A social media wildlife expert called a First Nations version of Steve Irwin drew a large following that The Guardian exposed the account as an AI-generated character. A South African content creator reportedly ran the operation from New Zealand.

Indigenous experts have described the account as AI and digital blackface: modern racial impersonation that simulates identity because it performs well online. The format can amplify bias from training data, invite racialised commentary, and recycle stereotypes about Indigenous Peoples.

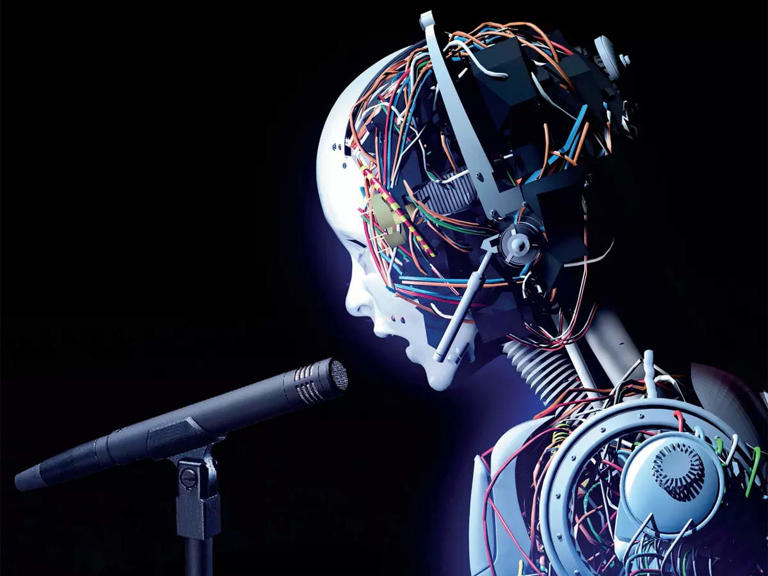

In the generative AI era, AI blackface will rarely look like a crude caricature. It will look like polished positive content – an AI influencer, an AI teacher or an AI community voice designed to look and sound Indigenous enough to earn trust, build a following, and convert attention into money and influence.

Dr Terri Janke, a lawyer specialising in Indigenous cultural and intellectual property, said the images and content looked “remarkable” in their realism. “You think it’s real. I was just scrolling through and I was like, ‘How come I’ve never heard of this guy?’ He’s deadly, he should have his own show,” she said. “Is he the Black Steve Irwin? In his greens or the khakis, he’s a bit like Steve Irwin meets David Attenborough,” she told The Guardian.

For Māori, the equivalent scenario could include a synthetic reo teacher who sounds close enough for beginners while quietly embedding errors and flattening dialectal variation – a new form of colonisation of our reo. It could include a hyper real Māori artist influencer who sells designs without whakapapa or who relies on stolen imagery, maybe a synthetic tikanga expert that corporates and public agencies use as a cheap substitute for real Māori expertise. Or, it could take the form of a digital kaumātua voice that carries the tone of authority but has no mandate, and triggers offensive tikanga breaches.

Online, identity functions like a credential, and this dynamic will intensify through 2026. Viewers assume that if someone looks Māori, sounds Māori, and uses Māori cultural cues, they likely have lived experience, relationships, and iwi/hapū/marae/community accountability. Synthetic identity breaks that link and manufactures credibility while stripping away the obligations that normally come with representation of te ao Māori. It is an extraction model that turns cultural identity into a commodity at the expense of the traditional knowledge holders.

In an election context, the risks escalate. Bad actors can launder legitimacy by using a Māori MP’s and candidates faces, and voices to push political messages. They can micro target and manipulate Māori voters with tailored misinformation about parties, candidates, co governance, Te Tiriti issues, Māori wards, or resource decisions. They can also suppress participation through deep faked scandals, fake official notices (polling changes, eligibility, enrolment deadlines), or coordinated harassment that intimidates Māori candidates and community voices.

The Guardian reporting also raised concerns about how these avatars get made. Creators can assemble features from real faces, often without consent, and the process can flatten and distort culture. For Māori, the risk that someone might scrape and blend real people’s images or voices (including tūpāpaku) into new identities is not an abstract tech issue. We have already seen versions of this behaviour in campaigns linked to advertising agencies, racist online attacks and mockery, and right-wing lobby groups.

Some will argue the fix is simple, just add a disclaimer that it as AI generated. While this is a moral duty for everyone, that approach does not protect Indigenous audiences with AI Black Face. AI disclaimers and labels are not a safeguard. AI expert Professor Toby Walsh warned that the cues people rely on to detect synthetic content are becoming harder to spot.

New Zealand does have mechanisms that may help where individuals suffer harm, including the Harmful Digital Communications Act. However, AI blackface often creates collective cultural and economic harms that sit between privacy, consumer protection, intellectual property, and platform policy. The draft Deep fake Digital Harm and Exploitation Bill, in its current form, needs broader consideration if it is to address this category of harm effectively.

Māori and communities can act now without waiting for government by treating Māori coded content as a high risk category and building simple monitoring and response pathways such as:

- Finding out who runs the account, where they are based, and whether they name real people and affiliations

- Keep whānau, hapū, iwi and Māori organisations on a shared watchlist of suspicious accounts, deep fakes, and recurring narratives

- Capture evidence early, such as screenshots, URLs, timestamps and escalate quickly to platforms, advertisers, and media outlets

- Invest in trusted Māori channels by directing audiences to verified Māori creators, iwi comms, Māori media, and kaupapa led fact checking so that credibility can remain with relevant experts in te ao Māori.