The word Pākehā is a controversial word for some people. Some Māori and non Māori claim that the word Pākehā is offensive. Others have attempted to explain the word based on their own understandings and sometimes own hapū and whānau interpretations.

Introduction

This article provides an holistic analysis based on research from the early 18th century by scholars, native speakers, ethnographers and publications to some modern day research.

The motivation for this article was reignited when a Māori influencer on the popular social media platform TikTok stated that Pākehā is an original term for a flea. This has resulted in a multitude of rebuttals, debates and even threats of violence and other offensive statements. Regardless, no one has produced an holistic view based on un bias research and facts.

The term Pākehā was first recorded as being used by the Ngapuhi after some twenty years of contact with seamen; it was noted by Nicholas but omitted from the vocabulary of Kendall’s First Book; that it had reached the east coast, on d’Urville’s evidence, by 1827.

Historically, linguists and ethnographers have identified six possible origins of the word “Pākehā” to describe non Māori who are typically white Europeans. The term Pākehā is sometimes now applied to any non Māori person.

Black American whalers were historically called “Tangata Mangu” and French people “Tangata Wiwi”. This raises another issue about the term ‘tauiwi’ to describe foreigners and the modern term ‘tangata tiriti’ which both deserve further explanation, consideration and comparison to the meaning of the word ‘Māori’. I may do this in another post at a future time.

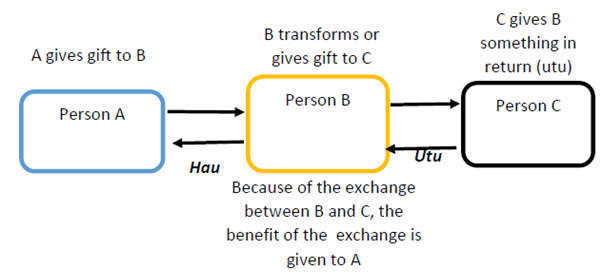

It is important to consider that at the time of the first whalers, Māori traded with and generally had good relationships with the whalers and that there was no land confiscations or Treaties. In fact, there was a lot of partnerships (commercial and personal) between Māori and the recent immigrants. Also, the fact that these early immigrants who spoke Māori, also referred to themselves as Pākehā, is likely something that they would not have done if the word at that time was derogatory.

As we know, the early missionaries who were responsible for documenting and creating a written form of the Māori language were dominantly associated with, therefore used the dialect and language of Ngā Puhi which has become standardised modern day Māori.

Due to colonisation and the inter generational substandard treatment of Māori by non Māori, the Tohunga Suppression Act, Native Schools, Urban Drift, Hunn Report, equality issues, racism as described in (Bartholomew and Ringer 2020), etc., it is likely that the meaning of the word Pākehā did evolve a little in some areas and with some whānau and hapū to include detrimental meanings. This theory could explain why research by Spoonley, P. (1991) states the term Pākehā seldom appeared in the 1950s and 1960s and it was not until the 1970s that this term related to a specific cultural group.

Epistemology

Below, I comment on the six common suggestions for the epistemology of the word Pākehā:

- Pakehakeha, one of the “Atua (gods) of the sea”.

According to Hoani Nahe (1894), the word Pākehā is derived from the “gods of the sea,” called Pakehakeha (also known as: Atua, Tupua, Pakehakeha, Marakihau and Taewa). They had an appearance like men, and sometimes even fish but had pale coloured skin.

- Pakepakeha

Many linguists and Māori language experts extrapolate that the term Pākehā is derived from the term Pakepakeha which is an alternative word for the more common term Patupaiarehe; a term applied to a race of people, some say mythical race who had pale skin and lived in the forests and only came out at nights and in the mist. They were known to kidnap Māori who ventured into the forests and hills by themselves.

- From the Hebrew adjective kehah

Kehah meaning pale or dim, in conjunction with the Maori causative pa. I find this theory highly unlikely and not worth of further discussion.

- Keha, a flea

Considering the pre colonial Māori language usage that Māori called a number of things that were introduced by an Iwi or person, or which had similarities to a person or group, by the same name; Māori often referred to the common flea as Pākehā as it was introduced to New Zealand by Europeans, together with the causative pa.

The term Pākehā was also used to describe some things that were brought by non Māori including the Pig, Turnip and some varieties of Kūmara and Potato all of which had light or white skin.

Some have stated that the origin of Pākehā has its origins with the terms paki, to slap, and keha, a flea. There is little proof of this concept.

- Poaka, a pig

As with the term ‘keha’ considering the pre colonial Māori language usage that Māori called a number of things that were introduced by an Iwi or person, or which had similarities to a person or group, by the same name. Māori often referred to the pig as Pākehā as it was introduced to New Zealand by Europeans. It is important to note that pork is considered a delicacy by many Māori and the term is not a derogatory term for Maori.

The term Pākehā was also used to describe some things that were brought by non Māori including the Flea, Turnip and some varieties of Kūmara and Potato all of which had light or white skin.

- From the expression “bugger you!”

A transliteration of the word ‘bugger’, a word said to have been described by Dr. Johnson (though not in his dictionary), a “a term of endearment amongst sailors”.’ It would be natural that Māori who often heard this term of address, then use it as a term to describe Pākehā.

Other terms for an European; a white man.

Each iwi and hapū have their own dialects and words (mita). There is research that states, and it would be logical that different terms were used in different areas for these new immigrants.

In the South Island, the first European setllers were referred to as descendants of Rapuwai “Ngā Aitanga a Rapuwai” and then later all non Māori were referred to by the term “Takata Pora” which translates as “boat people”. There were other terms for mixed racial people that would be considered derogatory and in contradiction to legislation that identifies who Māori are. This is important to note when considering the origins of the word “Pākehā”. The way that pre colonised Māori thought and the rich poetic language full of personifications and lore to describe things as opposed to the modern way of speaking Māori that has become normalised today.

Below is a list of some of the terms for non Māori white immigrants prior to the word Pākehā being commonly used:

- Atua

- Iouropi (Transliteration for European)

- Kaipuke

- Maitai

- Marakihau

- Piharoa

- Taewa

- Takata Pora (Ngāi Tahu)

- Tangata ma

- Tangata Moana

- Tangata Tupua

- Tupua

- Urekihau

Conclusion

The term Pākehā was not created as an offensive or derogatory word though some people based on life experiences may have adapted (in isolation) meanings of the word Pākehā.

It is most likely that the term Pākehā was applied to the sailors and whalers who visited the Bay of Islands by Ngapuhi who were imitating the common among the sailors themselves expression of “Bugger ya”. Considering the early missionaries and ethnographers avoided the term “Bugger ya” as it was seen as profanity and not a word that a gentleman would use, nor was it even written in full, that this is the most likely reason that the history of the word has been lost and debated so much over the decades.

Also that the term Pākehā was derived from the term Pakehakeha and the use of the sailors profanity would likely reinforce the matter that they were Pākehā.

References and other sources considered

- S. Atkinson (1892). What is a Tangata Maori. Volume 1, pages 133-135 of Journal of the Polynesian Society.

Ausubel, D. (1960). The Fern and the Tiki – An American View of New Zealand National Character, Social Attitudes, and Race Relations. London:Angus & Robertson (Publishers) Ltd.

Bartholomew, R. E. and J. B. Ringer (2020). No Māori allowed: New Zealand’s forgotten history of racial segregation : how a generation of Māori children perished in the fields of Pukekohe. Auckland, Robert E. Bartholomew.

Biggs, B. (1988). The word ‘pakeha’ : where it comes from, what it means. Te Iwi O Aotearoa.

Bohan, E. (1997). New Zealand – The story so far : A short history. Auckland:Harper Collins Publishers New Zealand Ltd.

Biggs, B. (1990). English – Maori : Maori – English Dictionary. Auckland :University Press.

Forsyth, H (2018) An identity as Pākehā. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1177180117752479

Hoani Nahe (1894) The origin of the words ‘Pakeha’ and ‘Kaipuke’ Volume 3, No.4, pages 235-236 Journal of the Polynesian Society

Immigrants and Ethnic Minorities – What words should I use?, (IM6/P231/6000/1985), Immigration Division Department of Labour, Prepared by the Resettlement Unit for the Interdepartmental Committee on Resettlement.

King, M. (1985). Being Pakeha. Auckland:Hoder & Stoughton Ltd.

King, M. (1999). Being Pakeha Now. Auckland:Penguin Books (NZ) Ltd.

O’Connor, M. (1990). An Immigrant Nation. Heinman Education [Social Studies].

Ranford, J Pakeha, its origins and meaning by. https://maorinews.com/writings/papers/other/pakeha.htm

Sidney J. Baker (1945). Origins of the words Pakeha and Maori, Volume 54, No. 4, pages 223-231 of Journal of the Polynesian Societyh

Spoonley, P. (1991). Pakeha ethnicity: A response to Maori Sovereignty. In Spoonley, P., Pearson, D., MacPherson, C. (Eds.), Nga take: Ethnic relations and racism in Aotearoa/New Zealand (pp. 154–170). Palmerston North, New Zealand: Dunmore Press.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.