After generations of successful assimilation of Māori culture by governments including Native Schools, Tohunga Suppression Act, The Hunn Report, etc, many Māori were left without knowing their identity. There has been an increasing trend for those Māori individuals to reclaim back that knowledge.

For many people, they are disconnected from their families and communities, so using Artificial Intelligence (AI) has become a popular resource, in particular for learning pepeha.

A pepeha is far more than a personal introduction, it is an affirmation of whakapapa connecting a person to their mountain, river, hapū, iwi, atua, marae, whenua and ancestors, situating them within the living ecology of te ao Māori.

In recent years, digital tools including Artificial Intelligence (AI) have begun offering automated pepeha creation. While such tools appear convenient, their use raises deep epistemic and cultural concerns. Māori identity cannot be produced by probabilistic language models trained on incomplete and colonial datasets.

Māori should learn and express their pepeha through communicating with whānau and visits to their marae, touching and smelling their river, mountain, and other things that connect them to being Māori, not through AI.

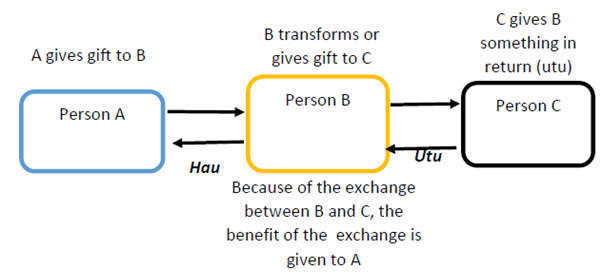

Reciting one’s pepeha is a performative act of connection, not a factual statement to simply be filled in. It is a taonga requiring authenticity and accuracy, not approximation or simulation. Any distortion of pepeha information risks distorting whakapapa relationships and eroding cultural integrity.

AI Hallucinations

AI systems particularly large language models generate text by predicting probable word sequences based on patterns in their training data. They do not know facts, they statistically infer them. This process can produce hallucinations: fabricated details presented as truth.

In a pepeha context, hallucinations might mean assigning the wrong iwi to a hapū, mismatching rivers and mountains, or fabricating ancestral names, as I will give real life examples of. Such errors are not minor inaccuracies, but they are violations of whakapapa, truth and of tikanga. A new form of digital colonialism that replicates early missionaries work to eradicate whakapapa of Māori male, female and mixed gender atua to a supreme western male god.

Unlike factual mistakes in other contexts, a pepeha error can carry social and spiritual consequences. A misplaced maunga or marae reference may unintentionally disrespect mana whenua, perpetuate colonially imposed boundaries, or misrepresent lineage ties.

Because AI lacks accountability and emotional understanding, it cannot exercise aroha or humility when engaging with such knowledge. These qualities are central to Māori modes of learning and speaking about whakapapa.

Another fundamental limitation of AI is its dependence on existing datasets. Most public training data are sourced from English language internet content dominated by Western epistemologies. Māori language and knowledge especially locally specific mātauranga about iwi, hapū, marae, and rohe are dramatically under represented.

Where Māori information does exist online, it is often fragmentary, outdated, or de-contextualised. Consequently, AI models are more likely to reproduce colonial narratives or generalised summaries rather than authentic local knowledge.

Mātauranga Māori are often restricted by tikanga that prohibit open use. Taonga such as histories, waiata, and oral traditions are not digitised because they are considered tapu. AI models trained without explicit consent risk breaching Te Tiriti and Tikanga principles.

AI may also conflate distinct identities, for example, confusing or misattributing hapū and Iwi affiliations such as Ngāti Kuri the iwi in the far north with the Ngāti Kuri hapū of Ngāi Tahu in Kaikoura, placing a sacred tribal mountain to another iwi. These distortions can perpetuate historical erasure, tribal conflicts and cause deep shame to the person who is reciting wrong pepeha, rather than revitalisation and acknowledgement of pepeha.

Even when AI systems are fine tuned on Māori material (even by Māori), they still lack cultural reasoning. A model might “know” that Wanganui is a river, but it does not understand its mauri, its legal personhood, or the metaphoric resonance in saying Ko au te awa – ko te awa ko au. Only humans grounded in whakapapa can embody that meaning. AI can also confuse Māori names, assigning Waikato awa status to Wanganui awa causing deep grievances for many.

If individuals bypass whānau, they lose opportunities to engage with oral history, pronunciation, dialect variation, and stories of place. These are not data points but experiences that transmit identity. Over reliance on digital tools can create shallow connections called algorithmic culture – knowledge consumed rather than lived.

There is also a danger of cultural homogenisation as AI systems generalise patterns, leading to “template” pepeha that erase regional distinctiveness. The unique rhythms of Tūhoe or Ngāi Tahu expressions could be flattened into standardised sentences, replaying historical outcomes in our colonial education and religious systems that once suppressed dialectal variation in te reo Māori.

AI tools often store user inputs in cloud infrastructures owned by multinational corporations. Entering personal or ancestral information into these systems raises privacy and sovereignty concerns. A pepeha, while shared publicly in certain contexts, remains intimate, its storage and possible reuse by foreign algorithms without consent is likely.

Visiting the marae, an individual can physically see the maunga, smell and feel the awa, and experience the environment that shape’s identity and turns abstract names into embodied memory. Such experiences cultivate mauri and mana that cannot be felt from a digital interface.

The process of researching pepeha within whānau networks can reignite connections among dispersed relatives. Many urban Māori who have lost contact with their marae rediscover kinship through these inquiries. AI cannot facilitate that reconnection; only human relationships can.

Conclusion

Digital tools can support learning when guided by tikanga Māori. For example, Māori controlled databases or language apps built under tikanga principles may assist pronunciation or provide verified maps, but the output must still be fact checked. Systems co-designed with Māori oversight can enhance learning, whereas general purpose AI trained on unverified global data undermines it.

Until large models are trained within Māori ethical frameworks with consent, accuracy, and Māori, hapū, Iwi, marae, hāpori validation, they should not be relied upon for pepeha, whakapapa or any mātauranga.

Pepeha is not an information field to populate, but a living declaration of whakapapa and belonging. AI systems are prone to hallucinations and founded on incomplete and biased training data. The AI cannot uphold the cultural precision or relational depth that pepeha demands.

To entrust such sacred knowledge to non Māori algorithms risks misrepresentation, cultural harm, and loss of sovereignty. True learning occurs through kōrero with whānau, standing on marae, and experiencing the landscapes that shape identity.

In choosing human connection over artificial convenience, Māori affirm the very essence of pepeha an interconnectedness of people to the whenua and ngā atua.