This is an extraction of Chapter 6 from Tikanga Tawhito: Tikanga Hou Kaitiaki Guidelines for DNA Research, Storage and Seed Banks with Taonga Materials.

Introduction

Applying Māori knowledge to western concepts is to alter concepts so as to make it fit in with the local culture. Pre-colonial Māori knowledge was shared through many different mediums, such as pūrākau (stories), karakia (prayer), waiata (song), and “inscribed into whakairo (carvings) and raranga (woven patterns), that adorned waka (canoe), wharenui (meeting houses) and kākahu (clothes). Tā moko (tattoo) was a method of etching whakapapa (genealogy) directly onto the face of the wearer. In doing so, a face etched with tā moko expressed the story of the wearer’s life, their whakapapa, accomplishments, and triumphs as well as their status within their hapū” (Deana Walker, 2019). In the same manner as Māori shared knowledge pre-colonial times and now, this section will identify three Māori concepts to describe genetics and genomics.

Ruatau

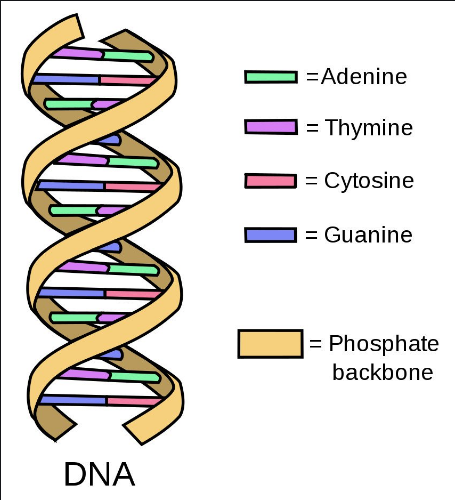

The interwoven form of the DNA structure is well known today. Double helix is the description of the structure of a DNA molecule. A DNA molecule consists of two strands that wind around each other like a twisted ladder. Each strand has a backbone made of alternating groups of sugar (deoxyribose) and phosphate groups. Attached to each sugar is one of four bases: adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), or thymine (T). The two strands are held together by bonds between the bases, adenine forming a base pair with thymine, and cytosine forming a base pair with guanine.

WAI 262 Claimant witness Mana Cracknell spoke of te ruatau, a dual helix formation, sometimes seen in kōwhaiwhai patterns, that represents the interwoven nature of different forms of knowledge (Waitangi Tribunal, 2011b, p. 80). The ruatau in weaving is the symbolic symbol of the atua Ruatau. In traditional knowledge among some Iwi, Rehua and Ruatau are two of the twelve whatukura or male attendants in the Māori spirit worlds. There were also twelve female attendants called Māreikura. The whatukura were messengers of Io, while the Māreikura greet the dead spirits when they enter the home of Io in the 12th spirit world known as Tikitiki-o-rangi.

Their home is called Te Rauroha. On another occasion they were sent by Io to see which of children of Ranginui and Papatūānuku would be worthy of the three baskets of knowledge. They chose Tane Māhuta the creator of humans and many other species of the forest. Whakamoeariki was the name of the house where dwelt the gods Ruatau, Aitu-pawa, Rehua, and the Pono-aua, called ‘The Many of Pono-aua (Best, 1924a, p. 36).

In an ancient karakia highlighting the relationship of ira atua and ira tangata recited during a person receiving their moko, a reference is made to Ruatau. “From Io knowledge is passed through Ruatau.” This descent from Io to Ruatau and finally to Tane-te-waiora describes how knowledge was passed down from the spirit worlds to the latter, who ultimately passed it on to humans.

Variations of Tane’s name which includes Tane-te-waiora indicating “life, prosperity, welfare, sunlight”, an appropriate term during the process of tā moko (King, M. 1973, pp. 20-22). DNA represents the relationship between the physical and the spiritual, a connection to all ancestors and atua since the beginning of time as does Ruatau.

Common DNA images are a metaphoric symbol of our human whakapapa. Our human chromosomes and genes determine our genetic makeup of individual existence. The molecule is packaged as a double stranded structure that is twisted into a helix. Similarly, the whiri whenu resembles a helix shape. They are physical manifestations of esoteric knowledge from our ancient past brought to life by the art forms of raranga and whatu muka, and all of the knowledge contained within these. This symbol is not unlike the process of miro (spin or roll together), which combines two strands of harakeke and forms a whiri (Taituha, 2014).

Whenu is a single-pair twining’ weaving technique which can be likened to Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid or DNA symbolised by the helix shape, because the living entities; each has an individual whakapapa and are unique because they are individually conceptualized and therefore carry their own story.

Wharenui as a genome

An original WAI 262 claimant Del Wihongi of the Ngā Puhi tribe stated a genome is a representation of a wharenui (Wihongi, H., 2019). This section analyses and extrapolates that statement, providing a Māori account of how a wharenui represents a genome.

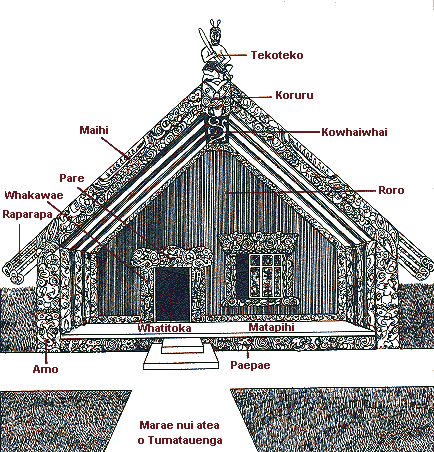

A wharenui has many names, including tipuna whare, whare tipuna, meeting house, marae, etc. In nearly all cases the wharenui proper is not only named after an ancestor but is a physical representation of the tribal ancestor it is named after and resembles the human body in structure.

There is a tendency to use the word ‘marae’ to mean the total complex of buildings and land. In fact, the marae is the open grassed or concrete space immediately in front of the ancestral meeting house. It is correct to use the word marae in either context, but the different meanings should be kept in mind (Richardson et al., 1988).

To comprehend the dynamics involved in maintaining a Māori tribal identity within New Zealand, it is important to understand the most central of all Māori institutions is the marae. It is a physically bounded three-dimensional space, capable of spiritually joining Papatūānuku (land) with Ranginui (sky) into which ira tangata may enter and commune with ira atua (the divine ancestors) (Tapsell, 2002).

The floor of the wharenui represents Papatūānuku, while the roof represents her husband, Ranginui. Tāne Māhuta, who separated the two, is metaphorically represented by the building as the poles that separate the roof and floor. The same representation of a DNA molecule. The two sides of the Phosphate backbone represent Ranginui and Papatūānuku, while the ATCG is a representation of Tāne Māhuta and the separation.

The sacred courtyard in front of a meeting house is Te Maraenui-atea-o-Tūmatauenga – the marae ātea is the domain of Tūmatauenga the Atua of war.

Before entering the wharenui, guests enter into an encounter situation, where challenges are met, and issues are debated on the marae ātea. Speeches and discussions that take place on the marae ātea are allowed to be forceful, representing the nature of Tūmatauenga.

The wharenui is the domain of Rongo, the Atua of peace. Speeches that take place within the wharenui are expected to be more conciliatory. The marae atea is the place where issues about genomic research and data storage, debates and the intentions of the researcher should occur. This allows for full and frank discussions as part of the Full, Prior and Informed Consent process.

DNA Strand. Source https://www.pngitem.com/

The associated wharenui and other prominently named buildings and structures of the marae further reinforce both individual and kin group identity in relation to outsiders by physically representing ancestors to which all members of the marae community genealogically trace their origins.

Consequently, the marae can be interpreted as a dynamic, Māori-ordered, metaphysical space, embracing the fundamental kin-based values of whakapapa (genealogical ordering of the universe according to mana descent and whanaungatanga kinship) and tikanga (the lore of the ancestors maintained by senior elders), where rights of access, especially in times of ritual, continue to be proscribed or prescribed solely by kin leaders. The marae is a living genealogical connection. The very essence of Māori genealogical identity to both the individual, whānau, hapū, iwi, present past and in the future. A DNA is interpreted the same way as explored within this research.

While turangawaewae is used to refer to the people who belong to a place, or the host people, it is also used to refer to the marae, a locale with deeply embedded identity. “The marae is the succession of things Māori from generation to generation” (Awatere & Dewes, 1969, p. 1). Turangawaewae applies to a shared or collective hapū or tribal identity and of belonging within a recognised geographic region (Rewi, 2010b, pp. 38-39). “Turangawaewae is the identity base of its people” (Tauroa, 1989, p. 11).

DNA is a biological form of a turangawaewae that is embedded within all Taonga Species. It is the identity of a place that is from generation to generation discretely succeeded into descendants. A donor who provides the sample is also referred to as the turangawaewae.

The tekoteko (carved figure) at the apex of the barge boards represents a renowned ancestor and represents the head. DNA is a biological material representing a shared identity from a whānau, hapū and Iwi tracing back to the original tipuna.

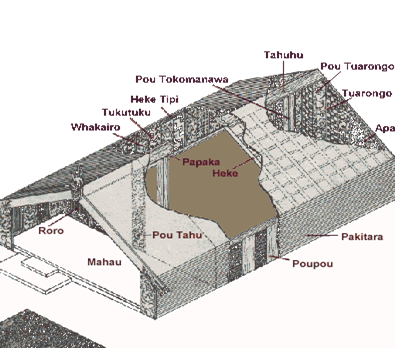

The maihi or mahua (front barge boards) angled down towards the ground represents the arms held out in welcome to visitors. The amo are short boards at the front of the wharenui representing legs, while the tāhuhu (ridge pole), a large beam running down the length of the roof, represents the spine.

The heke (rafters), reaching from the tāhuhu to the poupou (carved figures) around the walls, represent the ribs. Phosphate backbone is the DNA representation of the maihi.

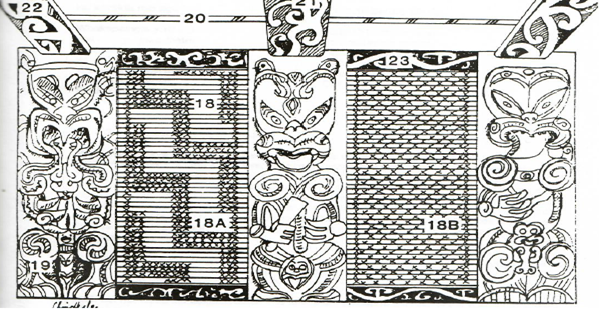

Inside, the horizontal ridge pole that runs through the centre of the building is seen as the backbone and the rafters are sometimes painted with kōwhaiwhai reaching down from the central ridge to the carved figures around the walls (poupou) representing the ribs.

The carved poupou represent an ancestor or relationships the people of the whare have with other people whilst sheltered inside the body of their tipuna.

Some people choose to rub noses with the pou, the same way that warriors rub noses with their taiaha (weapon) or a waka (canoe) as it is like greeting an ancestor and reiterates that idea that there is this living presence in every object, their mauri.

Connecting each carved poupou (top and bottom) is the papaka, a narrow panel usually decorated with kōwhaiwhai (See 23 in Figure 9). Significantly this represents the mauri (life force) and it goes right around the house (Richardson et al., 1988). Art in meeting houses always relate to particular ancestors and their stories (Mead, 1997, p. 163). A survey of a hundred years of tribal carvings, revealed a sophisticated intergenerational negotiation of internal and external cultural knowledge (Ellis & Robertson, 2016).

The Pou or carved poles represent the Base Pair: guanine, cytosine, adenine, and thymine. The Pakitara or side walls represent the Sugar phosphate backbone.

On the wharenui, we put up photographs of the ancestor who has passed on. The back wall in particular called a Tuarongo, but often all of the walls have photos of the deceased. We know photos are not the person, but they can become the person. It is the memory of that person being kept alive. A part of their mauri becomes a part of the back wall.

As our DNA is passed from generation to generation, so too is a part of the mauri of the deceased. It serves to remind us of we are and where we come from. The inheritance of DNA from generations to generations is symbolic of the wall of a marae.

Wharenui sourced from

Whare. Source Te Ara The Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Inside the Whare Tipuna (Richardson et al., 1988)

All of the physical attributes of a wharenui encapsulate the general attributes of a genome.

Māori DNA as whenua

All Indigenous Peoples around the world have emotional, spiritual, genealogical, and lived experiences to their lands and natural resources that co-exist with the land. All Indigenous Peoples have had their lands and natural resources confiscated by settler colonial military and governments resulting in their inalienable rights to the natural resources being abolished.

Māori biological materials/Māori genetic data is no different. The unique stage of this colonial evolution that Māori are presently at, is still in the early stages of significant exploitation and abuse of their genetic data, compared to other Indigenous Peoples such as the First Nations and Native Americans who due to their unique DNA markers, are being exploited by commercial research and scientists.

Unlike Māori DNA at this stage, “the blood of Māori, understood as storehouses of unique genetic diversity due to their presumed long physical and cultural isolation, is highly sought after, and to be collected quickly” (TallBear, K. 2013). Many Māori whānau, hapū and Iwi have been producing biracial children with colonial settlers for centuries. In a similar manner, native forests that once attracted other Taonga Species such as birds, insects, fungi etc., were quickly replaced much of New Zealand’s native forests, and in turn the Māori eco systems which caused the extinction of many Taonga Species and Māori knowledge of them.

Ngāi Tahu had its first contact with Pākehā sealers and whalers from around 1795 (57 generations). By the 1830s Ngāi Tahu had built up a thriving industry supplying whaling ships with provisions such as pigs, potatoes, wheat and many Ngāi Tahu women married whalers. This may account for one reason a significant Māori bio maker has yet to be found. Once a Māori bio marker is found, it is probable that commercial exploitation of Māori DNA will occur as it has with other Indigenous Peoples. The exploitation will likely be justified by the government as a means to address health equities, in the same manner that confiscated land was justified to socially, and economically, serve the nation as an agricultural country with land that was not apparently of any value or owned by anyone.

The colonisation and interbreeding did not occur with all tribes at the same scale, the same way as the development of Māori land did not occur everywhere in the country, despite being confiscated. This creates future issues and potential for exploitation of specific tribes such as Tūhoe who were least likely to have been colonised and interbred with the colonizer. There is a hypothetical possibility that these Māori tribes who were least likely to have interbred with Pākehā may have a unique bio marker. Land that was not colonised, has many Taonga Species including rare and near extinct species that also include many other species that are still being re identified.

Māori are in the pre-1830’s DNA ownership stage of our physical New Zealand history. Before the Māori land wars, Māori had deep emotional, whakapapa ties to the land and the environment and nurtured it in communal ownership to keep it in perpetual safety. In traditional Māori society, land and natural resources are held collectively by families and tribes for the next generation to avoid loss of land. It is acknowledged that the people are merely the kaitiaki of the land, unlike the commercial exploitation, disregard of cultural values and the destruction of land and natural resources by the colonisers. Present day researchers act in the same way, they assume ownership of samples and Māori genetic data.

The “right to gift access to one’s own body or bodily specimens on the individual is a notion that is rooted in Western bioethics but is culturally incongruent with Indigenous group or communitarian ethics” (Tsosie, Yracheta, Kolopenuk, & Geary, 2021). Māori genetic data that is provided to researchers must follow the same principles as land using intergenerational stewardship (kaitiaki). “Indigenous-derived samples and data accepted for research should be considered the continued property of the donor/community involved; hence DNA is considered “on loan” (Arbour & Cook, 2006) to the researcher as opposed to being a gift (Tsosie et al., 2021). By only loaning biological samples to researchers, as Māori do with land when they lease or rent land, then the potential to participate in the genetic economy is greater, but the risk of having their identities misrecognized, commodified, and sold as ancestry tests will still exist (Fox, K., 2020).

Māori DNA Evolution of bio piracy and Sovereignty.

| Phase | Historical moment in NZ history | Task |

| Phase 1 | The Colonial settler period to the Māori Land wars and land confiscations of the 1860’s. | Prove DNA is a Taonga and seek Tikanga Sovereignty (this research). |

| Phase 2 | 1860’s when Māori had to identify their whakapapa to the Crown and prove title to their own native lands.

|

Rely heavily on International Indigenous Peoples experiences with bio commercialisation of gene research. Comparing and proving colonisation, imperialism, bio prospecting, bio colonialism, bio commercialisation of Taonga |

| Phase 3 | 1975 when the Waitangi Tribunal Act was introduced.

Modern era of Waitangi Tribunal claims and repatriations. |

Taking breaches of Te Tiriti with Māori genetic data to the Tribunal and seek redress. |

Māori DNA Evolution of bio piracy and Sovereignty

Many Indigenous Peoples have already lost much of their sovereignty with genetic data and research outcomes with commercial, ownership exploitation and bio prospecting. This is Phase 1 of the Māori DNA Evolution.

Māori have a small window of opportunity in phase 1 to prove traditional value of their genetic data and prove that it is a taonga as Māori do with land. This research has already highlighted that for Taonga Species that it may be too late for many, but there is still myriad of Taonga Species that have not been bio pirated to date despite it currently being an academic normal practice to sequence and share the genome in online repositories.

The Second stage for Māori is to prove their identity and indigeneity as occurred in the Māori Land Courts. If Māori are unfortunate to get to stage 2 of this evolution, then Māori will need to rely heavily on the international community of Indigenous arguments.

Unlike other Indigenous Peoples, Māori have the binding treaty obligation of the Crown to the right of protection of Taonga with Te Tiriti. Before stage 3 is considered, wider understanding of traditional tikanga and traditional knowledge and an acceptance of a definition of Taonga Species is required.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.