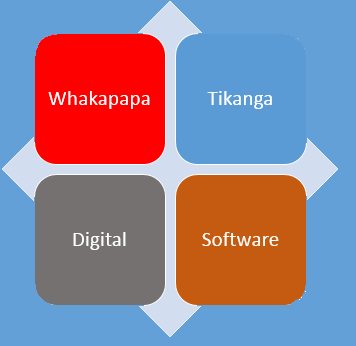

The nature of the web and digital technologies leads Māori ICT organisations, kupu hou creation, Māori related software, web sites and digital tools to by default, ignore whakapapa in the digital world. I have already spoken widely about tikanga in the digital world on my site.

Māori stories from many generations ago remind us of the early explorer Kupe, who he was, his whakapapa, and the many waka that first found Aotearoa New Zealand. Each Iwi have their own stories, and whakapapa about Iwi, places and their names, people, nature and much more.

There are volumes of information about early te reo Māori and history books, letters, publishers, historical photographs and details about artifacts. But there is no where that documents the first Māori owned web site, the first Māori language web site, the first Māori software, major localisation project team members including for projects such as Microsoft and Google, or the pioneers who carved a way into the Internet for Māori to be represented with .iwi.nz, .maori.nz and with macrons.

When computers became accessible to New Zealand homes, companies and governments; when society replaced typewriters for computers, and the world wide web was introduced into our lives, there was a common belief among Māori that such technology was “a Pākehā thing”. Kaumātua around the country personally told me of their dislike of the web and how they feared it would ruin our culture. “What about kanohi ki kanohi” they would say to me. I always disagreed with the kaumātua because we had email that would enhance relationships, and then we were introduced to social media such as Facebook, Skype, Instagram, online video and the many other technologies that assist our people and communities to be more networked and assist ahi kaa, break down barriers to whakama, urbanisation or even living overseas.

By the general nature of the World Wide Web where information flashes past our eyes, we often neglect to know or take notice of the owners and pioneers of information and technology. What is innovative one day can quickly be normalised and the authors forgotten the next day.

For others, they may be silent while others claim their mana and claim that they were in fact the author of achievements. The media often take information at face value and false histories can be quickly re-written.

Often those who are acknowledged are the ones who have made small contributions but are conspicuously always trying to get attention. It has become the norm to acknowledge those and not the true leaders.

The misinformation by self publishers has played on the fact in some cases that it is another area of Māori customs (whakahihi) where the person who made the achievements or was the original creator will not say anything as he/she still has the respect (mana) of their own people and the people who were associated with the truth.

Background

Over the past few months researching and cataloging Māori ICT organisations, compiling the Māori dictionary of ICT and Social Media terms and creating a timeline of Māori software creation of the past two decades has raised many questions about whakapapa in the online world that have not yet been discussed or published. More disturbing is how facts can be quickly changed and then become the new truth, essentially altering whakapapa.

It is/was common to hide and preserve whakapapa so that outsiders could not make claims to mana and land. Yet Māori in the digital area do not have the same concerns.

Once Māori knew who they were, who was associated with the group, Iwi and hapū, tipuna, atua and who created something and the story behind it. No hea te mea, no hea koe were once questions you could reasonably expect a reply to in the offline world.

My new concerns are in addition to the issues of traditional knowledge and ownership that are recognised by Indigenous communities and Peoples all over the world. This is about the anonymous nature of the world wide web that by default ignores tikanga and whakapapa and allows others to claim ownership for nothing other than ego and selfishness. No raupatu, no ahi kaa, no muru are used in todyas digital world to take ownership. Today it is plain cold colonial fraud and whakahihi that plays on cultural values of being whakama and authors and leaders relying on their own mana with their own people.

Māori ICT organisations

Māori ICT organisations are created quickly to meet a need and often can shut down once a goal has been achieved. The organisations are hapū like in structure and objectives but the ICT organisations leave little proof they existed and no whakapapa of membership. For those who do publicise their whakapapa, the nature of the Internet and web leaves little proof of the people or the organisation as web sites are removed or not renewed.

Some of the historical (Internet time) knowledge that I had was from personally knowing the people involved or having been a member of the organisation. Yet there is little or no information online or in any academic material I could source. This makes me question what will happen in ten years time or more. Will we be referenced as Internet ethnographers in 2030?

We do have the national library archives but they are difficult to access and expensive even to access your own information. Data sovereignty issues and Digital Colonialism may seem the demise of the invasive archiving. The web harvest robot also does not include domain names and many free services housed overseas, social media etc.

The power of Māori and non Māori self-publishers has essentially rewritten some aspects of Māori online which the media have reported as true. This in turn has then assisted the self publisher to further manipulate the media and digital whakapapa. It raises another question “Is Wikipedia more authoritive than self published Indigenous knowledge as it is community edited and requires a number of resources to verify information”?

Software

Software authored by Māori has the same digital whakapapa fate. Software and system changes and evolves so quickly it rapidly makes generations of software redundant. Macrons and Māori spellchecking tools are a good example of software that is now by default a part of all new Microsoft Windows systems. He mihi to ReddFish Intergalactic and Greg Ford and the late Akuhata Tangaere for the first publicly available Māori specific software “Te Kete Pūmanawa”.

Websites

There is no official record written about the first Māori owned and authored web site. Again, it is only through association that I know these undisputed facts. I want to acknowledge Kamera Rahara and Ross Himona who between the two of them produced the first Māori owned and authored web sites Internet of which both sites are still in existence today http://www.maori.org.nz and http://maaori.com/rhimona/

Digital images

Digital images whether a photo or a drawing placed on the web or social media quickly become anonymously shared; hundreds, thousands, millions of times or manipulated into memes, pirated and even copyrighted by others.

Bloggers

Blogs are often written on free cloud based platforms such as blogger.com and WordPress.com become digital ghettos when the authors no longer have the time or motivation to keep them updated.

It is not unusual for free online services to cease their services leaving the responsibility of individuals to copy their information. Once it has gone, it has gone forever.

Localisation projects

Some significant localisation projects have occurred over the years for conglomerates and small businesses who have paid contractors to complete a service. In the commercial world their names will not be recorded or well known outside of the team. Often it creates the issue of the word not being widely known to be in existence.

Other translators have completed significant amounts of work for their universities or out of their own passion and in at least one instance someone else took credit for a large amount of work they did not do.

With any localisation project comes the need to create new terminology. The whakapapa of the creation of the new terminology is usually known only by those who created the new words. Some new terminology provides whakapapa of words as seen in Te Matatiki Dictionary produced by Te Taura Whiri.

He mihi tēnei ki a Dr Te Taka Keegan who has made significant contributions to Google Māori, Moodle and Microsoft localisation projects among other initiatives.

Indigenous Domain Names and macrons

Despite the fact that New Zealand’s Internet governing body published a book on the history of the Internet in New Zealand called “Connecting the Clouds – the Internet in New Zealand” there was no mention of .iwi.nz creation or the significant achievement of Māori to have .maori.nz created.

.iwi.nz; In 1994 Ngāi Tahu Iwi suggested to John Faulkner that the creation of .iwi.nz would be beneficial. John then begun the discussion on the Tuia Technical Working Group list .

Don Stoke then discussed it with John, and they agreed that it had sufficient character to be a separate domain, but we were worried about reactions. Don discussed it with his mother (Professor, later Dame, Evelyn Stoke, who was a member of the Waitangi Tribunal), and from that they wrote up a brief guideline for registrations. Then they created the domain, running it alongside govt.nz and mil.nz out of Victoria University.

In 2002 the domain name was to be retired after Aroha Mead had been a temporary moderator. The New Zealand Māori Internet Society was then given moderation responsibility and then soon after Karaitiana Taiuru. A significant amount of re-work to make the policy more accessible to Māori was undertaken. The policy resides at

.maori.nz; was created in 2002 after a successful submission tested for the first time InternetNZ guidelines for creating new domain names. .maori.nz was and still is the world first open Indigenous domain name.

The author was Karaitiana Taiuru who also lead the public campaign and was chair of The New Zealand Māori Internet Society. There were two previous attempts for the creation, one by Ross Himona in 1997 while he was working Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust . The trust wanted to make an Internet presence and use the domain kohanga.ac.nz . At that time the .ac.nz domain was moderated and only available for tertiary level institutions. Upon the Kōhanga Reo National Trust applying for kohanga.ac.nz they were informed by the moderator that the Kōhanga was not an academic institute therefore unable to use .ac.nz. They were also not eligible to use .school.nz which at that time was also moderated. The trust was told that as they were a trust which administers the movement of 750 plus kōhanga reo and a registered charitable trust, therefore should apply for .org.nz.

In that same year a public submission was made available by InternetNZ (previously known as ISOCNZ) for any interested parties to submit feedback about new Second Level Domains. This was an opportunity for Kōhanga to be represented fairly on the web and to apply for .maori.nz to be created. A number of submissions were sent to InternetNZ in support of a new Māori domain “.maori.nz” with no success.

Macrons in domain names; in 2008, after the “Connecting the Clouds – the Internet in New Zealand” publication, the ability to use a macron in all .nz domain names and the creation of .māori.nz was introduced. This technology is called International Domain Name.

The public consultation was begun after Karaitiana Taiuru (this author) lobbied the Domain Name Commissioner to recognise that Māori was an official language of New Zealand and to keep in line with international efforts by ICANN the worlds domain name governing body to recognise non Latin characters in domain names.

During discussions by the working group, it was agreed that .māori.nz would be created, meaning that the worlds fifth Indigenous domain name would be created and that it would automatically go to any .maori.nz address by automatically.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.