropriation of human life so that data can be continuously extracted from it for profit (Mejias, 2019).

The following as individual or partial criterion or as a complete criteria constitute a definition of digital colonialism, therefore potentially breaching Te Tiriti (Taiuru, K. 2015).

- A dominant culture enforcing its power and influence onto a minority culture to digitize knowledge that is traditionally reserved for different levels of a hierarchical closed society, or information that was published with the sole intent of remaining in the one format such as radio or print.

- A blatant disregard for the ownership of the data and the digitized format, nor the dissemination.

- Digital data that becomes the topic of data sovereignty.

- Digital and Knowledge workers who consult Indigenous Peoples to digitise their content and then digitise the content, but who fail to explain the power of technology and the risks including losing all Intellectual Property Rights.

- Conglomerates and government who use their influence to digitize data without consultation.

- N/A

- Digital access where an ethnic minority are the majority digital divide stakeholders; often while their knowledge and resources are being digitised.

- N/A

- Commercial entities paying translators to create new terminology for software and systems, then claiming ownership of the new terminology.

- Manipulation of search engine results to hide or change Traditional Knowledge.

Digital Sovereignty

In Europe, the term Digital Sovereignty is used to represent the western perspectives of ownership. Digital Sovereignty encompasses the idea that users, being citizens or companies, have control over their data (Amaro,S. 2019)

Hātepe

A Māori word for Algorithm. No epistemology is available to the author. The word was sourced from Te reo pāngarau (New Zealand. Learning & New Zealand. Ministry of, 1995).

Hātepe Papatono

A Māori word for Algorithm (Taiuru, K. 2016).

Hinengaro hori

The Māori word for Artificial intelligence (AI). Epistemology of the translation is:

Hinengaro: mind, thought, intellect, consciousness, awareness; Hori: artificial. Translated by Māori Language Interpreter Ian Cormack.

Indigenous Data Sovereignty

Indigenous Data Sovereignty perceives data as subject to the laws, customary rights and treaties of the nation or Indigenous Peoples from which it is collected.

The concept of data sovereignty, is linked with Indigenous peoples’ right to maintain, control, protect and develop their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions, as well as their right to maintain, control, protect and develop their intellectual property over these (Kukutai & Taylor, 2016).

Kaupapa whakamarama

A Māori word for Algorithm (Ryan, 2012).

Māori Data

Māori Data is data that is held by Māori, made by Māori or contains any Māori content or association to Māori including biological. Māori biological Data is data that is held by Māori, extracted from a taonga species, contains or represents any Māori biological material that has whakapapa to Ranginui and Papatūānuku and Io, whether it is still in its biological state or has been altered including digitisation (Taiuru, K. 2020).

Māori Data Sovereignty

Māori Data Sovereignty recognises that Māori data should be subject to Māori governance and supports tribal sovereignty and the realisation of Māori and Iwi aspirations. Māori data sovereignty recognises the principles of Te Tiriti.

Network Sovereignty

Network sovereignty is the effort of a governing entity, such as a state, to create boundaries on a network and then exert a form of control, often in the form of law enforcement over such boundaries (Obar, J. 2013).

Nuka rorohiko

A Māori word for Algorithm (Taiuru, K. 2016).

Robot

This definition is taken from the University of Helsinki Elements of AI free online course[11].

In brief, a robot is a machine comprising sensors (which sense the environment) and actuators (which act on the environment) that can be programmed to perform sequences of actions. People used to science-fictional depictions of robots will usually think of humanoid machines walking with an awkward gait and speaking in a metallic monotone. Most real-world robots currently in use look very different as they are designed according to the application. Most applications would not benefit from the robot having human shape, just like we don’t have humanoid robots to do our dishwashing but machines in which we place the dishes to be washed by jets of water.

It may not be obvious at first sight, but any kind of vehicles that have at least some level of autonomy and include sensors and actuators are also counted as robotics. On the other hand, software-based solutions such as a customer service chatbot, even if they are sometimes called `software robots´, aren´t counted as (real) robotics.

Further Resources

This small list of further reading will assist in understanding Māori culture and digital systems.

(a) Artificial Intelligence and Robotics

- Submission on Government algorithm transparency and accountability. Karaitiana Taiuru. December 9, 2019 https://www.taiuru.co.nz/submission-on-government-algorithm-transparency-and-accountability/

- Treaty Clause Required for NZ Government AI Systems and Algorithms. November 11, 2019. Karaitiana Taiuru. https://www.taiuru.co.nz/treaty-clause-required-nz-government-ai-systems-and-algorithms/

- Māori ethics associated with AI systems architecture. Karaitiana Taiuru. https://www.taiuru.co.nz/maori-ethics-associated-with-ai-systems-architecture/

- Māori cultural considerations with Artificial Intelligence and Robotics. Karaitiana Taiuru. June 21, 2019 https://www.taiuru.co.nz/ai-robotics-maori-cultural-considerations/

- Māori Ethical considerations with Artificial Intelligence Systems. Karaitiana Taiuru. October 2017 https://www.taiuru.co.nz/maori-ethical-considerations-with-artificial-intelligence-system/

(e) Data

- Māori Data Sovereignty Rights for Well Being. Karaitiana Taiuru. September 25, 2019. https://www.taiuru.co.nz/maori-data-sovereignty-rights-for-well-being/

- Data is a Taonga. A customary Māori perspective. December 19, 2018. . Karaitiana Taiuru. https://www.taiuru.co.nz/data-is-a-taonga/

- Indigenous Data Sovereignty: Toward an agenda. 2016. Kukutai, T., & Taylor, J. ANU Press.

- Māori Data Sovereignty: Utopia or feasible? April 9, 2016. Karaitiana Taiuru. https://www.taiuru.co.nz/maori-data-sovereignty-utopia-feasible/

- Māori Data Sovereignty: A definition. Karaitiana Taiuru. April 6, 2016. https://www.taiuru.co.nz/maori-data-sovereignty-definition/

(i) Indigenous

- Indigenous Protocol and Artificial Intelligence Working Group http://www.indigenous-ai.net/

Appendices

Appendix A: Te reo Māori version of the Treaty

Appendix E: English version of The Treaty

Appendix I Translation of the te reo Māori text

Appendix O United Nations Declaration of Indigenous Rights 2007

Appendix A: Te reo Māori version of the Treaty

The following version of the te reo Māori text of the Treaty of Waitangi is taken from the first schedule to the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975.

Ko Wikitoria, te Kuini o Ingarani, i tana mahara atawai ki nga Rangatira me nga Hapu o Nu Tirani i tana hiahia hoki kia tohungia ki a ratou o ratou rangatiratanga, me to ratou wenua, a kia mau tonu hoki te Rongo ki a ratou me te Atanoho hoki kua wakaaro ia he mea tika kia tukua mai tetahi Rangatira hei kai wakarite ki nga Tangata maori o Nu Tirani-kia wakaaetia e nga Rangatira maori te Kawanatanga o te Kuini ki nga wahikatoa o te Wenua nei me nga Motu-na te mea hoki he tokomaha ke nga tangata o tona Iwi Kua noho ki tenei wenua, a e haere mai nei.

Na ko te Kuini e hiahia ana kia wakaritea te Kawanatanga kia kaua ai nga kino e puta mai ki te tangata Maori ki te Pakeha e noho ture kore ana.

Na, kua pai te Kuini kia tukua a hau a Wiremu Hopihona he Kapitana i te Roiara Nawi hei Kawana mo nga wahi katoa o Nu Tirani e tukua aianei, amua atu ki te Kuini e mea atu ana ia ki nga Rangatira o te wakaminenga o nga hapu o Nu Tirani me era Rangatira atu enei ture ka korerotia nei.

Ko te Tuatahi

Ko nga Rangatira o te Wakaminenga me nga Rangatira katoa hoki ki hai i uru ki taua wakaminenga ka tuku rawa atu ki te Kuini o Ingarani ake tonu atu-te Kawanatanga katoa o o ratou wenua.

Ko te Tuarua

Ko te Kuini o Ingarani ka wakarite ka wakaae ki nga Rangatira ki nga hapu-ki nga tangata katoa o Nu Tirani te tino rangatiratanga o o ratou wenua o ratou kainga me o ratou taonga katoa. Otiia ko nga Rangatira o te Wakaminenga me nga Rangatira katoa atu ka tuku ki te Kuini te hokonga o era wahi wenua e pai ai te tangata nona te Wenua-ki te ritenga o te utu e wakaritea ai e ratou ko te kai hoko e meatia nei e te Kuini hei kai hoko mona.

Ko te Tuatoru

Hei wakaritenga mai hoki tenei mo te wakaaetanga ki te Kawanatanga o te Kuini-Ka tiakina e te Kuini o Ingarani nga tangata maori katoa o Nu Tirani ka tukua ki a ratou nga tikanga katoa rite tahi ki ana mea ki nga tangata o Ingarani.

(Signed) William Hobson,

Consul and Lieutenant-Governor.

Na ko matou ko nga Rangatira o te Wakaminenga o nga hapu o Nu Tirani ka huihui nei ki Waitangi ko matou hoki ko nga Rangatira o Nu Tirani ka kite nei i te ritenga o enei kupu, ka tangohia ka wakaaetia katoatia e matou, koia ka tohungia ai o matou ingoa o matou tohu.

Ka meatia tenei ki Waitangi i te ono o nga ra o Pepueri i te tau kotahi mano, e waru rau e wa te kau o to tatou Ariki.

Ko nga Rangatira o te wakaminenga.

Appendix E: English version of The Treaty

The following version of the English text of the Treaty of Waitangi is taken from the first schedule to the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975.

Preamble