Using paid, proprietary AI subscription services to build reo Māori and mātauranga models introduces serious risks of cultural appropriation, loss of control, and contested ownership.

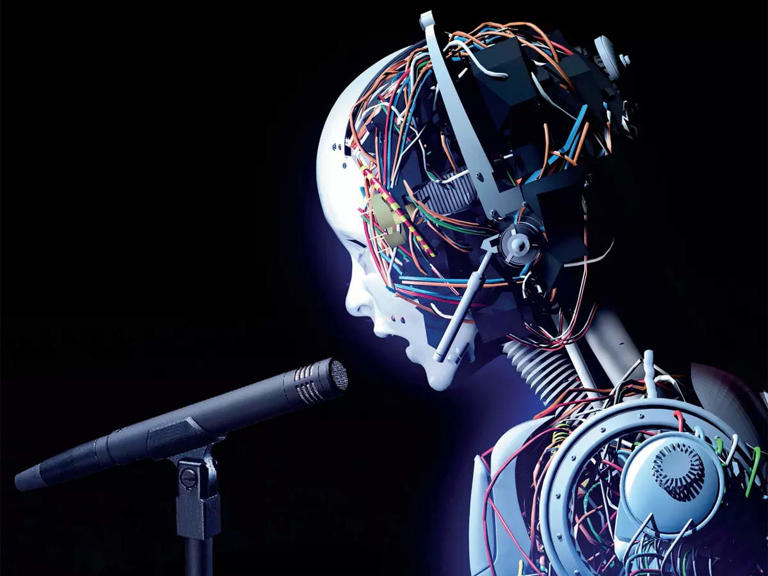

Māori have always been quick to adopt and adapt new technologies. Much of our traditional knowledge is only now being recognised as innovative within contemporary scientific fields. So when ChatGPT and other AI tools appeared, it was natural that Māori communities began experimenting with them. We now see a range of custom large language models (LLMs) drawing on ChatGPT and other AI platforms, promoted as bespoke reo and mātauranga tools.

I have tested four custom mātauranga and reo Māori LLMs created by Māori. Two of them included Māori Data Sovereignty disclaimers and encouraged users to double-check outputs. All four, however, produced serious hallucinations that could easily mislead people who are not experts.

Most of these systems used the OpenAI ChatGPT stack to create their models. That means all the sacred mātauranga being uploaded and used is stored on servers in the United States, on infrastructure owned and controlled by US companies. As a result, that mātauranga is subject to the US CLOUD Act and other foreign laws, as well as internal company policies and privacy settings. We already know that some of these policies explicitly allow staff to audit data, and that certain employees outside your organisation may have access under defined conditions.

One of the AIs I tested was trained on Waitangi Tribunal reports. Marketed as an “expert” on Tribunal material, it confused Dr Hana O’Regan and Sir Tipene O’Regan, partially merging their identities. It also claimed that the Ngāi Tahu takiwā extended up towards Picton and partway along the East Coast of the North Island, instead of the recognised boundary past Kaikōura. The same system was confused about marae pepeha and stitched together mātauranga from across the motu, creating entirely false narratives.

Another AI, designed to support cultural learning and te reo Māori, provided incorrect information about one of my marae, Koukourarata. It stated:

“The marae is named after Koukourarata, the ancestral bay – itself a transliteration or adaptation of the name ‘Cook’s River’, given by Māori to commemorate early interactions with European navigators. Iwi: Primarily Ngāi Tahu, with strong affiliations to Ngāti Huikai.”

There is no “Cook’s River” in the area. The name Koukourarata comes from a stream and refers to an historical moment in the hapū migration. Ngāti Huikai is a hapū of Ngāi Tahu, not a separate iwi.

The same AI, when asked about Māori leaders in reo Māori and AI, produced an answer about “Dr Anaru Keegan” while actually listing the work of Dr Te Taka Keegan.

A different AI, when I asked who I was, hallucinated that I am a female academic working at Te Whare Wānanga o Awanuiārangi, with whakapapa to Ngāi Tūhoe and Ngāti Awa. This appears to be a combination of poor training on Māori names (perhaps guessing from something like “Katrina”), partial knowledge that I studied at Awanuiārangi, and confusion with my supervisor’s name Taiarahia, which it treated as similar to my surname.

There are three key lessons in all of this:

1. Paying for a subscription does not protect your mātauranga. Once uploaded, it is no longer solely under your control and becomes subject to foreign laws, corporate ownership claims, and platform risk.

2. Even if current terms say that only certain staff under limited conditions can access your data, these are internal company policies that can be changed at any time without Māori consent.

3. Any medium to large organisation that takes privacy, sovereignty, and IP seriously is likely to see these arrangements as too risky in terms of data control, cultural safety, and long-term ownership of Māori knowledge.