Deepfakes are forms of digitally altered media — including photos, videos and audio clips — that seem to depict a real person. They are created by training an AI system on real clips featuring a person, and then using that AI system to generate realistic (yet inauthentic) new media. Deepfake use is becoming more common. TVNZ have a great video introduction of Deep Fakes.

The ease of simplicity of creating deep fakes with AI is ever increasingly being used by non technical people and alarmingly among youth in New Zealand.

This use of AI technology when used by criminals can be dangerous and manipulative. Without proper guidelines and frameworks in place, more whānau, businesses, land trusts, marae, iwi, hapū and any organisations risk falling victim to AI scams like deepfakes.

Statistically Māori are more likely to be victims of all forms of online fraud and online abuses. Recently, scammers have been targeting online tangi of recently deceased Māori, fraudulent pay for online Kapa Haka competitions. There are also several public and private cases of innocent Māori women where scammers have taken their image from business web sites and social media, and applied their faces to a porn web site adverts and other adult entertainment advertising.

Māori and other cultures are also predominantly victims of image theft of individual’s personal faces, in particular for Māori (those with facial moko) that are then used in art and photo shopped with racist diatribes and on sold as art.

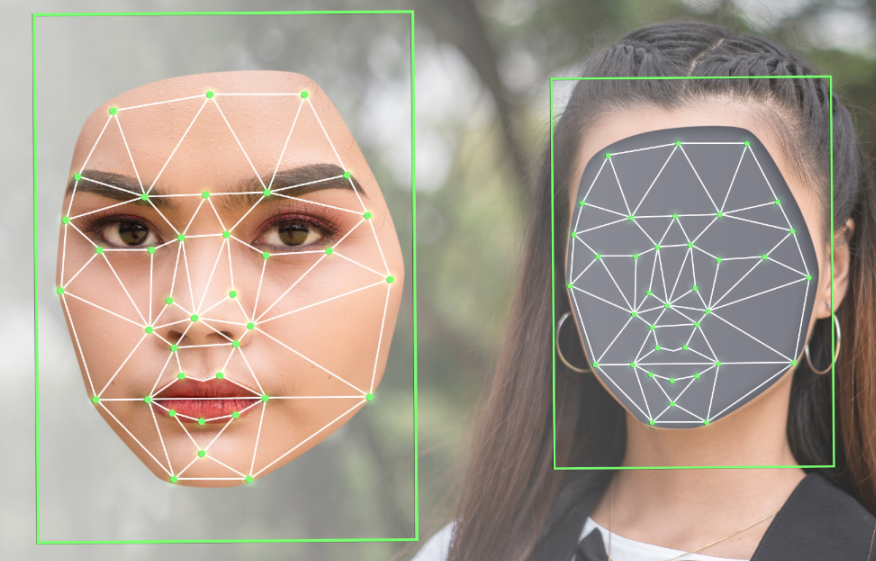

Examples of Deepfakes

Security commenters in America are particularly concerned that their upcoming elections will be bombarded with deep fakes that could influence the election. I would suggest that New Zealand should closely follow America’s concerns, and as Māori, we should be highly aware of developments, in particular Māori politicians who are likely to be targets of such online actions.

Previously, the New Zealand National Party had one image that was a deep fake and then withdrew it after admitting so. More recently, Donald Trump in his presidential campaign used deep fakes in images of himself surrounded by Black voters despite having very little support of Black voters.

Recently a Hong Kong-based company employees were duped into thinking that they were talking to their UK-based chief financial officer who asked them to wire out US $25.6 million. The staff were initially suspicious, but then completed the transfer believing the video call was legit.

Older examples of Deep Fakes that reached international media include Morgan Freeman, Barack Obama calling Donald Trump a “complete dipshit”, Mark Zuckerberg bragging about having “total control of billions of people’s stolen data” and Jon Snow’s moving apology for the dismal ending to Game of Thrones.

While these may be humorous for some, there are certainly criminal activities such as deep fake porn where innocent people have their faces added to pornographic images and videos. In many cases, the victims never know until someone point sit out to them. Another popular case was the celebrity Taylor Swift who was a victim of deep fake porn that attracted international attention.

Cybercriminals have also targeted individuals with ‘spear phishing’ attacks that use deepfakes. A common approach is to deceive a person’s family members and friends by using a voice clone to impersonate someone in a phone call and ask for funds to be transferred to a third-party account. Last year, a survey by McAfee found that 70% of surveyed people were not confident that they could distinguish between people and their voice clones and that nearly half of surveyed people would respond to requests for funds if the family member or friend making the call claimed to have been robbed or in a car accident.

Another scam that will likely impact those who are seeking romance is online romantic scams where individuals engage in video calls with someone who is deep faking the video. The same technology could be used as someone pretending to be a whānau member, kaumātua, leader or anyone from the marae.

Voice Cloning

Another form of deep fake technology is voice cloning. Voice cloning is used to overcome voice authentication by using voice clones of people to impersonate users and gain access to their banks and other private data. There are multiple international examples of family members believing that they are speaking to a family member who is requesting money, but it is a criminal using voice cloning. Māori are vulnerable to voice cloning by criminals pretending to be whānau, a workplace manager, kaumātua etc. While this could be easily avoided, in New Zealand this could be used for automated services such as IRD.

In New Zealand, we do not have laws preventing deepfakes of images and videos. But the voice cloning may be an offence under Section 240 of the Crimes Act 1961 No 43 (as at 13 April 2023) but this has not been used for other instances of online impersonation for hate crimes. In February this year, the Federal Communications Commission ruled that phone calls using AI-generated human voices are illegal unless made with prior express consent of the called party. The Federal Trade Commission also finalized a rule prohibiting AI impersonation of government organizations and businesses and proposed a similar rule prohibiting AI impersonation of individuals. This adds to a growing list of legal and regulatory measures being put in place around the world to combat deepfakes.

Tips

To protect whānau and hapū, iwi, marae, staff and others against brand reputation against deepfakes, the following should be considered:

- Many Māori know their own pepeha, whakapapa and subtle names and histories about their marae and geographic places. Use that knowledge to check the person you are talking to is indeed the real person.

- AI can speak Māori already, but not that well and it is very generalised language. If you are a Māori language speaker, you will likely be able to detect very quickly if the other person does not understand you or uses poor language skills. Likewise, the usage of whakataukī and mita is not known by AI.

- Implement cultural best practices with online hui such as whakawhanaungatanga or karakia

- Be aware of what mātauranga and te reo Māori AI already knows. For example, if someone in your iwi has used AI for your iwi history, you could be at more risk than other iwi.

- Educate whānau and staff on an ongoing basis, both about AI-enabled scams and, more generally, about new AI capabilities and their risks.

- Organisation IT policies around phishing guidance should include deepfake threats. Many companies have already educated employees about phishing emails and urged caution when receiving suspicious requests via unsolicited emails. Such phishing guidance should incorporate AI deepfake scams and note that it may use not just text and email, but also video, images and audio.

- Consider the impacts of deepfakes on company assets, like logos, advertising characters and advertising campaigns. Such company assets can easily be replicated using deepfakes and spread quickly via social media and other internet channels. Consider how your company will mitigate these risks and educate stakeholders.

- Use watermarks on images and consider not photographing sensitive objects. Perhaps consult tikanga experts and adapt traditional tikanga with images.

- Be aware of certain nuances such as a person wearing a taonga that they would normally only wear at say tangi, but question if that person is wearing that taonga in an online meeting.

- Sometimes, the deepfake image may glitch, pixelate, blur or you will see some other form of interference

- A common sign of a deep fake is if the person in the image is not moving or moving very little.

- Like foreign films that have the English language over it, the actors lips move at different times and ways than the spoken word.

Conclusion

Combining the alarming statistics of online fraud and online abuse of Māori and looking at international trends, the next likely wave of online scams against Māori will likely be ‘Deep Fakes”. It will not just be international and national politics, nor just famous people but anyone could be a victim of a deep fake. Iwi, hapū, whenua and any Māori elections could be targeted by Māori with interests in Māori organisations.

Te Ao Māori organisations such as businesses, land trusts, marae, iwi, hapū and any organisations responsible for finances must also be weary of deep fake videos impersonating managers to fraudulently have money transferred, sign over assets or even making decisions that may not be appropriate.

Deepfakes are not just a cybersecurity concern but are a complex and emerging phenomena with broader repercussions that have significant and real impacts on innocent and often unbeknown to individuals, whānau, iwi, hapū, marae, organisations and companies. Marae, hapū and others need to consider how to train and implement practices to avoid being a victim of deep fakes and be more proactive in combating this emerging phenomena.

If you are a victim of a deep fake, please contact NetSafe. For organisations you may need to contact CERT NZ or if more serious the Police.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.