A Law Foundation-funded report Digital Threats to Democracy, one of the most in-depth reports published locally to date on the negative side effects accompanying the rise of digital media. The report also considers Māori and Indigenous democratic issues. Again, the first time this has occurred.

I have extracted key Māori views from the report which is 246 pages. The whole report should be read for a better oversight to the bigger issues.

Online abuse, harassment and hate – particularly of women, people of colour, queer people, people with disabilities and people from minority religions – undermines democratic participation not only online, but offline (pg 13).

I am concerned of the use “people of colour” in New Zealand as it detracts away from Māori and Indigenous Peoples. We are not all “people of colour”.

The opportunities for digital media are significant and important. If used well, digital media can enable governments to respond effectively to the experiences of marginalised groups, to ensure equitable policies and practices are designed, delivered and adjusted, and to build trust in the democratic institution as responding to the needs of all people. (Pg 15)

The seven key threats we identified to inclusive democracy from digital media were: the increasing power of private platforms, foreign government interference in democratic processes, surveillance and data protection issues, fake news, misinformation and disinformation, filter bubbles and echo chambers, hate speech and trolling, and distrust/ dissatisfaction with democracy. (Pg 16)

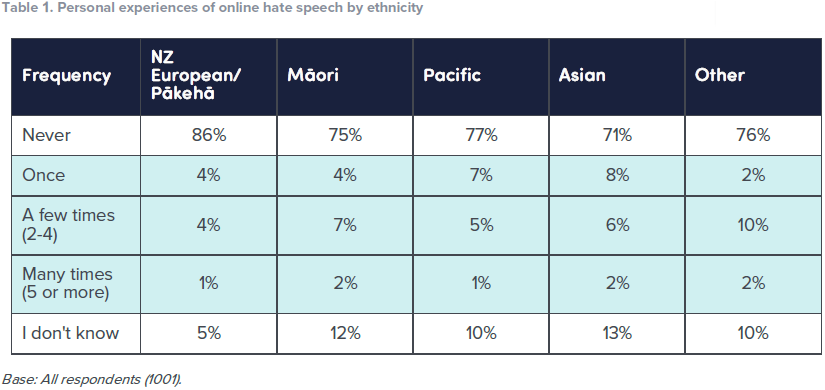

Statistically Māori, Pacific Islanders and Asians are more likely to suffer hate speech, harassment and trolling. Resources need to be given to these issues.

Taiuru asks whether Māori data and data relevant to Māori is being adequately protected

as a taonga in compliance with the Treaty. And whether Māori data sovereignty is being

enabled. One possible solution to this is an approach similar to that taken on the Solid

website (https://solid.mit.edu/). Another area where better protection is needed is in

online abuse, Taiuru says that Netsafe are not currently equipped to deal with tikanga

Māori issues online or even deal appropriately with Māori victims of online abuse. There

is a need for cultural and ethical considerations of te ao Māori in developing digital

security policy. Further discussion and protections are also needed around the digital

colonisation of Māori culture and values. Overall, says Taiuru, appropriate consultation

and engagement is needed by Netsafe and other organisations with a diverse range of

Māori around digital issues affecting Māori including cyber safety, online abuse, data

management. Pg 80 Background Report

NetSafe are severely under funded and lack an appropriate Māori voice via partnerships. We have already seen from the NetSafe conference in 2018 that NetSafe and Facebook were not resourced for online bullying of a minority language. Furthermore, a Treaty claim needs to be made in regards to online safety and to recognise Māori Data as a toanga. I think the rest of my quoted statements express my other thoughts.

Some interviewees argued that there was a role for New Zealand to play as a leader on indigenous data sovereignty and issues relating to Māori digital issues. This would first require us to address the significant gaps in our own protection of indigenous rights online. One of the most critical issues is the need to protect indigenous data sovereignty, allowing Māori ownership and control of Māori data. Pg 52

In addition to this, we need the New Zealand governing body who manage disputes of .nz domain names to recognise that their policy does not consider Māori rights, nor any consideration to the Treaty. The Domain Name Commissioner has an open consultation at the moment which I welcome and have contributed to here.

There was an interesting pattern of engagement reported by minority ethnic groups. Of those Māori, Pacific and Asian people who were in the survey, 28%, 34% and 31% respectively said they ‘Belong to a group on a social media platform that is involved in political or social issues, or that is working to advance a cause’ identified as “different identify”. This compares to 23% of NZ European/Pākehā people in the sample. Similarly greater proportions of Māori (32%), Pacific (43%) and Asian (28%) people ‘Follow any elected officials, candidates for office or other political figures on a social media platform’ than NZ European/Pākehā people (23%). Pg 127

Māori are so geographically diverse, that social media and Internet communications are the logical choice to interact and support common causes. It also removes the Marae/Iwi hireachy we have in Māori society. There are many examples online of people setting up groups and networks for causes. In the early 2000 period, we also witnessed Māori utilising services such as Yahoo Groups to support and discuss common causes. This is also likely due to a traditional lack of media coverage with all media.

Higher proportions of Māori and Pacific people in the survey used social media to encourage people to vote or take action on a political issues than NZ European/Pakeha people (31%, and 37%, compared to 22%). Greater proportions of younger people used social media to encourage voting compared to older people also. Pg 127

Many of our Māori politicians make themselves available via social media. Most also seem to be unavailable or severely limited once they are elected. In my opinion Marama Fox was the exception. When she was in parliament, she relentless used social media and was aware of people in her social media networks. Interestingly, iwi leaders do not appear to use social media, opting for traditional forms of engagement.

The next most common source of information were friends and family (63%). More younger people in the survey (around 60%) got information from friends and family on the issues than those over 65 (49%). There were also ethnic differences – 77% of Māori and 75% of Pacific people said they got information on the issue from friends and family, compared with 63% and 64% of NZ Europeans/Pākehā and Asian people. Pg 129

This is not surprising. This is merely reflective of our culture.

Former Māori Party MP Marama Fox found that the small number of seats held by her party in Parliament meant she had very limited opportunities to pose formal questions in the House, but social media gave her alternative channels to have her say on the issues of the day. “I was only able to ask one question every eight days, and two supplementary questions a week. So I had to sit there, filtered, and silent and muted, and that just pissed me off. So I would get on social media, and engage people there to get my say out there.” Pg 161

This is reflective of my observations of how Māori politicians use social media. As I said above, Marama Fox was the most engaged Māori politician with social media I have observed, even to this date.

Marama Fox insists that meeting face-to-face is still essential for politicians and for political discourse generally. “The keyboard warrior disappears and you’re more willing to have a calm conversation about something, rather than an argumentative one.” Fox also points out that the combative tone of much digital discussion of politics will put off some people, and specifically people from certain cultural backgrounds. “[Some] Māori, like my husband, hates me arguing around the kitchen table with my sons. Fox says that because she was educated in a Pākehā cultural context, she is more comfortable with that sort of confrontational discussion. “He calls it arguing. I call it a debate.” Pg 163

Any Māori politician would say the same thing that face to face is also important. It is a part of our culture.

Marama Fox pointed out, the risk of false information being digitally published and spread in the heat of an election could have a devastating effect on a candidate even if there was no suggestion of involvement by foreign state actors. “I remember one person who rang up to someone on our campaign and said “I’ve just been with Marama all night at the casino, the cops were after us, we just spent $10,000 of the Māori Party money, and we’ve blown it on the tables.’ She was just jack talk, but if she’d gone to my Facebook feed, and said that, in the two days leading up to the election. Anybody could do that, at any time, and that’s dangerous.” Pg 178

This is a common issue with Māori who read something online and believe it is true because it has been published online. Again, more cyber safety resources are required that tackle specifically Māori issues.

Erika Pearson argues, for example, that the platforms themselves ought to take a more proactive approach to countering this kind of abuse, but in a way that acknowledges and respects the experience and perspective of the people who are being targeted. This is particularly important, Karaitiana Taiuru has argued, when platforms or regulators are dealing with Māori victims of online abuse. Pg 182

The biggest issue here is “whakama” Māori being ashamed or too embarrassed to ask for help. Another example is iwi or ancestor taunts that look innocent to non Māori but are highly offensive in te ao Māori.

Thomas Beagle also sees particular threats from online abuse to participation in public debate by people from marginalised groups. Trolling has become, says Beagle, a tactic for driving people of the internet. “That’s a concern to me because being able to drive people off the net is a real threat to our freedom of expression. The net is where we’re having our political debate.” And the people being driven away by online abuse, he says, are the people who are already disadvantaged in some way. “Of course in our society, that means Māori voices, LGBT voices we’re pushing off. Women as well, some of the misogyny we’re seeing here is a real worry.” Pg 184

Looking at the comments section of Stuff about any Māori topic shows the racism and trolling. The online abuse is much worse in other discussion web sites.

Karaitiana Taiuru, PhD candidate at Te Whare Wananga o Awanuiarangi and long time advocate for Māori online rights, has also advocated for greater user control over personal data. He argues that Māori data; ’data that is held by Māori, made by Māori or contains any Māori content or association’ is a taonga under Article 2 of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, and should not be treated as a commodity product. The current approach to data taken by digital platform companies doesn’t account for indigenous rights, nor does it allow Māori adequate control or sovereignty over their own personal data and what it is used for. Pg 191

When our Māori and Iwi leaders understand better that Data is the new Land, then we may see more attention given to Māori data.

The UN Internet Governance Forum was established as a multi-stakeholder forum to discuss issues arising in relation to the governance of the internet. Carter says it hasn’t been as useful as some hoped at it’s foundation, but it at least is based on the principle of engaging a full range of stakeholders, including tech companies and civil society, in discussions.

For multi-stakeholder processes to produce results that would be in the interest of all stakeholders, they need not only to include a diverse range of stakeholders but also to ensure that there is some balance of power between the different parties. One idea that came up in a number of interviews was the need to strengthen the civil society arm of multi-stakeholder internet governance, and in particular to need to better represent the needs and interests of users of digital media. Marcin Betkier and Erika Pearson both suggested that more needed to be done to redress a massive imbalance of power in these processes, and particularly to restore more power to the voices and interests of internet users.

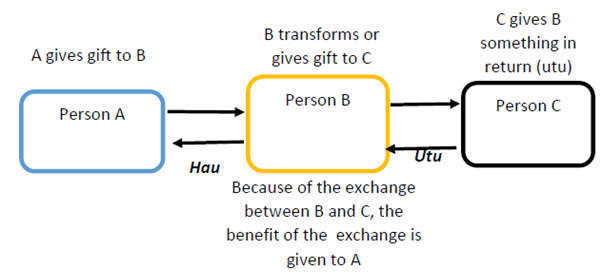

This would also include ensuring that the cultural needs of Māori in online spaces are upheld, and that Māori sovereignty over the taonga of data is incorporated into new governance structures and regulations. Karaitiana Taiuru has identified two core Māori values which would support an inclusive data system; manaakitanga, where data users demonstrate tolerance and respect, and kaitiakitanga where New Zealanders, collectively, become guardians of our data ensuring it is managed with integrity in a way which enhances personal mana, rather than eroding it. Pg 196-197

InternetNZ the New Zealand Internet governance group has also lacked a real Māori voice and representation for over the past 19 years that I have been involved with them. We have the Treaty of Waitangi, Māori language Act and a society that is becoming more comfortable with recognising Māori rights. The introduction of new GTLD’s by ICANN totally ignored the worlds Indigenous Peoples too. As good Internet citizens, it is time to consider gender and minorities.

Finally, but perhaps most importantly, some interviewees argued that there was a role for New Zealand to play as a leader on indigenous data sovereignty and issues relating to Māori digital issues. This would first require us to address the significant gaps in our own protection of indigenous rights online. Karaitiana Taiuru has outlined a range of areas where improvement is needed and has suggested some solutions. One of the most critical issues is the need to protect indigenous data sovereignty, allowing Māori ownership and control of Māori data.

Taiuru asks whether Māori data and data relevant to Māori is being adequately protected as a taonga in compliance with the Treaty. And whether Māori data sovereignty is being enabled. One possible solution to this is an approach similar to that taken on the Solid website (https://solid.mit.edu/). Another area where better protection is needed is in online abuse, Taiuru says that Netsafe are not currently equipped to deal with tikanga Māori issues online or even deal appropriately with Māori victims of online abuse. There is a need for cultural and ethical considerations of te ao Māori in developing digital security policy. Further discussion and protections are also needed around the digital colonisation of Māori culture and values. Overall, says Taiuru, appropriate consultation and engagement is needed by Netsafe and other organisations with a diverse range of Māori around digital issues affecting Māori including cyber safety, online abuse, data management. Pg 223

In New Zealand we have a sound basis to become international leaders. We just need to recognise the Treaty of Waitangi and incorporate kaupapa Māori frameworks and methodologies into new digital initiatives and Internet governance. New Zealand led the world with Indigenous Domain Names, so we are innovative and small enough as a country to do it.

Evidence suggests the internet has given minority groups greater access to similar voices, collective action and political actors, it has also exposed them to more hate and bigotry. In 2017, one in ten New Zealanders experienced hate speech online and three in ten encountered hateful content.3 One in three New Zealand women experienced online abuse and harassment. Of those women, three in four (75%) said they had not been able to sleep well, one in two (49%) feared for their physical safety and one in three (32%) feared for the physical safety of their families as a result.4 In 2018, one in three Māori (32%), and one in five Asian (22%) and Pacific (21%) people experienced racial abuse and harassment online. Pg 240

Again, more resourcing needs to be provided to combat these issues. Media sites and discussion sites need to consider what is free speech and what is hate speech and take action.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.