AI Agents are to Māori what Captain Cook and his Endeavour Ship and crew were. If Māori understood the challenges and intergenerational colonisation they were capable of, the historical outcomes would be very different.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) agents are rapidly becoming autonomous actors within social, economic, and governmental systems. For Māori, these agents introduce new forms of technological colonialism that threaten data sovereignty, bias, cultural appropriation, epistemic integrity, and cultural survival.

Drawing on Te Tiriti o Waitangi, Māori Data Sovereignty frameworks, and comparative global standards, this article analyses the systemic and cultural risks posed by AI agents to Māori communities. It identifies six categories of risk: data sovereignty, cultural distortion, epistemic harm, governance failure, economic displacement, and ethical desecration. It then proposes a Tiriti-based model for Māori led AI governance grounded in mana motuhake and kaitiakitanga.

Introduction

AI agents are autonomous digital entities capable of learning, adaptation, and interaction. They are reshaping governance, communication, and knowledge systems. Yet their emergence within colonial states such as Aotearoa New Zealand raises profound issues of power and control. For Māori, the evolution of AI represents not only a technological frontier but also a risk of continuation of colonial encounters mediated through data and code.

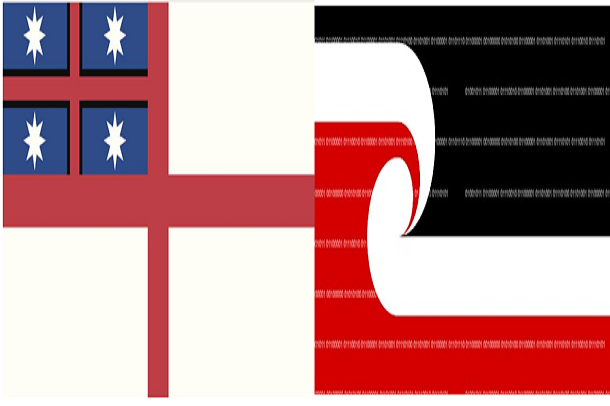

The Treaty relationship between Māori and the Crown provides a constitutional foundation for Māori governance over digital taonga. However, current AI development largely excludes Māori participation and disregards tikanga Māori and Te Tiriti. This raises the question how AI will impact Māori, and how these impacts can be governed using Te Tiriti o Waitangi obligations.

Data Sovereignty and Digital Colonialism

Māori Data Sovereignty is Māori Data Governance. It recognises the principles, structures, accountability mechanisms, legal instruments, and policies through which Māori exercise control over Māori data. It is about both individual and collective over their data.

AI agents routinely breach these rights through unconsented data harvesting, global data sharing, and opaque model architectures. When Māori imagery, language, or genomic data are used to train AI systems, it is often hosted offshore, resulting in a new form of digital extractivism.

These practices undermine mana motuhake and breach Article 2 of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, which guarantees Māori authority over taonga. They replicate colonial hierarchies by placing Māori data under corporate jurisdiction and Western epistemic control.

Cultural and Epistemic Risks

AI systems operationalise knowledge as data, reducing relational and spiritual knowledge systems to tokenised information. For Māori, this can manifest as:

- Cultural distortion: misrepresentation of Māori concepts, reo, tikanga and narratives.

- Epistemic harm: privileging Western rationalism over relational worldviews.

- Desecration of tapu: reproduction of sacred imagery or knowledge in commercial outputs.

When mātauranga Māori is abstracted from its cultural context, it loses its mauri and becomes commodified, creating a breach of Māori cultural protocols that must be balanced.

Governance and Accountability Deficits

Existing AI governance frameworks including but not limited to the OECD AI Principles (2021), NIST AI Risk Management Framework (2023), EU AI Act (2024), ISO 42001 AI Management Standard and the NZ Responsible AI Guidance for the Public Service: GenAI (2025) all lack provisions for Indigenous Peoples authority or collective redress. They frame harm in individualistic terms, ignoring cultural, spiritual, and intergenerational dimensions of damage.

Without explicit Māori oversight, AI systems continue to operate under a presumption of neutrality. These systems encode the values and biases of their developers. Māori peoples remain data subjects, not data governors, perpetuating a structural imbalance in digital power.

Socio-Economic and Structural Risks

AI driven automation risks displacing Māori workers, artists, reo teachers, and educators, replacing community-based expertise with synthetic approximations based on incomplete and bias data. Meanwhile, the Māori economy remains excluded from AI’s value chains due to lack of skilled people, capital, technical infrastructure, and access to training data. This deepens algorithmic dependency, in which Māori communities are reliant on proprietary AI platforms governed offshore.

Such dependency echoes historical forms of economic colonisation. It positions Māori as consumers of imported intelligence rather than co-creators of culturally aligned digital systems.

Ethical and Spiritual Dimensions

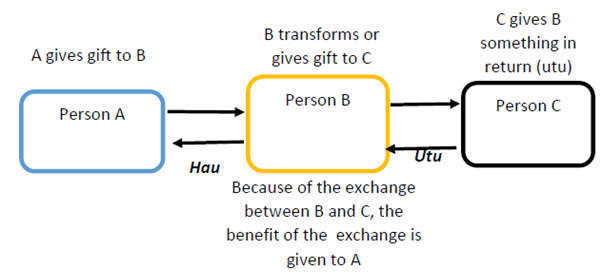

From a tikanga perspective, AI systems possess relational and ethical obligations. The reproduction of ancestral imagery, or reo fragments by generative agents will constitute breaches of tapu, compromising mauri and inviting makutu (spiritual imbalance). Western AI ethics lacks a framework to address such relational harms. Māori ethics, however, grounded in kaitiakitanga (guardianship), hara (violation of a tapu), and manaakitanga (reciprocity) as well as many others, offers a pathway for moral accountability within AI design and deployment.

Tiriti-Based Governance and Mitigation

A Tiriti-anchored approach to AI governance must affirm Māori authority and integrate Indigenous ethics into technical standards. Key mechanisms include:

- 1. Embedding Māori governance in all AI lifecycle stages

- Establishing Māori AI Ethics committees and a national commission with powers of audit and veto.

- Implementing Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) protocols for Māori data use.

- Developing Sovereign AI Infrastructure with controlled compute environments ensuring jurisdictional integrity.

- Integrating Tikanga-based auditing frameworks that assess systems tikanga compliance.

Such measures translate Te Tiriti o Waitangi into a living governance instrument for AI.

Conclusion

AI agents present profound challenges to mana motuhake and cultural survival. Without Te Tiriti based governance, they risk reproducing colonial hierarchies under the guise of innovation. Māori Data Governance Models and related frameworks offer pathways to assert mana motuhake and protect digital taonga.

True technological sovereignty will require Māori leadership not only in policy and ethics but also in engineering, design, and ownership. Only through Māori led governance can AI serve collective wellbeing, rather than perpetuating digital forms of colonisation.